The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Forbidden Culture

|

| A give-away event at a community on the Pine Ridge Reservation. |

A renaissance occurred in the 1960s on the Yankton Sioux and Rosebud reservations when tribal elders brought traditional beliefs out from underground and into open use for the first time since the 1890s. But how did the practices survive 70 years of suppression that preceded the renaissance?

I found answers to that question early in my career when I came to know Charles Kills Enemy and Joe Rockboy. Charlie and Joe didn’t know it, but they and their friends were cultural preservationists before the renaissance. Charlie grew up on the Yankton reservation with the name Jonas Chasing Crane because he was raised by his grandparents, Charles and Sarah Chasing Crane. Later he moved to the Rosebud and took the name of his father, Mark Kills Enemy. He became a ranch foreman and rode with cowboys at non-Indian rodeos — sometimes on horses and sometimes on buffalo.

He began his quest for spirituality in the hanbleceya, seeking contact with spirits. Over the years, he became an accomplished medicine man. He maintained his central lodge on the Rosebud Reservation in his old age, but his influence extended throughout the Sacred Pipe to relocated tribal members in California, Ohio and elsewhere.

|

| Joseph Rockboy sings a peyote song during a prayer meeting in the 1970s. At that time he was the oldest member of the Native American Church. |

Joe Rockboy was raised in a log cabin on the Yankton Reservation under the tutorial counsel of traditionalist “aunties” as well as his mother, a devout Episcopalian. She wanted Joe to be an Episcopal minister but during his teen years he discovered that ministers in the Episcopal Church must have a heritage of mixed-blood and Joe was a proud full-blood. He often declared himself 4/4ths Indian.

He left the Episcopal Church in 1917 and became an active participant in the Native American (Peyote) Church. Alcoholism plagued him in his early years. Women even hid vanilla extract from him in their kitchens. He rode in the 101 Wild West Show, but as a Mexican because the cast already included a sufficient number of Indians. He returned to the reservation in the 1930s, married and had a son.

On the reservation he worked on Indian New Deal projects, then drove a gravel truck to help construct the first runway on the airfield now known as Ellsworth near Rapid City. He also worked at a plant near Hanford, Wash., where the first atomic bomb was being produced.

Drinking encumbered his life until, in 1946, he nearly froze to death while under the influence. He never drank again.

Joe Rockboy worked in Chicago in the 1950s, but returned to the Yankton Reservation in the 1960s to hold a variety of jobs, including a cultural advisory position. He was an exemplary member of the Greenwood Chapter of the Native American Church and an organizer and participant in many aspects of the Indian renaissance.

Memories and stories from Charlie and Joe serve as bedrock information on the beliefs and practices that were preserved in relative isolation from 1890 to the 1960s. Lakotas and Yanktonais on their larger reservations in the United States experienced fewer obstructions to their cultural activities but on the Yankton and Rosebud reservations, traditionalists faced opposition from Christian missionaries and federal employees who believed in assimilation.

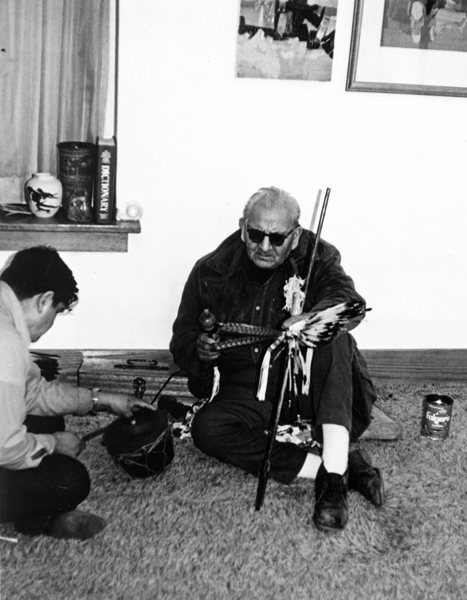

|

| Medicine man Charles Kills Enemy prepares a wanbli (eagle) lowanpi altar for a ceremony to summon spiritual assistance for someone in need. |

The Greenwood Native American Church endured in spite of efforts to suppress it from its inception. The stubborn members secured a charter from the Secretary of State in 1922 but still faced social pressure from non-Indians to abandon their native religion.

A belief system based around the Sacred Pipe encountered even more hardships. A network of dance halls became a protective environment for ancient tribal legacies. The halls should not be confused with the type in which Lawrence Welk began his band career. Drums were the norm, not accordions, and dancers didn’t do the polka.

Sketchy histories of the dance halls appear in written records around the turn of the 20th century — in isolation from both agency and mission influences. Traditionalists founded and managed the halls to nurture their legacy of dance, music, give-aways and other social practices, as well as recreational activities such as games and horse races.

Each Dance Hall Chief managed his hall from an adjacent, government-issued house. Joe Rockboy remembered the halls with great fondness when we became friends in the 1970s. “At one time we had seven dance halls,” he told me. “They was big square buildings about 36 feet by about 70 feet, I’d say. Our people put them up at their own expense. They all worked on building the halls.

“In the Thirties, some of our people had a real hard time, lost their horses and had no way to haul firewood,” he said, “so they tore most of the halls down and used the lumber for firewood, I think.”

Joe particularly remembered the Old Hay Hall northeast of Greenwood. A man named Wooden Nose was the Dance Hall Chief and drum keeper. “When there was going to be a dance, he’d go down to the agency, tell the agent that there was a dance arranged, and the agent would issue a slip that it was all right,” Joe told me.

He also attended events at the White Horse Rider Hall operated by War Chief and Brown Hall near Marty, run by Hollow Horn. White Hall was south of Marty and Fox Kit Society was near the Missouri River.

