The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Where Elk Speak

|

| The bugle of an elk is unmistakable and unique. Seasoned buglers can identify individual elk based solely on the animal's call. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

I thought Kevin Lineback was playing me for a greenhorn when he stooped, picked an inch-long elk dropping from the forest floor and pronounced it the product of a bull elk rather than a female.

No, he assured me later, there's a difference in shape — Black Hills outdoorsmen can tell. I should have known Lineback was being straight with me. He has a fine sense of humor, but I've never heard him joke about elk, or about the special place he goes to watch them.

An hour before dawn that cold fall morning, Lineback and I had bought coffee at Spearfish's Mini Mart.

"You didn't use any deodorant or cologne?" he asked, and I answered no. He'd told me the night before that elk can smell those substances at great distance, and that I needed to also avoid bright colors and freshly laundered clothes. So, appropriately muted in hue and naturally scented, we warmed ourselves with coffee as we drove from Spearfish up a gravel road a few miles. Then we hiked along a clear stream in a narrow draw. After 15 minutes, the sky was turning gray as we reached a pool fed by the stream; the mud had been gashed and marked with large hoof prints.

"A wallow," Lineback whispered. Here a bull elk had created its own cologne by digging up the soft mud, urinating in it and then rolling in it. That's part of the rutting ritual each fall, when bulls show off by sight, sound and smell. Then it's pretty much the cow elk's decision with whom to mate and run.

From the wallow we made an aerobic climb out of the draw and walked through wide stands of aspen and ponderosa pine. Not far from where he picked up the dropping, Lineback motioned me behind a wide pine trunk and said, "With luck we'll get you face to face with a bull. Well, maybe not face to face, but real close."

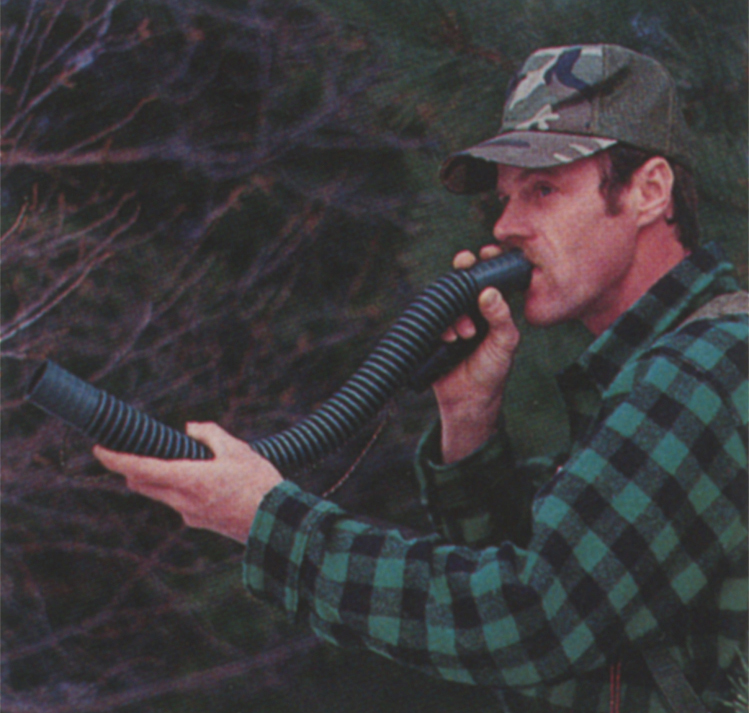

He produced an elk call, an instrument with a latex reed that fits into the mouth, and a 2-foot corrugated plastic tube — a "grunt tube" for imitating various snorts and growls. "Years ago, when I was learning to call, I sounded like a wounded animal from another planet," Lineback once told me. "I drove my wife crazy, and my neighbors. The call fits way back by your wisdom teeth, so when you're learning, you're trying both to get the right sound and to prevent yourself from gagging."

He pierced the still air with a clear, high trumpet tone.

Silence.

Lineback waited a minute, then called again. This time, almost immediately, he was answered. Through the trees floated the sound most symbolic of the natural American West: the musical bugle of the bull elk. And music it is, too rich in tone to be called a moo, or screech or anything else.

|

| Kevin Lineback demonstrates his call, with its grunt tube for imitating snorts and growls. |

Lineback called again. He usually tries to mimic the sound of the elk he's calling, and each animal sounds different. He's been able to recognize certain bulls from year to year by their distinctive bugles.

Again Lineback was answered. How far away was the elk? Quarter mile? Half mile? I couldn't guess. But when it answered a sixth or seventh time, it was suddenly much closer. A couple minutes later we could hear branches and undergrowth snapping, maybe a hundred yards off.

Something huge was moving our way.

Properly speaking, these animals are called wapiti. Once, they ranged as far east as the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. There, English settlers needed to distinguish them from small deer and took to calling them "elk," the term for a European moose. The name stuck. Although they are part of the deer family, they differ from white-tailed and mule deer common to the Black Hills in countless ways, beginning with the way they noisily crash through the forest, and their size. A half-ton bull elk weighs easily four times what a large mule buck would weigh. Also unlike deer, a bull elk mates by attracting a "harem" of 15 or 20 cows, then fighting off other bulls. That's partly what all the bugling is about each fall — the bull Lineback called thought another bull was challenging him for cow rights.

There is evidence that elk roamed South Dakota 35,000 years ago. Plains Indians hunted them for meat and hide, created ornaments from teeth, fashioned tools from bones and antlers and ground antlers to make medicines. Lewis and Clark, in 1804 and 1806, found Manitoban elk on the prairies along the Missouri River, but 75 years later few remained on the Plains. Gold rushers in 1876 found the Black Hills rich with Manitoban elk, but, within a dozen years, they were also gone. Between 1911 and 1920, 200 Rocky Mountain elk (lighter in color than the Manitoban, and with bigger antlers but slightly smaller bodies) were transplanted from the Tetons and Yellowstone to the Black Hills. They thrived and were the beginning of the Hills' present herd, which numbers more than 2,000. Archery and rifle hunting each fall keeps the herd size constant, and the state Department of Game, Fish and Parks, the U.S. Forest Service and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation work together for the herd's well being and for improved habitats.

Bill Aney, wildlife biologist for the Forest Service, has hiked with Lineback to that special place many times. "Kevin's spot is ideal for elk," Aney told me. "It's isolated. There's plenty of water, which isn't all that common in the Black Hills. There's a nice mix of aspen, birch and pine, which makes a cool microhabitat that elk like."

Those are conditions the Forest Service works to enhance elsewhere through road closures for isolation, water catchment and efforts to hang on to aspen and birch growth. In some parts of the Hills, meadows have been cleared for better forage.

|

| During the fall rut, bull elk attract a harem of several cows and then fight for supremacy. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

It hasn't happened in the Black Hills yet, but human population encroachment in parts of the West has led to elk losing fear of people. That brings up another distinction between deer and elk — deer can hurt people when cornered or protecting fawns, but they are Bambis compared to an aggressive, hormone-driven bull elk, in rut with a full set of antlers. Lineback recently read about a bull that terrorized a community in another state until authorities sawed off its antlers.

"They would have been better off killing him," Lineback said. "To send him off to face other bulls without his antlers, and with no way to protect himself from predators, was terrible. They took the crown from the king."

Lineback had told me that a bull's bugle, at close range, is a powerful statement, "a nine hundred or thousand pound animal proclaiming to the world that it's his mountain."

It is powerful, and indeed majestic when you add the visual image of the bull moving in search of the caller, closer and closer, until he stands just 20 yards away.

|

| Elk are much larger than the white-tails and mule deer that also roam the Hills. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

That's how close the bull came to us that morning. Then he stood suddenly still, all 900 pounds of him; Lineback had explained they sometimes pose silently when they know they're near the competing bugler, as if to say, "Look. I'm a force to be reckoned with." I twisted around the tree trunk and snapped a photo, concerned that the bull's white rump would register bright in my picture while the rest of him, grey and brown, would blend into the forest background. And yes, his vast antlers were like a crown, six points on either side. With them he dug at the ground, sniffed the dirt, then sniffed the air. He was deciding something was wrong, that no other elk were present, though he hadn't spotted us. Slowly he lumbered back the way he came, and then ran. Beyond our view we heard him stop, and Lineback, using the same call instrument, began "cow talking" ... a series of mews and chirps. In Lineback's experience, cow talk brings a bull back about nine times out of 10.

But not this one. He bugled back once, and then was finished with us. We realized it was a cold morning for standing motionless, which we'd been doing for several minutes, and we began walking back to the car. En route, Lineback found tracks he knew were made by cow elk ("their hips are wide, so the rear hoof marks are outside the front") and trees where bulls had stripped bark with their antlers. His tracking and calling skills keep Lineback in demand as a guide for elk hunters, but he never brings them to this place.

It's been several years since Lineback's drawn a hard-to-get Black Hills elk hunting tag, but he hunts them annually in Idaho. "Hunting is one way I help take care of an animal I admire," he said as we drove back to Spearfish. "If there were no hunting, there would be immediate overpopulation and starvation.

"An elk means a year's worth of meat for my family," he continued. "Take the animal's weight, subtract about 60 percent for bone and waste, and that's how much meat you've got."

He has no patience for deer hunters who accidentally shoot elk, which happens every year in the Black Hills. "Having hunted both animals, I can tell you there's just no way you should mistake one for the other, because of the size difference. If you can't tell, or just don't care, either way you shouldn't be out there."

The sun had climbed over Lookout Mountain's shoulder as we reached Spearfish. "You know," I said as we drank Mini Mart coffee again, "we've had an experience some people would drive a thousand miles for, and save money all year for.

Lineback nodded. "I can't imagine why everyone who lives in the Hills isn't out there. But I'm glad they're not."

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 1996 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments