The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

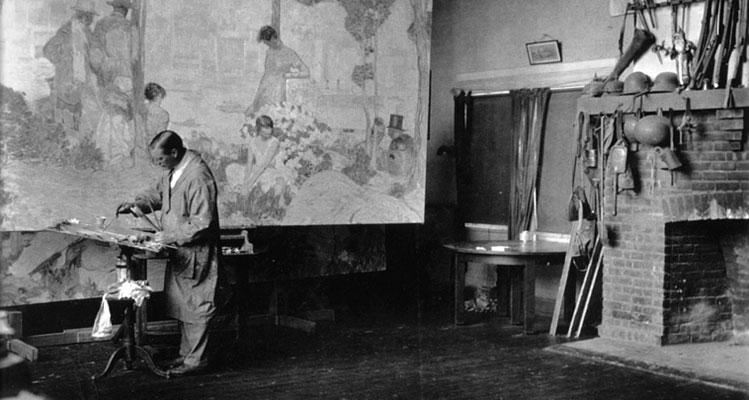

Harvey Dunn, Working Man

|

| Harvey Dunn, working on panels for Lord & Taylor in his studio. |

Fathers and sons don’t always see eye to eye when the younger man comes of age and starts making his own decisions. Thomas and Harvey Dunn certainly didn’t. Thomas thought his boy should stick to farming. Harvey had what his father considered a harebrained idea: he wanted to leave the farm behind and earn his living “making pictures.”

Thomas Dunn lost that particular argument with his strong-willed son; whether he did so gracefully is something only the two of them ever knew.

Harvey Dunn’s first step from the family’s Manchester homestead came in 1901, at age 17, when he enrolled at South Dakota Agricultural College in Brookings. Dunn’s scholastic record in the required courses was nothing if not balanced, with equal numbers of As and Ds, but those studies were of less importance than meeting Professor Ada Caldwell of the art department. She recognized Dunn’s raw talent and encouraged him to continue his education at her alma mater, the Art Institute of Chicago.

|

| The Flame That Cuts Through Sea and Steel. Air Reduction Company, Inc., 1945. |

Brookings hadn’t done much to polish Dunn during his time there. Harvey was still a gangling sodbuster in an ill-fitting suit when he hit Chicago, but he embraced both the clamorous city and, “the splendid freedom given me . . . to pursue the activities nearest my heart,” he said later.

Dunn’s enthusiasm and evident ability couldn’t compensate for his deficiencies in the minds of some. About three months into his time at the Art Institute a delegation of older students took it upon themselves to try and, “discourage him from pursuing a career in art,” wrote Bob Karolevitz in Where Your Heart Is, his biography of Dunn. “Art, they felt, presupposed not only a certain amount of talent, but a high degree of culture and bearing on the part of the artist himself. In their estimation, the raw-boned farmer from South Dakota could never acquire the necessary personal attributes and, therefore, he should go back to his plow before he . . . suffered any bitter disappointments.”

As later become apparent, their ill-advised attempt to “help” did influence Harvey Dunn’s attitude about art and his life’s work — in precisely the opposite direction from the one his would-be benefactors intended.

After two uneven years at the Art Institute, Dunn decided it was time for a change: he packed up his portfolio and headed east for what turned out to be the most significant interview of his life. Howard Pyle, the country’s preeminent illustrator at the time, “liked what the 20 year-old Dunn showed him, and he accepted the young man from Dakota as a pupil,” wrote Karolevitz. “From that moment on [Pyle] shaped . . . the rawboned westerner not only as an artist, but as a teacher and a humanist as well.”

Harvey Dunn’s prairie sensibilities sometimes inclined him to adopt an “off-hand, self-deprecating tone” when talking about his work, according to Karolevitz. That trait was never more evident than in his recollection of the moment he parted ways with the man whose opinion he valued most in the world: “One day, after looking at my work, [Pyle] sighed deeply, and in a voice of a tired and disappointed old man, suggested that I get a studio somewhere else and see if I could get some work to do.”

|

| Illustration for "Bug Eye" by Paul Annixter in Cosmopolitan, August 1944. |

With characteristic verve, Dunn established a studio in Wilmington, Delaware, and started making the rounds of art buyers in New York and Philadelphia. “I cannot claim that it was due to my wisdom that I picked the best time since the Civil War to enter upon the activity I did, for at the time it was just beginning to be realized by advertisers that the weekly and monthly periodicals offered a splendid field, and a great wave of advertising swept the country on a flood of new magazines,” he said. “To supply these, illustrators were in great demand.”

Dunn’s skill and farm-bred work ethic made him an instant favorite with publishers. “Buyers learned they could depend on him, not only for good work but for punctual delivery,” wrote Karolevitz. “He was not a procrastinator nor an esthete who had to wait until inspiration dawned. No wonder he was able, on one occasion, to turn out 55 completed illustrations in 11 weeks.”

Harvey Dunn’s first assignment for a national magazine was a story illustration for the Saturday Evening Post of June 2, 1906. Thus began a long, mostly agreeable professional association. Dunn produced almost 350 illustrations for the Post over the next 40 years.

“Because Dunn was respected by the Post for his ability to get to the heart of a story, he was regularly given manuscripts by the top writers, particularly of frontier life and the Old West,” wrote Walt Reed in Harvey Dunn, Illustrator and Painter of the Old West. Dunn’s Post assignments included artwork for stories by Rudyard Kipling, Jack London and W. Somerset Maugham among others.

Dunn’s professional work was by no means limited to western and adventure subjects. His paintings graced a number of novels, most notably an illustrated edition of A Tale of Two Cities, and more than 30 magazines, from Cosmopolitan to American Legion Monthly. Those who are most familiar with Dunn’s prairie pictures might be surprised to discover he also turned out demure women and manly men for the amorous tales that were a staple of women’s magazines.

|

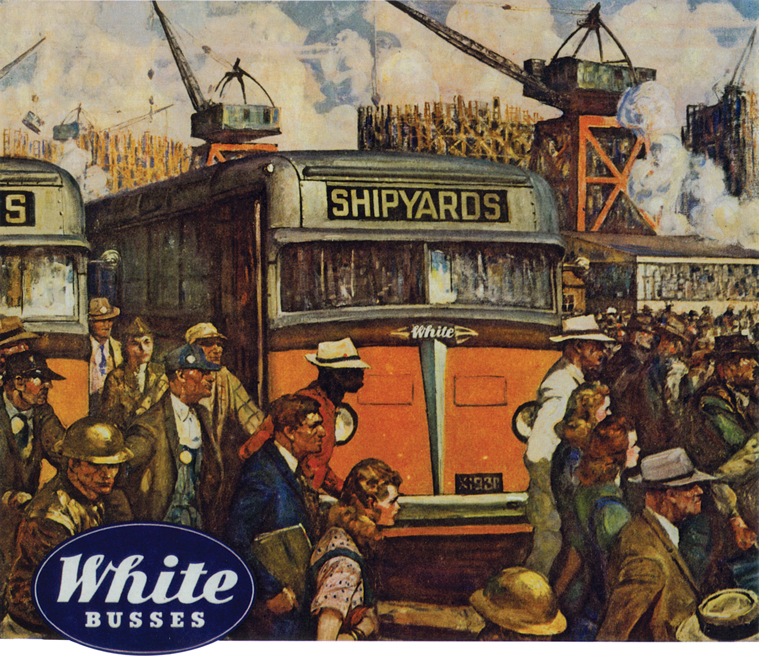

| One of Dunn's World War II clients was the White Motor Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Their campaign featured the uses of buses and trucks in the war effort, illustrated by Dunn's painting titled The work starts at the bus stop - production starts when the worker is delivered, 1944. |

Advertisers eagerly embraced the advances in printing that made full-color illustrations possible in the mass circulation magazines of his era, and that was a boon for artists such as Dunn. His clients included several insurance companies, Steinway Pianos, Maxwell House Coffee and White Motor Company, who commissioned 11 paintings in 1943-44 to publicize how the company’s trucks and busses were contributing to the war effort.

There was the occasional, inevitable clash between the supremely confident artist and buyers who had definite ideas about what they wanted. Dunn would never alter a picture to satisfy a client, according to Dean Cornwell, one of his students, but he would paint another picture for them. In this way he satisfied everyone and kept buyers calling with new assignments.

Unlike “velvet pantaloon artists,” his derisive term for painters who equated starving with purity of heart, Harvey Dunn wholeheartedly embraced commercial work and the profit motive. “Any artist who is a good artist should be able to adapt his skill to the exigencies of the day — to fit his work for the use, commercial or otherwise, for which it is intended,” he said. Dunn consigned “long-haired, flowing tie artists” to oblivion and in their place elevated “businessman-artists” who made $10,000 or more a year as the new standard.

It isn’t hard to imagine Dunn saying as much to his father, who had doubted he would ever be able to earn a living in the field, or to the students who had once disparaged him as uncultured. Time and his determination to succeed on his own terms had vindicated him and proven who the “real” artist was.

Harvey Dunn’s thriving career was put on hold in 1918 when he agreed to accompany the American forces fighting on the battlefields of France during World War I. He was in uniform for just over a year, but it was a fruitful interlude that saw him produce literally reams of powerful, often poignant illustrations of life in the trenches and rear areas.

Seeing the slaughter and suffering and cruelty of war first hand changed the man from Manchester. “After Dunn’s battlefield experiences in France, Cornwell noted, illustrating a mere manuscript was too tame for him,” wrote Karolevitz. Dunn resumed producing quality commercial work at a pace which hardly qualified as malingering, but he also, “began to think more and more in terms of significant and lasting pictures, and when the war dimmed in his memory, his mind returned to the Dakota prairies.”

Where his heart had been all along.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2012 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Melanie Olson