The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Sharing Nature's Wealth

Editor’s Note: Sisters Mary and Maud Adams donated the first parcel of their family homestead to the state of South Dakota in 1984. Today, the Adams Homestead and Nature Preserve features walking trails through prairie, forest and riverbank, restored buildings and hundreds of species of flora and fauna. Here’s the story behind its creation from Mary Adams, who died in 2009.

A dream Mary Adams shared with her sister Maud is developing right before her eyes on the family homestead near McCook Lake in the southeastern corner of South Dakota. The sisters, the last descendants of the Adams family, wanted others to benefit from the land as they had. They saw the land as a gift that they should share so others could learn about the area's history and experience the beauty and tranquility of nature.

Driven by a love of the land and an appreciation for education, the two Union County natives donated the farm to the state of South Dakota. But this isn't just any farm. It has been in the Adams family since the sisters' grandparents homesteaded it in 1872. All told it consists of 1,500 acres of prime real estate — an oasis in a bustling commercial development spurred by Dakota Dunes, South Dakota's newest city.

Now, more than 10 years after the sisters donated the first portion of land and more than a year after Maud's death, Mary watches with satisfaction as their donation is being transformed into one of the state's premier recreational areas.

The Adams' gift is incredibly unique, said Marty DeWitt, a parks and recreation official who has been involved with the project from the start. "I'm not that familiar with all the offers that come across the table of the department," he said, "but they are typically donations of land — mainly gifts of farmland or land for game production or wildlife production areas."

Few can compare to the Adams sisters' gift in scale or value, DeWitt said. It is more dramatic considering the recreational use of the property. "It's 1,500 acres of prime real estate in one of the biggest booming areas of the state," he said. "The reason it came about is because they wanted a place for people to learn, enjoy the natural surroundings and experience what the area is all about. Their vision was that it be protected and preserved."

As the Adams Homestead and Nature Preserve, that is happening. Not only will it be preserved, but it will serve as a valuable green space in an area surrounded by the residential and industrial development of Dakota Dunes and North Sioux City and growth near McCook Lake, he said.

Deciding what to do with the land took some thought, Mary said. "My father had the land and he is gone. My mother had the land and she is gone. My brother, Stephen Adams III, was killed in World War II. So it was just my sister and I," she said. "My sister and I were left with the decision. It never entered my mind to sell the land. I thought the land was a gift to me and that I had benefited greatly from the land. I thought it should continue to be shared."

But that thought did enter Maud's mind. "At the time the land value was extremely high," Mary said. Maud considered selling the land and giving the money as chairs to the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. "She was very education oriented, as I was. It became then a question ... what form of education," she said. In the end they decided to give it to the state so people of all ages could learn from it.

The sisters contacted the state. "They didn't have a clue of what we were talking about," Mary said. She said they talked in general about the land back then. Neither she nor the state really knew what the site would become.

"Maud would be shocked. The place has become alive with plans and work and there's a state presence," she said. "I think that this place will be the only intact piece of land of the original settlers in this part of the state. It's shocking but it's true."

A recent visit by two young children and their father convinced her they've made the right choice. A little blond haired boy, about 6 years old, had found a half-awake garter snake. He was so excited and went to the house to ask Mary for a jar to put it in. "He was just thrilled," she said. "When he left, he said, 'You'll save any other snake you find for me, won't you?'"

"Then the little girl found a tree branch that had fallen and was at just the right angle she could jump over it," Mary said. The girl shouted, "Daddy, watch me again" over and over. "I thought, well that's the purpose of the park. They were here a very short time and they had fun and they learned from the earth, the sky and what's between," she said.

During the early years, the project was known as the Adams Nature Area and was considered a low-intensity recreation area, said DeWitt, who was stationed at Newton Hills State Park but now oversees Visitor Services for the Game, Fish and Parks Division. Now, with the homestead, historic buildings, interpretive elements and eventual recreational programs, it's climbed a few steps above a nature area.

Federal funding was secured for trails inside the area but private donations and grants have also boosted the project. That money will enable the state to construct limestone trails and primitive footpaths throughout the property, including a bridge across Mud Lake. A group picnic shelter, a visitor information center and interpretive displays, observation blinds and trailside signs to acquaint visitors with the natural and historical aspects of the area are also planned. The Adams project also will be linked with several trail systems including a bike trail from Sioux City, Iowa.

A 13-acre area will be designated as the homestead site. It will feature historic Adams homes and other buildings. Another 30 acres, not far from the area tabbed for the visitor information center, may be used as an agricultural museum, demonstrating how homesteaders managed to survive and the tools they used. Native grasses also are being planted.

Securing federal funds made a big difference. It allowed officials to take the best parts from the two-phase master plan to create a more complete package of features. That reduced the timeframe of the project from 10 to 20 years to about two years.

Mary's work is also in progress. Her main project involves moving from the historic Shay-Adams house to the original 1880s Adams farmhouse, which she and Maud had moved back to the property. The Shay-Adams house has been there about 70 years. "It's a house of two houses," Mary said. The front part of the house — the front room and two upstairs bedrooms — is the old Shay house.

"It sat about where the Dunes country club is," Mary said. "The old Missouri River was about to cut the old Shay house into the river so my dad put it up on dollies and brought it here," she said. He added the back part later. Mary grew up in the Shay-Adams house and Maud grew up in the old red farmhouse.

All three children attended the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. The two daughters left to pursue careers in nursing and education.

Their parents continued to live on the homestead. Their father died in 1959 and their mother lived there alone during the 1960s. When she became ill, Maud, a nurse who had lived in New York for some time, returned in the late 1960s to care for her until her death in 1977. Later when Maud became ill, Mary, who was serving as acting dean of the College of Nursing at South Dakota State University, returned to the homestead to care for her.

Maud died in 1995. Though she never saw their dream materialize, her presence can be seen and felt everywhere. It was her idea to call it a place for inner renewal, Mary said, and it's very fitting of her and the place.

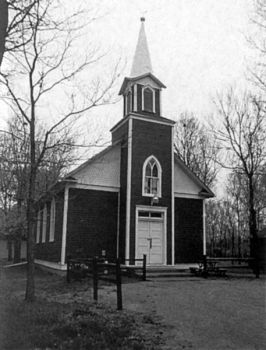

An old barn, a Union County country schoolhouse and an old rural church from the Platte area, which the sisters moved to the place, remain and have been restored. They are situated on the 13 acres and will comprise the homestead feature of the area.

Mary has learned a lot since returning to the homestead. The first was that there were no closets in the downstairs of Shay-Adams house. More importantly, she has learned just how much the place meant to the family and how much of them still remains. "I don't know how my father and mother held onto this place during the Depression," she said. The family lost a lot of land to foreclosure during those years.

"They put three of us through college and two through professional training or professional preparation. I never appreciated what they did until this year," Mary said, acknowledging it required a lot of sacrifice. "But they believed in education and were great believers in the land and how it could be enjoyed.”

One of her mother's favorite books was Sea of Grass. "The idea that you could go out and listen to the wheat and listen to cattails in the wind and hear waves," she said. "Mom's family came from Norway so that part gave her a closeness to family,” Mary said, with tears forming in her eyes.

"When I was acting dean I traveled a lot in South Dakota and I loved to see the wheat fields from Onida down through Winner,” she said. "You really can see and hear the sea of grass."

You don't hear that anymore. The wheat she remembers from her childhood has been replaced with soybeans and hybrid corn. Other things also have changed. "It's totally different than when I grew up. We always called this place 'The Place,’ the 'Adams Place,'" she said. She recalls where the neighbors' places once dotted the landscape and the days when farming was more labor-intensive. Days before 1939. After that year, the land could be worked by machines or horses.

She wishes a small piece of the past can be returned to her family’s land. "I would like to see on this place, these 13 acres, a garden established to represent the Adams women's gardens," she said. It would offer a tribute to her grandmother, mother and sister. "They loved to dig. They loved to transplant. And they loved to water,” Mary said. Though it would take some work to get it established, a century garden representing the plants grown from the 1870s to 1990s would be fitting, she thinks.

As she prepares to settle into the family's 1880s farmhouse, she busies herself inside the Shay-Adams house packing memories and uncovering family papers no one else was intended to find. Though she's finding it to be a difficult, task, Mary remains comfortable with their decision to share the land. She said she has studied the meaning of altruism or selfless regard for the well being of others. It was a gift of love, as she puts it.

But that doesn’t make parting with it any less emotional. "When you give a gift it's not yours anymore," she said, fighting back tears. "I hope the people of South Dakota enjoy it and keep it up. There are a lot of feelings ... here." She takes comfort in believing her deceased family members would also approve. "I think that the positive spirits of my mother, my dad, his parents and my brother and sister are here," Mary said. "I don't think there would be an incompatible voice."

Mary will continue to watch as the dream she shared with Maud develops into a place to be shared. She's also looking forward to the peace and tranquility her family loved about the place. All she needs is a little time off. "I retired," Mary said. "But, honest to God, I haven't had a day yet that I could say, 'I'm retired. What am I going to do today?'"

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 1996 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments