The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

John Banvard’s Brush with Success

|

| John Banvard in an 1849 portrait. |

When John Banvard died in Watertown in 1891, newspapers throughout America and Europe ran his obituary, though it was hardly the kind of attention the town fathers might welcome. Most of the media wondered how it came to pass that one of the 19th century's wealthiest and most renowned artists could die penniless in an American frontier town.

John Banvard achieved international success by fulfilling a boyhood dream of creating the largest painting ever. That might not seem like much of an accomplishment, but when completed, his Mississippi Panorama stood 12 feet high and stretched 3 miles in length. Known to the world as The Three Mile Painting or Banvard's Grand Panorama of the Mississippi, Banvard's canvas depicted nearly 3,000 miles of riverbank, from the mouth of the Yellowstone River on the upper Missouri all the way to New Orleans.

In marking his passing, the Watertown paper printed that Banvard was, "one of the greatest men the world ever saw, and by his genius and skill has made himself so famous that his name will go down in history as such."

That prophecy proved less than accurate; as a matter of fact, Banvard's name is scarcely known today. How his boyhood dream transformed his life from rags to riches is a great American success story. How the man fell back to rags is a story all his own.

John Banvard was the youngest of 11 children, born Nov. 15, 1815, to a prosperous immigrant family in New York City. It was the family's custom to read literature aloud at the dinner table; while still in his highchair, Banvard could recite lengthy poems.

His father died in 1831. On top of that tragedy, his father's business partner absconded with all the family assets. When the destitute family headed to Boston to live with the eldest son, Banvard headed west to seek his fortune.

Only 15 at the time, he found work at a Louisville drug store, but that didn't last long. Banvard was fired after his boss discovered him entertaining his fellow workers by drawing caricatures of their employer on the store walls.

Deciding there was a lesson for him in that experience, Banvard started traveling the Mississippi River system seeking jobs as an itinerant artist. He painted portraits, decorated public buildings, and for a short time worked as a scene painter on the first Mississippi Showboat. The last especially taught him skills that would be indispensable for his later work. He learned a quick brush stroke, how to work from sketches and painting on a grand scale.

Banvard claimed the colossal panorama idea came to him on his first trip down the river. Later, writing about himself in the third person for a promotional pamphlet, Banvard described his experience. "The boy resolved within himself to be an Artist, that he might paint the beauties and sublimities of his native land ... His grand object was to produce the largest painting in the world."

Another story lists patriotism as Banvard's motivation. In 1840 he read a foreign critic who wrote, "America has not the artists commensurate with the grandeur and extent of her scenery." Loyally, Banvard resolved to prove the critic wrong.

The truth probably was that Banvard recognized the panorama's growing popularity, and knew his skills matched such painting. So he bought himself a skiff, some paper and pencils and floated downstream with the strong Mississippi current, sketching all the while.

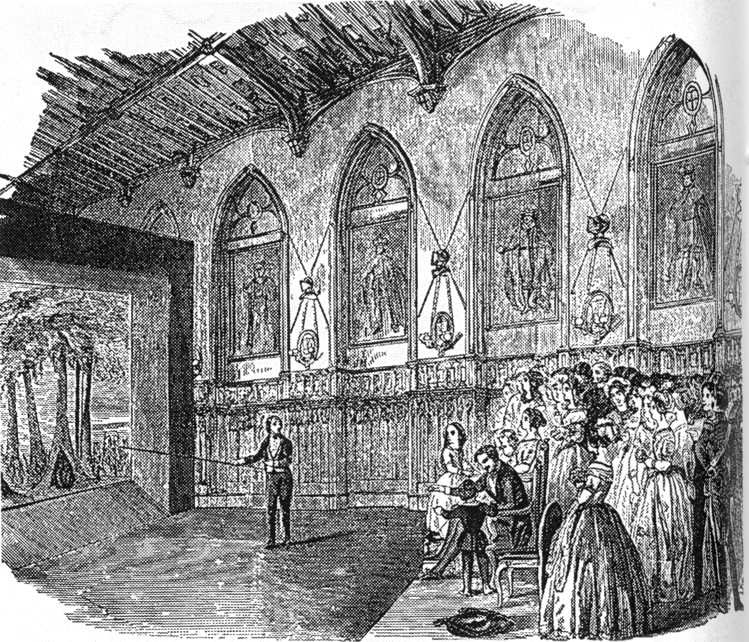

|

| Banvard brought his panorama to England, where he shared it with Queen Victoria and her royal entourage. |

"He would be weeks together without speaking to a human being, having no other company than his rifle, which furnished him with his meat," said one account of his journey. "Several nights he was compelled to creep from under his skiff, where he slept, and sit all night on a log and breast the pelting storm. The sun the while was so intensely hot, that his skin became so burned that it peeled off the backs of his hands and from his face. His eyes became inflamed by such constant and extraordinary effort."

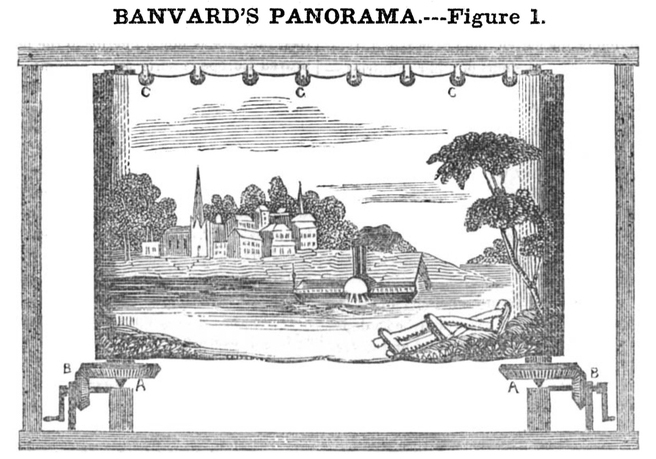

Needing room to accomplish what he had in mind, Banvard started painting in a Louisville warehouse. In order to view his enormous creation, Banvard invented a mechanical device consisting of two tall cylinders attached to either end of the canvas. By hand-cranking these cylinders, the panorama scrolled from one side to the other. To prevent wear, the canvas was not unwound between performances, meaning a customer could sail down river at one performance and head north against the current at the next show.

Banvard's machine used an upper track system that prevented sagging and kept the top tight. This device was such an improvement over existing technology that Scientific American devoted a lengthy article to describing its function.

Upon completing his work, Banvard rented a hall and advertised the unveiling. But nobody showed up. Undaunted, he passed out free tickets along Louisville's docks to the next evening's show. Steamboat crews and dock workers marveled at the panorama's accuracy, and they spread the word in every saloon along the river. The Great Three Mile Painting was showing to full houses by the end of the week.

After a profitable run in Louisville, Banvard headed to Boston. There, after 15 years apart, he was reunited with his family. His homecoming was made all the sweeter when Bostonians flocked to see the show.

Panoramas were the television documentaries, epic cinemas, travelogues and National Geographic specials of their day. That explained the city's enthusiasm for Banvard, according to Dr. John Hanners, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the artist. "The New Englanders' scarcity of knowledge about the West gave such knowledge as there was a peculiar appeal, and Banvard ... was hailed as a contributor to the artistic, educational and scientific knowledge of the age."

So genuine was Banvard's painting that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote descriptively of sailing down the Mississippi in his epic poem "Evangeline" without ever seeing the river. He gleaned all the information needed by attending Banvard's show.

At certain times Banvard admitted school groups in free, which gave the panorama educational and family appeal. Others who never attended mass entertainments started filling Banvard's hall.

In Boston, Banvard perfected his onstage delivery, narrating on stage as the panorama passed behind him. He lectured on science, explained each scene, and told amusing anecdotes. One critic wrote, "Take the artist from the painting, and you take away one of the principle attractions."

|

| An illustration from the Dec. 16, 1848 issue of Scientific American explained Banvard's scrolling machine. |

Unreeling the panorama required two hours. Banvard often expanded shows to three hours or longer depending upon audience reaction. One performance stopped completely when a St. Louis businessman jumped up and shouted, "That's my store! Hallo there, captain! Stop the boat! I want to go ashore and see my wife and family!" The merchant later admitted he believed, at that instant, he was sailing through St. Louis.

