The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Iron Mountain Road

Editor's Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2006 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

The average South Dakotan likes black coffee, thick steaks and straight roads. But we make an exception for Iron Mountain Road, one of the most crooked 17 miles you’ll ever drive.

Iron Mountain Road is part of a highway trilogy—along with Custer State Park’s Wildlife Loop and the Needles Highway. The three together are called the Peter Norbeck Scenic Byway, a route that was proclaimed one of America’s top 10 scenic drive by the Society of American Travel Writers.

All three roads (70 miles total) are must-drives, but Iron Mountain is a lengthy, two-lane demonstration that road construction can truly be an art form. Norbeck, who is almost every historian’s all-time favorite South Dakota politician, helped select the route in 1933, as Mount Rushmore was being carved.

Norbeck, then a 63-year-old U.S. senator, personally explored Iron Mountain, looking for views that best showed off the Black Hills landscapes and the emerging faces at Rushmore. Others wanted the road to skirt the peak, but Norbeck insisted on scenery over economy. Already in poor health when he was scouting the path, he died just three years later.

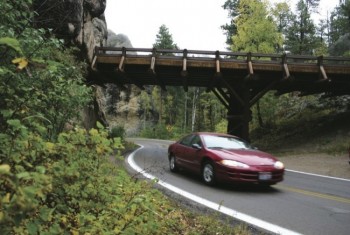

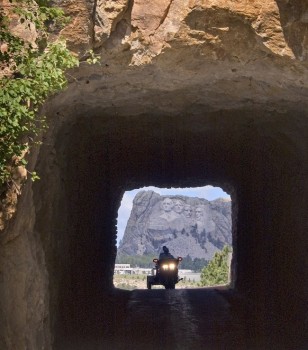

His road squeezes through three stone tunnels, spirals down three pigtail bridges and winds round and round to the 5,445-foot summit where a small parking lot allows visitors to get out from behind the wheel and enjoy a panoramic view of the mountains, including Mount Rushmore.

“I was there as a boy when they were building it,” said Bob Hayes, a retired mining engineer. “They hired miners to do much of the work because it involved drilling and blasting. My father knew the miners, so we would sometimes go watch. I remember being in the tunnels before they were finished. They looked like cave openings.”

Hayes recalled that the workers didn’t seem to appreciate the importance of their task. “Like Mount Rushmore, they weren’t that excited until later. They thought it was just a job. It was later that they realized they’d done something great.”

Although Norbeck gets much deserved credit for the highway because he brought both the political leadership and vision, many others were involved. Gutzon Borglum, chief sculptor of the four presidential faces, saw Iron Mountain Road as “an integral part of the memorial,” according to Gilbert Fite, author of Mount Rushmore.

Also deeply involved was C. C. Gideon, a self-taught builder and designer whose handprints can be found on major projects throughout the southern Black Hills. Gideon built the Game Lodge and designed the artist’s studio at Mount Rushmore after Borglum waste-basketed drawings by the National Park Service architects.

Gideon and Norbeck were a good team; Gideon had the ability to get Norbeck’s dreams not only to paper, but even to completion. The best examples are the pigtail bridges of Iron Mountain Road. The two men decided, after numerous trips on horseback and afoot over the mountain, that the road must be tunneled through the mountain on the way to the peak. Their ideas clashed with all practical principles for road construction in the 1930s.

Finally, the pigtail bridge concept was devised, but state engineers wanted the supports built of concrete and steel. Norbeck envisioned a rustic look that would accent the forest; he turned to Gideon, who designed the bridges of massive wood posts and steel straps.

Gideon’s granddaughter, Marilyn Oakes, operates Buffalo Rock Lodge Bed & Breakfast with her husband, Art, near the south end of the road. “Grandpa was a humble and quiet man,” she said. “I didn’t grow up in South Dakota, but we came back every summer for vacations and got to know him. In my heart of hearts, I see those two guys [her grandpa and the senator] riding on horseback in the Hills, laughing and planning and slapping each other on the back as they agreed on where to take the road.”

Marilyn’s guests at the lodge get an insider’s history of the road that will take them to Rushmore. “The first thing I tell them is that it is narrow and winding to force people to slow down and enjoy the beauty, “ Oakes says. “They could have gone around the mountain very easily but they chose this route.”

Comments

Slats was shaky...poor eye sight and well up in years.. Both he and Mable loved their wine...And Slats loved to drive the Iron Mt. road....usually after a "little" wine....Amazing...he made all those switchbacks on the Silver City Road...then the highway to Hill City and Custer...and the Iron Mt. Road....Slats and Mable are long gone....but I know that I and other long time residents of Silver City certainly remember them....and we were always amazed how Slats could make that trip...summer and winter....uffda!!!!

One of our favorite family stories came from the monument. Dad was overheard by a flatlander explaining the monument construction to his sister. The lady was overheard saying "Ya, and I bet he built this damn road too."