The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Poinsett's Enduring Charm

|

| Five generations of Hansons have enjoyed a cabin at Lake Poinsett - including (from right) Jeff Hanson, his daughter Katie, his mother, Elaine, and his granddaughter Hannah. |

For centuries, Lake Poinsett, one of South Dakota’s largest natural lakes, has been a popular stop for visitors attracted by its beauty and its bounty.

Called “the lake of the prickly pears” by early-day visitors wary of the profuse cactus on its shores, it became Poinsett in 1838 to honor then Secretary of War Joel R. Poinsett, also known as the man who brought the Poinsettia plant to the U.S. from Mexico.

Stone and bone artifacts found along Poinsett’s shore and in nearby fields indicate the lake was a popular camping and hunting ground for over 13,000 years. Today it remains a captivating place for residents, visitors, campers, fishermen and hunters. On warm summer weekends, Lake Poinsett’s population may exceed four or five thousand, more than any community within 20 miles.

The deepest of Lake Poinsett’s sprawling 8,000 acres are 16 feet. It holds about 2.5 billion gallons of water, enough to provide wiggle room aplenty for game fish. The lake is one of the state’s largest natural bodies of water, competing for bragging rights with Waubay Lake and Lake Thompson. No one really knows which is largest because sizes vary with the weather.

|

| Harlan Olson (shown with his great-grandfather's skis from Norway) has a collection of artifacts and antiques that were used or found near the lake. |

Most of the lake’s long history can be read from artifacts left by nomads, fur traders and homesteaders. Harlan Olson, a life-long lake resident born on a farm nestled against the lake’s south shore, has been harvesting the lake’s rich history for most of his 70 years.

Olson, a born raconteur and skilled writer, is the lake’s unofficial historian. He’s always had a knack for artifact hunting. Working his father’s fields as a boy, he was constantly spotting something of interest. He has been “hunting” ever since.

His impressive collection is in a museum at Lake Poinsett State Park. Tacked on to the park’s entry-information office, the museum was built in 2007 by the state Game, Fish & Parks Department. The Lake Poinsett Area Development Association donated $15,000, and more in sweat equity, to the museum. Over 2,500 people from 33 states and seven foreign countries visited last summer. As a volunteer museum guide, Olson uses the artifacts he finds as the commas and question marks to punctuate his narration about the lake through the centuries.

He begins with accounts of early nomadic lake visitors. He then segues to the Olson clan of homesteaders. Both nomads and Norwegians of a later time were all drawn to the region for many of the same reasons their fellow travelers migrate there today.

“It’s a Garden of Eden for amateur archeologists like me,” the soft-spoken Olson says. “I can visualize the life that was here thousands of years ago.”

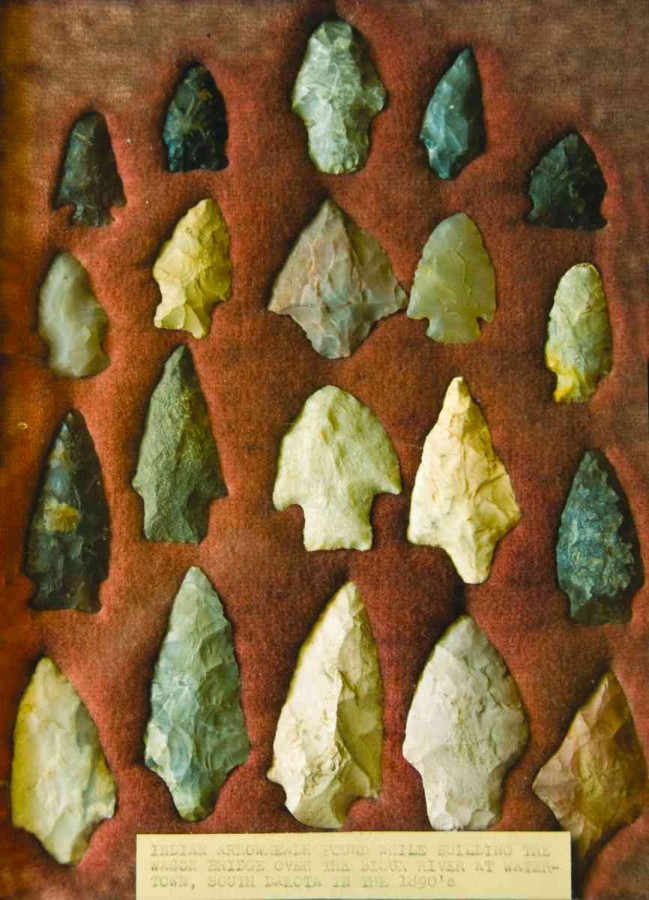

|

| Arrowheads from Olson's collection. |

While the stone and bone objects illustrate time’s distant chapters, more recent Lake Poinsett eras are represented by rusted rifle barrels, a gnarled cavalry spur bent useless by some long ago force, colorful trading beads and other objects lost in the swirling dust of the fur trading days and the hardscrabble times of Dakota Territorial settlement.

Visiting the museum is an interactive, hands-on experience. Visitors can handle stone weapons and tools, heft a mammoth leg bone or gently poke around in a bin of sand in which Olson has buried an array of objects such as authentic Native American arrowheads.

Museum visitors can also participate in Olson’s woolly mammoth spear-throwing challenge. He hauls a mammoth-like target around in his pickup truck (it isn’t nearly as large or as fearsome as the real thing that once tramped and trumpeted through the area). He also crafted an atlatl, a type of sling used by mammoth hunters for greater spear-throwing leverage. Both skill and luck are necessary for a kill, even on Olson’s inert model. He awards few success certificates each season. Olson jokes that the state requires no mammoth license.

Lake Poinsett’s timbered shores have always been inviting habitat for waterfowl and wildlife, although the elk herd reported at the lake in an 1882 story in the Brookings Press may have been the area’s last. The October 1885 issue reported that L. C. Dewing, S. Lyon, C. W. Collier and a Mr. Ripley returned to Brookings from a successful hunt on Lake Poinsett with 205 ducks and prairie chickens.

|

| Revelers enjoy lake camaraderie at the Arlington Beach Resort. |

Poinsett and seven nearby feeder lakes were scooped out by the grinding underside of a ponderous glacier thousands of years ago. Those feeder lakes have remained full the past two years, and Lake Poinsett residents have dealt with flooding.

Connected to Lake Poinsett on the north is another body of water with the oxymoronic title of Dry Lake. It is located at the Stone Bridge on Highway 28, although the historic 1883 stone crossing has been replaced by stressed concrete trusses. Charley and Ida Nitteberg’s renowned Stone Bridge Resort opened nearby in 1906, and the Lakeview Casino dance hall moved to the site later. The dance hall was a cool haven for visitors who danced to the music of Big Tiny Little, Lawrence Welk and other big bands.

The resort, later operated by Nitteberg’s children, had a fleet of 50 wooden rowboats for rent. Its 15 small cabins were booked every summer and even into the fall months, when visiting hunters headquartered at the lake. It’s all gone now, but the stories linger and Stone Bridge remains synonymous with the Nitteberg family.

To the west of Lake Poinsett is Lake Albert, located opposite a wide isthmus. As Poinsett’s few remaining lake frontages are being claimed, Lake Albert’s shoreline is experiencing increased development. This lake was named to honor Colonel John Abert, chief of topographical engineers. Over time, misspellings eventually changed Fremont’s Lake Abert to Lake Albert.

|

| A recreation area on the south shore has more than 100 campsites. |

The recent development of homes on Lake Albert was an impetus for expanding Lake Region Golf Course to 18 holes. Ron Cooley, manager and golf professional for 27 years, has seen club membership grow to over 200.

The Albert-Poinsett isthmus is the most commercialized area on the lake. North-south Highway 81 becomes a four-lane down the isthmus, skirting past three resorts. Another brand new resort is located on the lake’s south side at Arlington Beach.

Miles away on the lake’s east side is the Dakota Ringneck Lodge where farmers Ken and Ellen Hansen cater to hunters. The Hansens also own other nearby hunting lodges and continue to farm along the lake.

Most of the lake’s shoreline is in Hamlin County, but Brookings County claims a sandy-shored sliver on the south side. Except for a few low-lying spots, most of the shoreline is filled with lake cabins and year-round homes. Over 700 residences, many wedged cheek by jowl, line the lake. Some range up to a million dollars or more in price. Hamlin County Assessor Renee Buck estimates total assessed value of lake property in her county at about $64 million. Joyce Dragseth, Brookings County assessor, places lake property in Brookings County at about $11 million.

All that progress brings problems. In the late 1990s a few lake residents tried to form a legal municipality. The idea raised some cane and more eyebrows and soon was soundly defeated in an election.

The most pressing need is more sanitary sewer systems, says long-time lake development supporter Bob Westall. About a third of the lake homes have sewer service, and although the task of organizing other districts and finding funding is daunting, work continues toward a goal of sewage districts all around the lake. Westall serves on the lake development association with Marv Nofziger and Frank Felix, who also edits the association’s newsletter for its 450 members. Felix is a retired banker from Arlington who lives on the lake year-round.

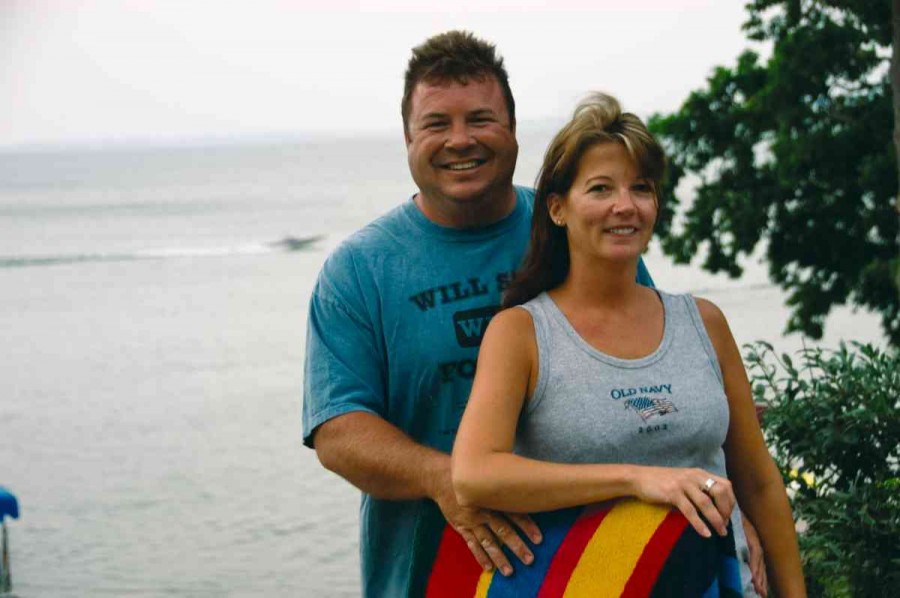

|

| Jody Lemme (with wife Jan) grew up by Poinsett and owned a boat before he had a car. He bought a trailer house on the south shore when he graduated from high school and he has expanded it throughout the years. Their home is now a gathering place for friends from near and far. |

Nofziger and his wife head for Arizona before the snow flies. After retirement as an executive with an office product company, Nofziger and his wife left their home of 33 years in Fresno and moved to South Dakota to be closer to their son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren in Sioux Falls. They selected Lake Poinsett as their summer home because of its proximity to Sioux Falls, but they also liked its beauty, wildlife and golf course.

Nofziger, Westall, Felix and the other board members meet monthly during the summer to work on the problems of lake living. They are developing a website, and they continue to monitor sewage system opportunities, work for better roads and fight the never-ending war against aquatic and noxious weeds. There’s talk of establishing an official weather-reporting site at the golf course, and the board wants the state to install a handicapped fishing and boating dock.

All of the five or six towns within 15 or 20 miles of Lake Poinsett benefit economically from the lake community, but nearby Estelline and Lake Norden are especially blessed.

“It’s huge,” says Tammy Krein of Estelline, speaking of the business lake residents bring to her town. She and husband Ken own the Country Corner at a strategic intersection in the town of 650, where famous author Hayden Carruth edited the local newspaper in the 1880s. The Country Corner is a favorite stop for the lake-bound traveling I-29 from Sioux Falls, Brookings and places in between.

“Our local customers are very loyal, but without the lake customers business would be much different,” Krein says. “They might also stop for groceries at Ward’s Shopping Center, then stop here.”

Across main street from Ward’s is the Red Carpet Lounge, a popular watering hole and eating establishment. Business picks up about 4 p.m. on summer afternoons when lake residents drop in. The Red Carpet and other establishments are also busy when warmly dressed fishermen stop to get supplies and relax after a cold day on the ice.

|

| Don Lappe and his granddaughters planted a vineyard near the lake. |

Business is much the same at the other end of the lake in a little town of 500 called Lake Norden. Situated next to a lake of the same name, Lake Norden is the home of South Dakota’s Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame. There’s also a unique toy museum on Main Street, a gift of the late Don Christman, an area farmer.

While the economic impact of Lake Poinsett is tremendous for Lake Norden, it also got a huge boost of cash and confidence in 2002 when a Davisco Foods International cheese plant came to town.

Jeff and Sharon Jager, owners of Lake Norden’s Jager’s Grocery Store, have reached out to Lake Poinsett residents with a store on the lake’s west shore in the Siouxland Resort building. “So far, so good,” she says.

Lake Norden businessman Rusty Antonen says Lake Norden’s summer youth baseball and softball programs draw youngsters spending summers on the lake with their families. It was Rusty’s father, the late Ray Antonen, who envisioned the South Dakota Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame and raised most of the cash to build it.

Many lake dwellers also attend church in Lake Norden, as they do in Estelline. “Poinsett people are part of our community,” Antonen says, “and people in town can certainly tell by the traffic when the summer season ends.”

Lake Poinsett has enjoyed steady growth since the days when Native Americans following the buffalo carefully walked its shores to avoid prickly pear ambushes. The buffalo and cactus are gone, but Lake Poinsett’s inviting beauty still reaches out to capture today’s nomads who come to enjoy what it has always had to offer.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2009 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments