The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Custer’s Trail Today

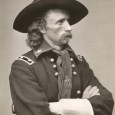

Landmark moments in American history include the arrival of the Mayflower, the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the Louisiana Purchase. For the Dakotas, a definitive moment was the Custer Expedition of 1874. That brief exploration of the Black Hills was a final chapter in western expansion and forever changed life on the plains.

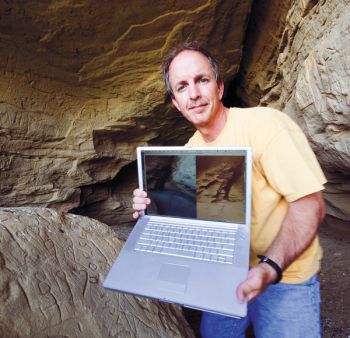

For nearly 15 years, photographer Paul Horsted has documented and photographed the Expedition route. In 2002, Horsted and co-author Ernie Grafe published Exploring with Custer: The 1874 Black Hills Expedition. The book focused on photo sites, the gold discovery and the Expedition trail within the Black Hills. Then in 2009, Horsted and Grafe, along with historian Jon Nelson, compiled Crossing the Plains with Custer, which follows the Expedition as it traveled from Fort Lincoln in North Dakota to the Black Hills, and the return trip just three weeks later.

That path across the plains has never been officially marked or explored since Custer’s journey. To find the correct passage, the authors started with a map drawn by the Expedition’s chief engineer, Col. William Ludlow. Horsted found the map, part of a rare copy of the official U.S. Government report of the 1874 Expedition, at a bookstore in Rapid City. After scanning the map, he used mapping software to make it transparent and placed it on top of a modern satellite image showing area landmarks. That made it possible to develop GPS coordinates for numerous places where modern roads and other public areas cross the trail used by Custer’s 110 wagons.

“We’ve found it to be remarkably accurate, considering the vast distances they covered,” Horsted says. The route to the Black Hills was 310 miles long, while a different return trail was 355 miles, according to Expedition documents. Both trails pass through the Cave Hills area of northwestern South Dakota.

The path, they discovered, is almost entirely on private land, so Horsted and Nelson knocked on over 50 doors to ask permission to investigate. One landowner was rancher and pilot Lex Burghduff, who has a 12,000-acre ranch near the Cave Hills. The authors deduced that the Expedition camped on his land July 11, 1874.

Burghduff was aware that his land holds rich history. “We’ve found pieces of old harnesses and some casings that were fired by the cavalry,” says Burghduff. “We find arrowheads on a daily basis.” A friend and local historian named Bob Kriege, who recently died, taught Burghduff much of the area’s history. Kriege said Native Americans would winter near the Cave Hills after summering in the Fort Pierre area. They were following game that spent winter months on the south and east side of the Hills.

Horsted is the first person to ask Burghduff for permission to explore his land because of the Expedition. Burghduff took him on a plane ride to look for ruts made by the Expedition’s wagons.

“What Paul is doing is preserving history. I think it’s just really something overlooked in schools. We weren’t taught local history,” Burghduff says. “I’ve got two boys, Hazer and Jake, and I show them pictures that Paul sends me and the artifacts we found. We hunt for arrowheads and beads and pottery. It could easily be forgotten.”

Once Horsted and his co-authors pinpointed where they thought a camp was, they were usually within about a mile’s range of the right spot. They used metal detectors to look for artifacts Custer’s men left behind to verify the accuracy of sites shown on the map.

“Metal detecting is a lot of work, but fun,” Horsted says. “We spent hundreds of hours in heat or snow trying to pursue this and you don’t just stop, you have to go until you have a breakthrough and find an artifact that you recognize from the era when the Expedition passed.

“There was a time when I thought it was fantastic to find a square nail,” he says, “but now I’ve found buttons, tin cans with lead seals that were used in that period of history, a nickel from 1867. The most exciting thing I found was a military type spur. But coins are great because they give us a solid date.”

Horsted, Nelson and Grafe are intrigued with the era. “I’m living in the Black Hills because of what happened at that point in history,” Horsted says. “I’m no big fan of Custer. We admire the way Custer led the expedition, because not anyone could have led it in a successful way, but that came at a cost to the Lakota and Cheyenne and other tribes.”

The official expedition photographer, William H. Illingworth, took abundant photos documenting the Black Hills. In his first book, Horsted re-photographed Illingworth’s photos. Some scenes looked identical, while others showed the dramatic development of the century — especially in the Rapid City area. Even within the last 10 years, Horsted has noticed changes. “There are entire places where homes have been built where there was an empty field just years before,” he notes.

Illingworth took only eight shots between the Hills and Fort Lincoln. Because Horsted didn’t have an abundance of photos to use for comparison, he relied heavily on journal entries, newspaper stories from the five journalists traveling with the group, and Ludlow’s official government report to guide him in photographing scenes Custer’s men encountered. Those first-hand accounts accompany Horsted’s photos in the book. “Day by day as they travel you can read what the newspapers say happened, then what an Army private said and he might have a completely different point of view from the officers who recorded the same event,” Horsted says.

Ernie Grafe’s role was to compile those accounts from all available sources. Originally from upstate New York, Grafe moved to the Black Hills 35 years ago. He immediately fell in love with the area and started learning the history. He researched Custer’s trail, started hiking it himself and met others with the same interest, including Horsted.

Despite Grafe’s extensive research for the first Custer book, he still ran into surprises while working on Crossing the Plains. One of the biggest, says Grafe, was finding that George Bird Grinnell, the Expedition’s paleontologist, uncovered a dinosaur bone just southwest of Buffalo. It was the first to be found in the Hell Creek formation, which since has produced several dinosaur discoveries, and perhaps the first dinosaur bone unearthed in Dakota Territory.

Written accounts of the trip are strikingly different on the way to the Black Hills compared to those written on the way home. As the Expedition travels to the Hills, the journals are full of anticipation and speculation about what will be found. On the way home, when the route crossed hundreds of square miles that had been burned off by prairie fire, there is less excitement and a real desire to reach their destination, especially when some of the soldiers are forced to start shooting their horses because of the lack of grazing available on the burned prairie.

“We get to tell the ‘rest of the story’ in Crossing the Plains,” says Horsted. “I’ve been really inspired photographing the places we know they passed through, standing on top of the same buttes they climbed, walking the same Badlands they crossed.”

By comparing Illingworth’s photos with Horsted’s, we can gauge both natural and manmade changes occurring in the last 135 years. Perhaps after another 100 years, Horsted’s photos will be used to gauge changes that lie ahead for the plains and the Black Hills.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2009 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments