The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

John Morrell’s Bloody Friday

|

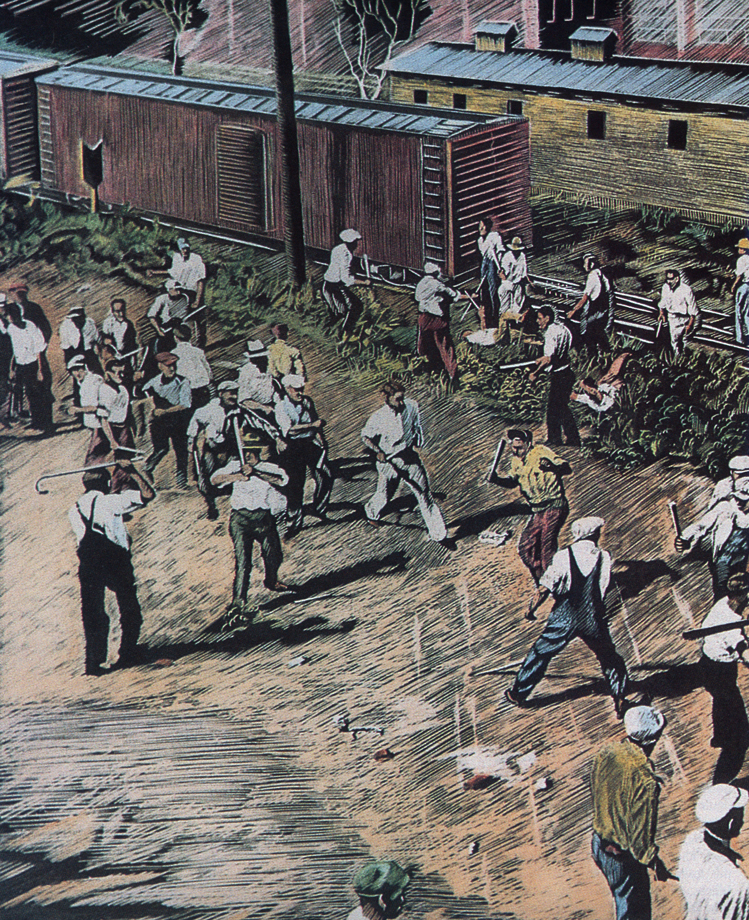

| In this artist's rendition, worker fought worker during the 1935 labor strike at the John Morrell Plant in Sioux Falls. |

On an overcast July morning in 1935, 200 non-union men marched in line, four abreast up Weber Avenue in Sioux Falls. It was the first day of the year's second labor strike at John Morrell & Company Packing Plant. The goal of the march was to break through union picket lines staged at the plant gate. Each man was armed with an oak club. Each was determined to return to work.

At the plant gate pickets were in position, armed less uniformly than the non-union men with canes, baseball bats, broom handles and rocks. The John Morrell plant, a huge dark block of a building, loomed over the picketers. Rail cars, halted by the strikers, sat idle on the tracks west of the street. The strikers stood ready to keep anyone from entering the plant as a part of their protest.

As the phalanx of non-union men marched up the dusty road and over the rise where the railroad tracks ran, Sam Twedell, the union business leader, was asked by a reporter, "What are you going to do, Sam?"

Twedell scratched his head and said, "I dunno." Then he walked forward, alone, to meet the advancing column.

And that began the most violent labor battle in South Dakota history. The conflict wasn't labor versus management. It was workers against each other. The day became known as "Bloody Friday."

In 1935, the John Morrell and Co. Packing Plant was on the edge of a growing Sioux Falls. With few windows in the building, people rarely saw what was going on inside. Between those thick concrete walls, thousands of animals were slaughtered, processed, wrapped and shipped to markets every day.

In the 1930s, Morrell played an even larger part of the Sioux Falls economy than it does today. In a city of about 35,000 the company employed over 1,700 people. It was by far the largest employer and the only major industry in the city. The economic health of Sioux Falls relied on the plant.

The 1930s was the decade of the Great Depression. Nationally, nearly one-third of the work force was unemployed. Crop and livestock prices sat at all-time lows. At the Morrell plant, wages dropped steadily as did the quality of working conditions.