“There was another one northwest of Marty that they called Round Hall even though it was square,” he said. “That was for some of the Cat Band, and for the mixed-bloods. It was under a man with the name of Good Last Born.”

White Swan Dance Hall was located on the northwest corner of the Yankton Reservation until 1954, but tribal members moved it closer to Lake Andes before the bottom land was flooded by Fort Randall Dam.

|

| The annual Catholic Convocation on the Yankton Indian Reservation during the 1920s attracted Indians from across historic Sioux Country. |

Dances were Friday nights at White Swan. The gathering started when the drum keeper, the dance hall chief, hit the drum. “Then the one that sponsored the dance would call the crier [Ayanpaha] over and explain to him what it was about and explain to him who was the first to be recognized,” Joe said.

The first dedication went to the chief. Then the drummers honored others. “If they had a kettle of dog soup, they’d have a kettle dance and prayers were offered. The man with a stick would be the first one around that kettle. He’d burn some cedar. Four men would go out and dance while they sang that kettle song. They’d ask the man that put up the dog to explain what it was for. Probably it was to go to the singers, or maybe to someone that was to take a traditional medication.” The sacrifice of a dog and presentation of the soup represented an illness or special need.

Then dancing began in earnest. There might be a war dance, a love dance, a round dance, a penny dance or a give-away dance. Every song had meaning. “In the old days,” Joe said, “those dance groups was for the bands [ospayes] but after our people moved to the reservation the bands got all mixed up. Of course, the bands got mixed up in the old days [too]. You have to follow the woman’s side in the Indian way. If you was a Roaster and you married a woman of the Cat Band, you’d lose out on your own band and belong to hers. But even with that crossover, the bands stayed separate under their own leader, and each one had its own dances.” The Rosebud dances were generally open to everyone, while the Yankton events were often restricted to particular ospayes and tiospayes.

When Charlie was a youth on the Rosebud Reservation there was a federal policy to eliminate dancing by anyone but elders. Middle-aged tribal members could not dance, but they could watch. Youth were forbidden to even approach a dance hall.

One night, Charlie and some other youngsters watched the dancing through a window. Suddenly the lights of an automobile approached, so they fled and jumped in a car. Charlie cranked the engine and, with little experience behind a steering wheel, drove the vehicle into the darkness of an open field. The car hit a rock and rolled. He broke his wrist, but no one was badly injured.

Marriages and divorces were part of the dance hall culture. Marriages took place in solemn Sacred Pipe ceremonies or in Native American church prayer meetings. For unhappy couples divorce proceedings were simple. A woman could cast her husband's belongings out of her tee pee or allotment house and declare in a loud voice that she no longer wanted to live with the man. He was then available to any woman who would have him.

|

| The White Swan Dance Hall before it collapsed in the early 1980s. |

A man could attend a pow wow or other gathering, go to the central drum and strike it four times, thus declaring the marriage over. There were no trumped-up charges, no lawyer fees and no court proceedings.

While missionaries and government agents discouraged and regulated dance halls, they promoted assimilation through festivities befitting their own heritage. Joe Rockboy attended Fourth of July games that lasted as long as 10 days. An annual Sioux Fair was held near Greenwood (south of present-day Wagner) in September to give Indian farmers a chance to show products from their allotments.

Shinny was a traditional game played at the fair. “Someone made a ball by rolling up a deer’s tail and covering it over with deer skin,” Joe remembered. “They’d mark off two goals about a quarter of a mile apart. They’d team up on different sides. Each person took a hickory or ash stick about 25 or 30 inches long and they went after that deerskin ball just like in a soccer game. What they was supposed to do was see which team could drive the ball over the opposite team’s goal first. Sometimes they’d play for a half a day. Then they’d rest up and go at it again after dinner. The side that put the ball over the opposing team’s goal two out of three games would win the match.”

Another game called wands and hoops involved throwing spears through a rolling hoop. A hoop man would say something to distract his opponent, such as “I’m a horse thief.” The spear thrower would counter, perhaps, with “I like to scalp horse thieves.”

Yanktons made tops out of buffalo horns by filling them with iron wood (hickory). They put deerskin thongs around them and spun them. The goal was to spin your top longer than the other players. Other games included spear throwing and a dice game using plum seeds with marks on them.

Horse races were also popular. “After the Yanktons got patent-in-fee to their land and started to sell allotments, some of them went out and bought fast horses,” Joe said. He and several of his friends were top competitors in a relay race in which riders brought three horses and changed saddles as they progressed. The total purse was $150 per day, and races were often held for three straight days during county fairs. “Our expenses wasn’t much. We’d travel with dried meat that the white man calls jerky. We done all our own cooking. If you could pick up a purse here and there you’d save a couple of hundred dollars by racing in the summer and that was a lot of help in buying food and clothes for the family in the winter.”

Dance halls, Fourth of July celebrations and county agricultural fairs drew the Yankton and Rosebud people together in a time when their native culture was discouraged, and sometimes forbidden, by their non-Indian neighbors. Even the charitable give-away was banned in some areas because agents and missionaries perceived it as anti-capitalistic, and they were attempting to encourage personal ownership.

Charlie and Joe laughed when they described how forbidden practices — especially traditional marriages and divorces — continued during seven decades of enforced assimilation. Could it be that the non-Indians’ assault on traditional culture only made it more attractive?

In any case, tribal members sought creative and fun ways to preserve their ancestral beliefs and practices, keeping many of them alive and ready for re-emergence in the renaissance of the 1960s.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2012 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments