The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Museum Pieces

Nov 7, 2012

|

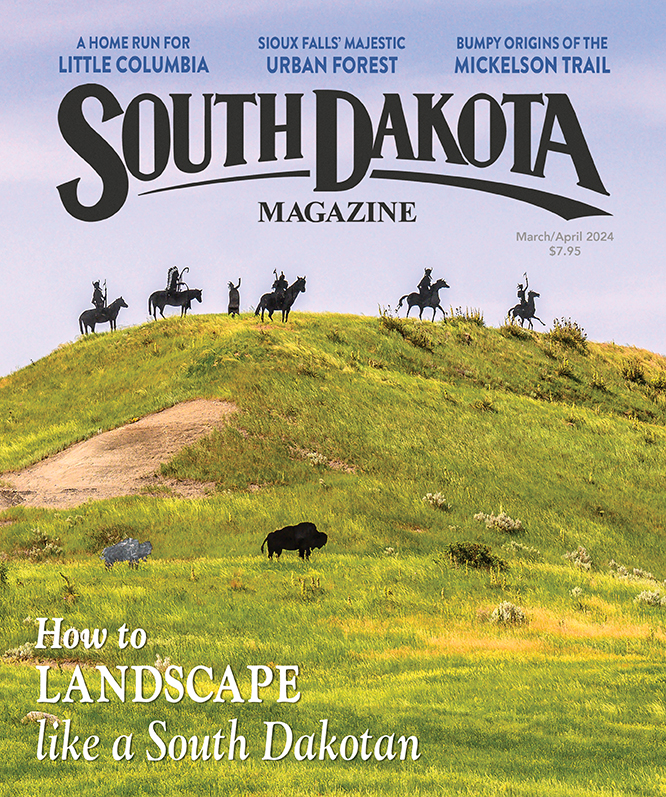

| Lori Holmberg, Dakota Discovery Museum director, says Gilfillan's wagon is a permanent exhibit. |

The coming winter will force South Dakotans to seek indoor amusement, and high on our list should be a visit to local museums. You might be surprised at what you find. Our writers found all sorts of treasures when we did a search for our state’s most interesting and unusual museum artifacts.

Right beneath our noses, in our hometown of Yankton where we publish South Dakota Magazine, we found a Native American pipe bag with an amazing story at the Dakota Territorial Museum. The bag was the centerpiece of a collection of Indian artifacts gathered by Andrew J. Faulk, a 1860s trader and later the third governor of Dakota Territory. Crow Indians probably made the tanned, 43-inch long deer hide bag.

The bag’s recent history is almost as intriguing as its past. In 1995, it was stolen from the museum. For eight years, Yankton County Historical Society board member and artifact collector Larry Ness carried a photograph of the bag, and asked other collectors if they’d seen it. He found it in New York in 2003, and after some legal maneuvering he was able to bring the pipe bag home to the Yankton museum, where it is once again on display.

The Thoen Stone, located at the Adams Museum in Deadwood, is another prized museum piece with an interesting story. The stone is an 8 1/2 by 10 inch scrap of sandstone, purportedly found near Spearfish in 1887 by Louis Thoen. Inscribed on both sides is a message that is still the subject of controversy. The rough script describes how a band of seven men found “all the gold we could carry” in the northern Black Hills, and then were killed by Indian warriors — all except for the writer, Ezra Kind.

Kind supposedly wrote that he was out of food, “without a gun and hiding for his life.” The inscription is dated 1834, 40 years before the Custer expedition into the Hills. The fate of Mr. Kind is unknown, as is the validity of the stone itself.

Another famous stone can be found at the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre — and its validity is certain. In 1742, Pierre Gaultier de la Verendrye sent his sons from Hudson Bay in Canada to find a water route to China. On foot and horseback, Louis-Joseph and Francois trekked west for over a year — until their Indian guides refused to go farther. The French-Canadians did not find a route to the sea, but they were among the first Europeans to see the Dakota plains. Camping with Indians along the Missouri on March 30, 1743, they buried a lead plate on a hilltop near the mouth of the Bad River to commemorate their journey. Three teenagers found the Verendryes’ partially-exposed lead plate in February of 1913. The artifact helped historians map the Verendryes’ route in their search for the Pacific.

Some of other amazing discoveries we found at local museums include paintings, like the Harvey Dunn originals at Brookings’ South Dakota Art Museum, sculptures like Borglum’s Statue of Lincoln at Keystone’s Borglum Historical Center and more Native American treasures like parfleche containers at Akta Lakota Museum in Chamberlain. Sometimes the museum building itself is a treasure, like the Pettigrew House in Sioux Falls or Adams Museum and House in Deadwood.

Ranchers will be nostalgic about Archer Gilfillan’s sheepherder wagon at the Dakota Discovery Museum in Mitchell. The early-day “mobile home,” a double floored and heated covered wagon, came to the museum 50 years ago. Gilfillan, a popular Harding County writer and speaker, was born in White Earth, Minn. in 1886, the son of an Episcopal missionary to the Ojibway Indians. Gilfillan studied Latin and Greek in prestigious universities and traveled in Europe. He returned to the West to homestead in Harding County. That venture failed and he worked for other ranchers, keeping a journal of the people and events he encountered. He gave a speech about sheep, coyote and human behavior at a wool growers’ convention at Helena, Mont., in 1924 called “Secret Sorrows of a Sheepherder,” and it was so well received he compiled his stories into a book, Sheep: Life on the South Dakota Range.

Every South Dakota museum, large and small, has treasures awaiting us. What better time to discover them than on a cold winter’s day?

Comments