Labor movements were at a standstill. Harsh economic times did not create a fertile landscape for unions to sell their philosophy of worker's rights. The paramount problem of the time was not poor working conditions or shoddy treatment. It was a lack of jobs

In June of 1933, unions got the boost they needed when Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act. Section 7(a) gave labor the right to form unions for the purpose of collective bargaining without interference from their employers. With this opportunity, Morrell plant employees formed Sioux Falls Local 304 of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butchers of North America on Oct. 4, 1933. At a meeting of a dozen or so workers, the first man to join the union was Samuel Twedell. He would become an energetic leader of the union and the organization's business agent.

Twedell was dedicated to the cause of labor. In nearly all of Local 304's disputes at Morrell, he was the main motivator and moral center of the movement. He wanted his union to succeed.

It didn't take long for management to move to crush the infant union. In March of 1935 the company laid off 108 workers, many pro-union.

Local 304 responded to the layoffs by offering to cut the guaranteed workweek from 32 to 28 hours. In addition to that offer, the union complained people were being dismissed without regard to seniority. Some who were let go had been there since the plant opened in 1909.

After management refused to spread the work by lowering the guaranteed hours, Twedell declared the company was trying to break the union, saying the layoff targeted some of the most prominent union members. The 600 members of the union voted to strike.

On a cold Saturday, March 9, at 10 a.m., 700 Morrell workers sat down and refused to work or leave. Workers left the carcasses of 200 swine and 35 cattle on the slaughter lines. They stood passively on the railroad tracks, halting the movement of cars of meat. By noon they had shut down the entire plant.

As the day wore on, wives of the strikers passed cigarettes, dice and playing cards through the fence. Many spent the day chatting at the fence around the plant or dozing on dining room tables, while others listened to a fellow worker play the accordion.

The strike was intended to achieve its goal quickly. Twedell chose the sit-down strike as a way to show a firm front. He thought it would last only 20 to 30 minutes, but it lasted through the rest of the day and into the night.

At 9 p.m., Gov. Tom Berry, a New Deal Democrat and rancher from Belvidere, declared martial law at the request of Minnehaha County Sheriff Melvin L. Sells and mobilized the National Guard to take control of the situation. No violence had erupted at the plant, but state law allowed him to call up troops to prevent property from being destroyed. Plant officials were not worried about the building itself. They were more concerned about meat spoiling as it waited to be loaded and shipped.

Major Eugene L. Foster led 150 guardsmen to surround the plant at 2 a.m. His troops were armed with revolvers, machine guns and tear gas, and ready to eject the strikers by force. It was the first time in state history National Guard troops were called to intervene in a labor dispute.

As guardsmen were about to arrive, Gov. Berry called and asked the strikers to leave the building peacefully. Twedell said the strikers would leave the building once martial law was lifted. At 4 a.m., the Guard withdrew and an hour later they left the building singing and shouting. Picket lines were set up immediately.

On Monday, several hundred employees who wanted to work went to the mayor's office and asked that the streets be cleared so they could get to the plant safely. City Attorney Hugh S. Gamble, acting for Mayor Adolf Graff who was out of town, said he would have the streets open, but he refused the workers' request for a parade through downtown, which he feared would ignite violence.

Later in the week, Gov. Berry called out the National Guard again saying the pickets were disrupting traffic and preventing others from working.

The strike lasted three days. The settlement called for the dismissal of Twedell and 28 other union leaders. As a part of the agreement, employees would hold a vote on seniority rights and would submit the proposal for approval to management. The union agreed to the dismissal of the 29, counting on the National Labor Relations Board to hear the case and demand their reinstatement.

In April, the Labor Board ruled that the men must be allowed to return to the plant. Morrell management rejected the decision, appealing to officials in Washington D.C. However, on May 27 the Supreme Court made the argument moot when they declared the NIRA unconstitutional.

|

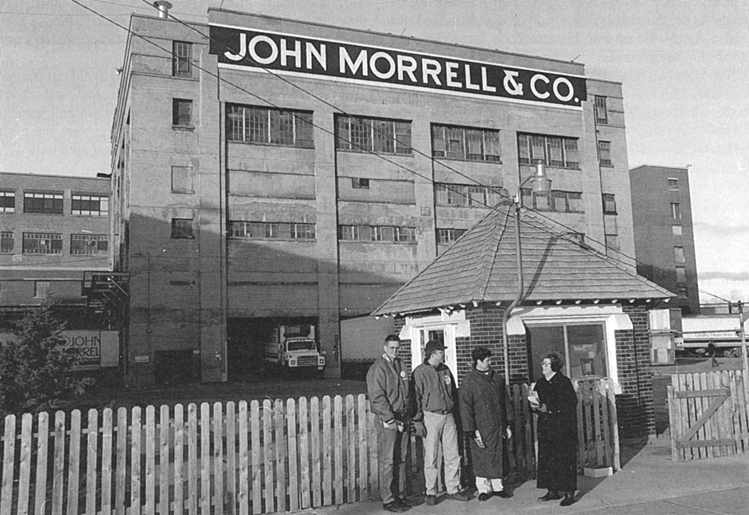

| During its heyday, Local 304 claimed 100 percent membership with about 3,200 plant employees. |

The union ignored the court's decision. On June 8, Local 304 demanded reinstatement of the blacklisted workers, insisted they receive back pay and requested the union's seniority plan be adopted immediately. When their demands were not met, the union again decided to strike. Thursday night, July 18, a picket line was set up. The strike was to last two years.

The first full day of the strike was became known as "Bloody Friday." Early that morning, about 200 non-union employees, mostly foremen at the plant, assembled at the Cataract Hotel. They were members of the Company Association, a group union leaders contended was set up by management so the company could say workers had the right to organize.

This organization had a philosophy much different than the union. In a time of depression when jobs were rare, who was the union to prevent men from working? They were determined to cross the picket line with force and return to work.

Forming a line four abreast, the association marched across the Eighth Street bridge and turned up Weber Avenue toward Morrell. Each man received an oak club from a delivery truck parked near the intersection. The marchers continued up the street to meet the picketers.

As the mass of men advanced toward the picket line, Twedell began to walk toward them, hoping to talk them into respecting the picket lines. The association would have none of it and closed around him as he neared the group. One man with a pipe in his hand yelled, "Let me take him!" He swung the pipe, striking Twedell on the back of the head.

Association men rushed the picket line, and a melee ensued. Blows flew wildly in all directions and screams of rage filled the air. One man was caught squarely on the skull with a club. The noise was described by a spectator as a rung bell.

Non-union men surged through the picket line and about 60 of them made it into the plant grounds. The rest of the men engaged the picketers in over 100 individual fights.

Sitting on rail cars above the brawl, reporters and youth watched the action like it was a football game. "God what a fight!" one young boy screamed. "Kill the scabs!"

At one point in the battle, two union men were actually pounding each other. They each had so much blood running down their faces they couldn't see who they were fighting.

The rest of the association men didn't make it to the plant. Strikers reformed their lines and began pelting their enemies with broken bricks from a nearby pile.

In the middle of the fight stood one lone policeman. M.W. Parsons was a corpulent officer who the year before was held at bay by a gunman while Security National Bank was robbed by thieves identified as John Dillinger's gang. He had as much luck quelling the riot as he did stopping that robbery.

On the fringe of the brawl, City Street Superintendent Walt Keith was watching the action when a man near him was struck with a cane. The frenzied attacker, who was bent on continuing his rampage, raised his cane to hit Keith. As he brought his weapon down, Keith ducked and sent a right hand into his attacker's face. The man dropped to the ground.

"I'm not in on this," Keith said calmly as he helped his assailant, who was spitting out a few recently detached teeth, to his feet. "But if you try to get me in on it, I guess I'll have to protect myself."

Harry Clauson, foreman of the local dock office, and H.S. Thomas, an assistant foreman, attempted to ram their way through the picket line with a car, but the picketers stopped them, smashed the car's window glass, dragged the men out and severely beat them.

J.P. McCoy, a union representative from Chicago, was spotted by some of the foremen who had made it into the plant. They rushed out, knocked him senseless with a club and dragged him into the plant. He was held in the basement under the orders of Herman Veenker, plant superintendent.

"We didn't dare turn him loose because the men were howling for him outside the building," Veenker said. "They would have torn him to pieces."

Veenker later turned McCoy over to the police. The union representative was placed in protective custody.

In all, 54 men, 13 union and 41 non-union, were hospitalized with injuries ranging from minor cuts to fractures and deep lacerations. Men stood in the street with blood dripping down their faces and soaking their shirts. Twedell, who had been on the receiving end of many blows, was seen talking to his wife, his entire head covered in blood.

Later that day, Twedell decided to allow workers into the plant as long as they were actual employees and not strike breakers.

Unlike the March strike, the National Guard was not called out. Although Gov. Berry had threatened to declare martial law again if any violence erupted, on this occasion the Guard would be called out only if local authorities lost control. Sheriff Sells, who had requested state troops for the previous strike, told reporters, "The governor said the task of maintaining law and order was solely in the hands of the local police and sheriff's office."

For the next few weeks, the strike wore on with occasional small skirmishes. Verbal abuse was hurled at workers and women on the picket lines would stab workers with hatpins as they entered plant grounds. Strikers held up a sign with a dead rat hanging from the top labeled, "Here's what you guys are that want to work for Morrell." Another sign had a drawing of a yellow rat.

Not every exchange was filled with animosity. Arthur "Mike" Bailey, one of the men who made it through the picket lines on Bloody Friday, was pictured in the Argus Leader after the fight with trails of blood running down the side of his head. Bailey was allowed to pass through picket lines unscathed. "Hello Mike," one striker said, "I saw your picture in the paper the other day. Go on in Mike, you sure can take it."

Many employees slept at the plant to avoid confrontation with the picketers. The plant held recreational activities for them, including horseshoes and softball games. Kegs of beer were hauled in. Morale in the plant was high but production remained far below normal with only 475 people working.

After the initial days of the strike both sides took on a no-compromise position. About two weeks later, management offered to hire everyone back. A later offer said management would recognize the union and set up an office to hear employee complaints. However, neither offer included rehiring the 29 union officials, so each was rejected.

As time went on the original show of solidarity deteriorated as workers slowly began to return to their jobs. Most had families and children to feed, and the grim reality of the Depression kept them from remaining on strike indefinitely. For those the plant refused to hire back there were relief programs, but most found jobs.

But the union held on, organizing an American Federation of Labor boycott of Morrell products, which was especially effective on the West Coast.

After two years the strike came to an end. But when the settlement came, a plant that was fully manned by non-union workers and in full operation tainted the union’s accomplishment. Morrell conceded to the union's demand to hire back the 29 leaders as positions opened. The settlement was described as a victory for neither side.

In the long run, it was the foundation labor needed. It gave workers a forum to vent their frustrations to management without dreading the consequences. It created the atmosphere needed for open communication so the company and its labor force could work together. Perhaps the greatest lasting effect of the strike was management never questioned the issue of seniority rights again.

For other workers in other industries, the strike set an example to follow. Twedell and his union stalwarts showed what could be accomplished with determination and dedication to a cause. Workers around the state, such as the Teamsters, followed Local 304's lead and worked to organize labor associations.

The violence of Bloody Friday probably wasn't necessary for the eventual victory of the union, but the incident most clearly distilled into a single moment the raw emotion of desperation felt by men and women who were victims of circumstances beyond control.

The struggle of labor in the 1930s was a three-way battle: union against non-union against management. All sides, especially the workers, felt helpless and cornered. In that situation many felt the only option was to lash out.

After the strike was settled, the union made a special effort to smooth things over with their former rivals. A bill was posted around the plant which said, "NOTICE TO ALL MORRELL EMPLOYEES: The strike is over! Let us forget our animosity. Forget the past and organize for the future. We are on friendly terms with the Morrell Company and will do our part to keep this friendship."

Today, Morrell is still an important part of the Sioux Falls economy. In the 1990s, the state showed its commitment to the plant by offering a $10 million incentive plan, which included renovating buildings and updating equipment.

Local 304 now claims over 2,000 members. The union in its heyday claimed 100 percent membership with about 3,200 workers employed at the plant. It doesn't have that same strength anymore.

The last strike at the plant, a sympathy strike for the workers at the Sioux City plant, lasted five months, ending in November of 1987. A Rapid City court declared the strike illegal.

Strikes and picket lines, once considered labor's most effective albeit last-ditch weapon, are hopefully a thing of the past at Morrell. At one time, strikes were defining moments in the relationship of management and labor. Today negotiation is the rule.

Local 304 still remembers that overcast day in 1935. A painting of a birds-eye view of the brawl on "Bloody Friday" hangs in the lobby of the union office in Sioux Falls as a reminder of the conviction of their predecessors and of how things can get out of control.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 1995 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

These union people were the heart and soul of Sioux Falls. Worked hard, showed up every day. Doing hard jobs. Thanks to the union many children in Sioux Falls had health insurance and a good life. College was possible. Union men volunteerd their time free to make Sioux Falls a great place to live. If it were not for unions back then, no one would had made much money. Companies did not pay you out of the goodness of their heart back then. They were greedy. I was proud of my Dad and what he did for our family. Thks