As an added attraction, Banvard composed waltzes that a pianist played during shows. His first accompanist was a Boston merchant's daughter named Elizabeth Goodnow. On May 17, 1848, the two were married.

Money poured in. Every night's revenue was placed in a specially designed strong box and protected by security guards. Banks refused to take time counting the money, and accepted the strong box by weight only.

After a performance before the largest audience in Boston theatrical history, Banvard left for New York City. The Three Mile Painting received an equally enthusiastic response there. Unfortunately, Banvard noticed that the constant scrolling had created cracks in the paint. So, he painted another panorama — a near identical copy.

Banvard then sailed for England, where British audiences adored his colorful American stories told in his strange accent. While there Banvard also befriended London's elite, including Charles Dickens. In April 1849, he gave a command performance for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. He considered it the highlight of his career.

Even the normally staid London Times heaped adulation on the visiting American: "Mr. Banvard has done more to elevate the taste for Fine Arts than any single artist since the discovery of painting and much praise is due him."

By this time, Banvard was probably the richest artist who ever lived, and his success spawned hundreds of imitators. Rivals infiltrated art students into shows to have them sketch the panorama. Later, they painted copies from these drawings. Several other London halls advertised the original Mississippi Panorama, but without modern copyright laws, Banvard could do little to defend his work.

Banvard left England in 1850 to travel through Egypt and the Holy Land. From his sketches he completed two more panoramas. One imitated sailing up and down the Nile, while his second depicted the Holy Land on a canvas over 1,000 feet long and 48 feet high. Both were profitable, but neither matched Banvard's original success.

A homesick Elizabeth persuaded Banvard to return to New York in 1852. He built a mansion on Long Island, and called it Glenada, after his daughter Ada.

Banvard started a museum on Broadway that featured his panoramas and legitimate theater, writing many of the plays himself. Unfortunately, this venture proved disastrous.

Unlike the panorama's economic simplicity, the museum required that he deal with hundreds of employees, lawyers and business partners, and Banvard was unequal to the task. Throughout the 1870s, he failed at several other entertainment endeavors. Finally, he lost everything in the Panic of 1877. Creditors seized Glenada and auctioned off his possessions.

His fortune gone, Banvard again headed West. In 1880, he moved in with his eldest son, Eugene, a Watertown lawyer.

Banvard remained active in Watertown by writing. He wrote one of the state's first books, on how to learn shorthand in a week. He became South Dakota's first published poet in 1885 with "Tradition of the Temple," one of over 1,700 poems he composed in his lifetime.

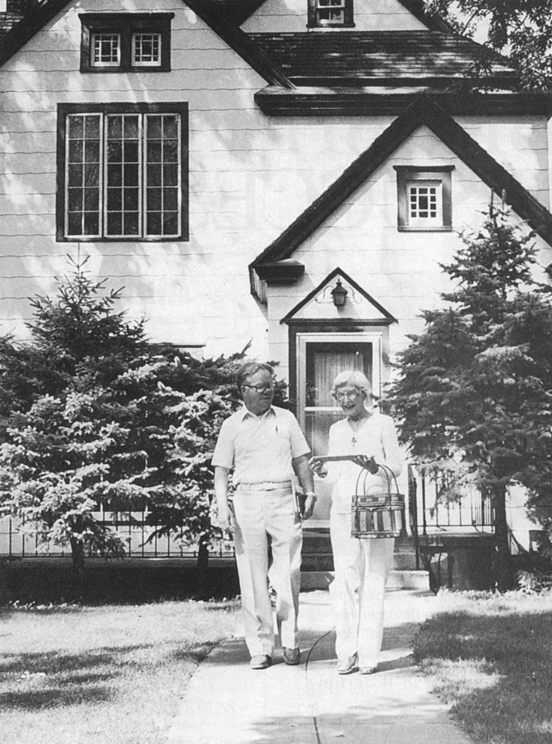

|

| Banvard's great-grandson, John Banvard, visited the family home in Watertown in 1981. |

That same year, Banvard targeted his muse to a political cause. Under his pseudonym, Peter Pallette, Banvard penned a poetic plea to spare the life of Native American activist Christopher Riel.

Some neighbors became offended at their local celebrity choosing unpopular causes. They produced another poem, supposedly written by Riel himself. In it the activist pleads for death to avoid having to read more bad verse. The "Riel Reply" appeared in the Watertown Daily Courier on Aug. 17, 1885:

For Pallette comes with Banvard's muse

to fend me in such verse

That I in haste the gallows choose

the poetry's far worse!

Banvard later learned his neighbors wrote the fake reply, but despite this unpleasant incident, the family thrived in Watertown. Eugene's business prospered, while his father cultivated friendships with town leaders, including Governor Arthur Mellette.

Banvard supervised construction on Watertown's first armory, a building of some local importance. "With the state's National Guard based near Lake Kampeska, (the armory project) proved quite a responsibility," says Joanita Kant Monteith, director of the Kampeska Heritage Museum. The presence of Civil War veterans and an active ladies' auxiliary in the area added even more visibility to the project.

Banvard also gave public lectures on such things as how to read hieroglyphics, which he claimed he had learned to decipher while in Egypt. His lectures always drew good attendance.

His greatest project in Watertown was a grand attempt to regain his fortune with another panorama. The Burning of Columbia depicted the South Carolina capital's destruction by General Sherman's troops in the Civil War.

According to Doane Robinson, longtime secretary of the South Dakota State Historical Society, this last panorama exhibited Banvard's great showmanship. "Painted canvasses, ropes, windlasses, kerosene lamps, shutters, and revolving drums were his accessories," Robinson recalled. "Marching battalions, dashing cavalry, roaring cannon, blazing buildings, the rattle of musketry, and the din of battle were the products, resulting in a final spectacle realistic beyond belief."

Banvard, then 71, ran everything himself. Years later, Robinson put the performance into context. "I have read of the millions expended in the production of a single modern movie," he said, "but when I remember what John Banvard accomplished in a spectacular illusion in Watertown, Dakota Territory, more than fifty years ago for an outlay of ten dollars, I am rather ashamed of Hollywood."

The public loved The Burning of Columbia. The young territory simply lacked the population base to make it the success Banvard wanted. With his family fearing for his health, Banvard finally retired from the stage for good.

In 1889, Elizabeth died; a bereft Banvard followed on May 16, 1891, and was buried at Watertown's Mount Hope Cemetery.

Soon after the funeral, Eugene ran into financial difficulties and the family left town without notice. Creditors once again auctioned off the Banvard family possessions.

No Banvard ancestor lives in the Watertown area today. But in 1981, John Banvard of Bolger, Texas, visited Watertown, searching out information on his once famous great-grandfather. The grandson didn't hold his ancestor's artistic ability in high regard, though. "We have three or four of his paintings," he said, "and frankly, they're so bad we wouldn't put them up on the wall."

Critics have long debated John Banvard's artistic merit. Dr. Hanners disagrees with even judging it as art; he says the shows were more theatrical. Banvard himself said he didn't, "exhibit the painting as a work of art, but as a correct representation of the country it portrays." The public, not Banvard himself, thrust the title "artist" upon him.

Joanita Kant Monteith believes Banvard should be remembered as an excellent example of American ingenuity, "a showman the caliber of P.T. Barnum and Buffalo Bill. They took great American shows to Europe."

In a way, John Banvard's legacy suffered from his own success. By blending moving pictures with words and music, Banvard laid the groundwork for a new art form: the cinema. When the public embraced motion pictures, they forgot what came before.

In 1943, the navy commissioned a Liberty Ship called the USS Banvard. Banvard's daughter, Edith, christened the ship. During the dedication he was proclaimed, "The first motion picture producer." During its three years of service, the USS Banvard encountered several mishaps. Like the Banvard family possessions, the government sold the ship as scrap.

The fate of the Three Mile Painting remains a mystery. One grandchild remembers playing on it as a child. In 1948, Edith Banvard said, "As to what became of the panorama which my father painted, I cannot say with any certainty. I always understood that part of it was used for scenery in the Watertown opera house."

Local legend says Banvard's Grand Panorama was shredded for use as insulation in local houses. If that’s true, then the largest painting in the world, like its creator, still resides in South Dakota.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 1997 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments