The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

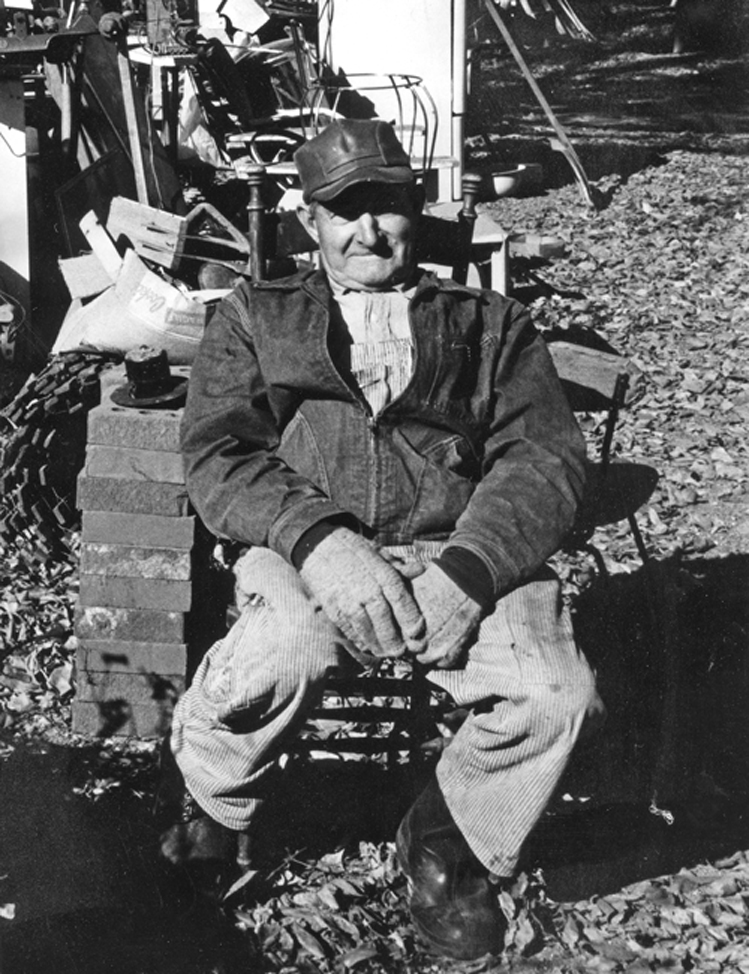

Judging a Junk Man

|

| Emil Tucholke, Milbank's junk man, sold postcards featuring this professional portrait taken by local photographer Milton Fischer to supplement his second-hand business. |

Ted Rathjen was Yankton’s junk man. His white, two-story house near Broadway Avenue in the center of town was surrounded by rusting bicycle frames, old appliances, yesterday’s automobiles, worn furniture, abandoned toys and just about everything else that was once sold as “new” in the downtown stores. Rathjen was a tiny, smiling man who hobbled about on crutches because his legs were crippled from a childhood injury.

In his older years, he just poked his head out from a second story window and advised customers on where they might find what they needed. Schwinn rims were piled beneath the big elm tree. Garden tools were hanging on the picket fence by the road. Toys were in the front of the house by the mailbox.

He suggested a price, and it was usually so low that any negotiation seemed silly. He charged nickels and dimes to kids who needed bike parts, and dollars to adults for the same merchandise. If he was upstairs, he asked visitors to leave the payment in a coffee can on the porch. Ted crossed the highway once or twice a day to have coffee at Sunshine Grocery Store. He fed the store’s penny bucking-horse for kids and always had a smile and a story for the regulars on the stools. Most of the town fathers had bought bike parts or toys from him when they were young, so nobody made a serious attempt to clean up his property until the late 1980s, after his death.

Every town had a junk man. And there were altercations, as with all professions that involve money and territory. One of the most serious situations involved Shorty Miller, a bearded old man who lived in Canton’s town dump by the Big Sioux River until he was 94 years old.

When he died at the South Dakota Human Services Center in Yankton, a local editor memorialized him as “a hermit, river rat, friend of the beaver and blue jay, dump caretaker emeritus, figure familiar, colorful storyteller, character extraordinaire.”

He was also lucky to have reached such a ripe age. In the 1980s some young men tried to infringe on his territory. An argument ensued, and Shorty was shot in the arm and shoulder. He later admitted to also firing a gun. “I got four rifle shots off, just to scare ’em,” he later said. While there were some discrepancies between the two parties’ stories, the sheriff said the dispute “evidently arose over a longtime feud over scavenging rights” at the city dump.

Despite his brush with the law, Miller was known as a friendly hermit who delighted in entertaining visitors with stories about the Big Sioux River. He was a contemporary of another Lincoln County hermit known as Rattlesnake Bill. In his obituary, the editor quoted an acquaintance who said Miller “was a gentle and likeable old guy and when he of- fered you a cut of left-over beaver meat it was hard to say no.”

|

| Ted Rathjen sold old bike parts, appliances and other oddball items at his home along Broadway Avenue in Yankton. |

But none of the aforementioned junk men could hold a discarded candelabra to Grant County’s Emil Tucholke, who took on city hall, won a moral victory, and nearly parlayed that into a political career.

After considering a career in the ministry, Emil bought two small pieces of land west of town along Whetstone Creek. Then he began to collect odds and ends from the citizenry.

Rev. Jack Garvey grew up in Milbank, the son of the postmaster in the 1940s. He remembers Emil as one of his hometown’s most colorful characters. “He was more than just a junk collector,” says Garvey, a Catholic priest. “He had a 1902 Cadillac that he loved to drive in parades. He had a horse-drawn carriage that he would use to travel up and down the alleys, picking up junk before there was any garbage collection. He grew strawberries on a floating raft in the creek. He would bring them into the post office and give them to dad.”

Garvey also remembers that Emil gave his dad a piece of pottery. “It was an old Greek urn of some sort, just a piece of junk I’m sure. But that thing sat on Dad’s desk and I always imagined it was worth millions.”

As Emil’s outdoor inventory grew in size, it spilled over from his land onto a weedy lot owned by the county. Some of the very people who had made contributions to the collection now began to complain, so the county commissioners filed a lawsuit to force him out. Surely they figured that they could evict him without much trouble, but they were wrong. Emil wasn’t about to abandon his domain. After some legal wrangling, a court date was set and the bearded junk man showed up in the courtroom wearing a hangman’s rope around his neck.

Emil acted as his own attorney, and his wit and ready answers seemed to delight Judge Van Buren Perry. The junk man was especially adept at cross-examination. He asked a public official whether he had ever visited the property. The official denied being there until Emil reminded him that he’d visited just the previous Sunday.

“Did you ever buy anything from me?” Emil asked.

“No,” said the official.

“I guess that’s right,” Emil countered. “You just took that stove part without paying me.”

Emil carefully examined all of the state’s exhibits, made numerous motions and objections and invited the judge to recess the proceedings long enough to tour the junkyard. When they returned to court, the judge was carrying a beautiful antique china bowl — a gift for his wife from Emil.

|

| Milbank's famous junk man lived in a covered wagon that he hitched to his horses and rode in local parades. |

Phyllis Justice, the longtime editor and publisher of the Grant County Review, covered the trial. “Over the years, he had built up a huge collection of what some would call junk, but to him it was treasure,” she wrote years later for an anniversary issue of the paper. “Actually, he had preserved some valuable materials, including his prize 1902 Cadillac and covered wagon. In a way he performed a free trash service for residents and restaurants. He fed his team of horses the food thrown out by the restaurants.”

The prosecutor accused Emil of maintaining an “unsightly nuisance area.” Emil countered that the covered wagon, which his horses pulled in local parades, served as his dwelling and an old outhouse was his kitchen and cook shack. He said he was growing strawberries on a raft and feeding beaver.

Justice said that Judge Perry eventually rendered a Solomon-like verdict. In his long opinion, he noted that even though the county commissioners regarded the place as an unsightly garbage dump, there were other ways to describe Emil’s property. “Many years have taught him that some can live on what others waste, and that articles discarded by some have utility and value for others … He has assembled these articles upon his lots … as neatly as his strength and character of material permitted. His stock of merchandise probably amounts to more than a hundred tons, gross, and would probably assay as much as Homestake ore, which runs about $8.00 a ton, I believe.

“Upon these lots we observe an enormous quantity of firewood, the concentration of which no doubt eases the minds of citizens who are apprehensive under the activities of John L. Lewis and the high price of oil. This wood would heat the whole of Milbank for a considerable period,” the judge continued. “There are fruit and pickle jars in sufficient quantities, if used, to tide Milbank over a crop failure or two. Furniture from all periods, some of it repairable, some containing walnut and other woods coveted by tinkers and some only firewood, is piled here and there.

|

| Tucholke scavenged surplus foods like stale bread and rolls and shared them with his horses and chickens. |

“Machinery of all kinds abound. A laundry is dickering for a large churn, which he salvaged from a creamery. Horse-drawn vehicles such as sleighs, carts, surreys and wagons are there, to say nothing of a priceless 1902 Cadillac which runs and which Christopher [locals often referred to Emil as Christopher Columbus] sometimes drives in parades to the astonishment and delight of all.”

Judge Perry was especially respectful of Emil’s independence. “The defendant, disdaining pensions, supports himself and pays taxes on his lots by selling stuff from this stock,” wrote the judge. “Numerous citizens testified that they were able to buy from him much-wanted items otherwise unobtainable. His business is lawful and useful, if a bit unsightly in some respects. It is unique and has some elements of fascination. There is a beaver dam in the creek, with live beavers. To them and to his horses and chickens the defendant feeds stale bread, which he also eats and which the bakeries are glad to get rid of. On a sizeable raft in the beaver pond the defendant raises by hydroponic methods a considerable quantity of strawberries in season.”

In an opinion he clearly enjoyed authoring, the judge also complimented Emil on his “insulated prairie schooner,” his flock of poultry and even his “magnificent beard.” He concluded that the defendant “lives the life of Riley, enjoys himself, supports himself, salvages a good deal of useable material and conserves it so that many people are able to purchase needed items at a saving or which are not elsewhere obtainable.”

But, concluded the judge, “law is law. The lot belongs to the county and the county commissioners have the say-so about it.” In a cunning twist, he granted the county permission to remove Emil’s possessions but he cautioned that any such disposition must be accomplished “tenderly, carefully and with the complete approval of Mr. Tucholke and to see that not the least bit of damage results to [the collection].”

The result was a victory for Emil. “In other words, he allowed Emil to stay on the land since there was no way the county could meet the requirements,” Justice said. “He gave the county its pound of flesh but only if there was no letting of Emil’s blood.”

Emil tried to parlay the ruling into elective office. He ran for state representative in 1952 as an independent. His motto was simple and poetic: “The world is full of corruption and evil — but keep cool and vote for Emil.”

In a full-page advertisement in Justice’s paper, he published Judge Perry’s ruling and then noted, “I handled the case mentioned below without a lawyer. Seems this should be a fair recommendation for any candidate … ”

The eccentric junk man tallied 1,496 votes — a respectable showing but not enough to win a seat among the bland, suit-and-tie crowd in Pierre. Instead, he returned to his business of finding and selling used goods. Now somewhat of a local hero, he became even more popular in local parades. He put a new canvas on his covered wagon for the territorial centennial in 1961. Milbank photographer Milton Fischer took a picture of Emil in an old fur coat and the Grant County Review printed it on glossy postcards that he sold to supplement his second-hand business. He enjoyed hawking them for “a dime apiece or two for a quarter.” When he was no longer permitted to drive, he traded his car for a tractor and used it to collect junk.

In the end, he died alone in April of 1962. His body was found near the railroad tracks that ran by his junkyard. If he hadn’t befriended the local newspaper publisher he might be forgotten. But Justice included a lengthy article on the junk man in the 125th anniversary paper for Milbank.

Like his cohorts in other towns, Emil practiced conservation before most of us understood the concept of recycling. Such men had an aversion to waste and an appreciation for frugality, two traits quite rare today. The junk man saw a need and filled it, and that’s as American as his 1902 Cadillac.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2008 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thank you, Bernie Hunhoff.