The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Making Yellow Magic

|

|

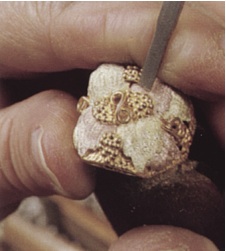

No two pieces of Black Hills Gold jewelry are exactly alike, thanks to the skill of South Dakota craftsmen. |

South Dakota’s iconic jewelry is instantly recognizable because of its three color shades and designs incorporating grape clusters, vines and leaves. Wear Black Hills Gold anywhere in the world, noted Landstrom’s Black Hills Gold Creations President Cheri Lemley, “and it’s an instant conversation piece. As soon as someone recognizes your Black Hills Gold, you’ve got a friend and a conversation about your connection to South Dakota.” The conversation could also center about the myths, legends, legal battles and fierce competition surrounding the coveted jewelry.

The chief legend told by all Black Hills Gold manufacturers in various versions deals with Henri LeBeau. Yes, there really was a Henri LeBeau, probably a French-born goldsmith and prospector who showed up in the Black Hills sometime during the 1870s gold rush. But did he really fall asleep, desperately hungry deep in the Hills, and dream of the vineyards of France? Did he then awaken and decide to honor the vineyards with grape, vine and leaf jewelry? Unlikely.

Still, LeBeau proved a fine goldsmith, opened a shop in Central City and specialized in a vineyard design that was probably seen earlier during the California gold rush. The design moved from there into gold country of Idaho and Montana, and like so many mining camp traditions, made its way east to the Black Hills. Once the design hit the Hills it was irrevocably part of local culture.

|

| Amanda Jenkins models the Black Hills Gold crown worn by Miss Rodeo America since 1965. |

LeBeau passed his knowledge and designs on to S.T. Butler and Butler’s son, George. A couple decades into the 20th century George’s nephew, Frank Thorpe, was producing the jewelry through his F.L Thorpe and Company. Their products fueled the nation’s imagination about the Black Hills as a land with alternative natural laws — creeks that freeze from the bottom up, caves that belch air and gold that’s mined in three colors. In truth the greenish gold found in the jewelry is formed by alloying it with silver. Adding a touch of copper turns the gold pinkish or reddish.

All of this captured the attention of Ivan Landstrom, born in Sweden in 1911, and one of the most dynamic business personalities ever to call South Dakota home. He entered the scene in 1941, setting the stage for a storied business rivalry that spanned half a century. The seeds of the rivalry were planted several years before Landstrom’s arrival, when Frank Thorpe took on Ed Lampinen as a business partner. When the partnership dissolved the two men divided designs and molds dating back to the Butlers — maybe all the way back to LeBeau. Therefore, both could claim their jewelry to be the original item. In 1944, Landstrom, who learned the jewelry business as a diamond buyer for a Minneapolis company, bought out Lampinen, built a new Rapid City production plant and moved aggressively to win retail display space nationwide.

|

| Keystone character "Wild Horse" Harry Hardin, a symbol of Landstrom's for many years, claimed to have ridden with Custer. This would've made him 130 years old. |

Landstrom also obtained a patent on the term Black Hills Gold, which the F.L. Thorpe company had used for at least a quarter century, and then mailed letters warning retailers to beware of other companies using the term in violation of trademark law. Thorpe’s sales dropped sharply, perhaps as much as 65 percent, and the two companies met in federal court. The Thorpe company sued, claiming “maliciousness” in attempting to put Thorpe out of business. A Deadwood jury agreed, forcing cancellation of the patent. Landstrom’s paid F.L.Thorpe and Company $25,000 in damages.

The trial lasted a couple weeks, got lots of newspaper play and, as the old adage goes, there’s really no such thing as bad publicity. Because of the case even South Dakotans not much interested in jewelry recognized Thorpe and Landstrom as kingpins in a major local industry, battling for the attention of retailers in cities coast to coast.

Certainly the lost suit didn’t hurt Ivan Landstrom’s personal reputation. He was touted locally as a pioneer in hiring people with disabilities; he had lost a leg in a childhood accident. It’s bizarre today to read 1940s and 1950s newspaper clippings marveling that a man with a single leg could achieve such success.

In fact, most dark clouds Ivan Landstrom experienced were lined with positive public relations. An estimated $8,000 in gold he lost in late 1946 generated national publicity far exceeding that value. Powdery gold particles were regularly swept from the jewelry production room floor and collected by a filter in the ventilation system. These “sweepings” were taken to a refinery where they yielded substantial dollars in gold. But a maintenance man mistook the sweepings bag for trash and hauled it to Rapid City’s dump.

|

| Dynamic Rapid City businessman Ivan Landstrom. |

A few weeks passed before anyone realized what had happened, and then a great search ensued amid Rapid City’s discarded tin cans, spoiled food and broken household items. Landstrom offered $500 for the bag, then upped the bounty to $1,000. He stressed the bag was “absolutely worthless” to anyone else. “It has to be sent to a refinery,” he told a reporter, “and a federal license is necessary before a refinery would accept the dust.”

Rapid City’s dump was featured in newspapers everywhere. The New York Sunday News reported the lost gold “brought out a gang of ‘prospectors’ to the dump, including bearded old-timers with divining rods, eager students from the nearby South Dakota School of Mines and an Indian medicine man.” But the bag wasn’t recovered. “What a place for the end of the rainbow,” said one searcher, surveying mountains of garbage.

Ivan Landstrom, his wife Mary, daughter Shirley and six other females died in a plane crash on March 17, 1968 on the way back to Rapid City after the girls cheerleaded at the state basketball tournament. His descendants still run the family company. Five generations of the Butler-Thorpe-Waters family ran F.L.Thorpe and Company until it was sold to the West family in 1969. The company continued production in Deadwood for another quarter century, dealt with an intense labor dispute in the 1990s, and was bought out by none other than Landstrom’s in 1995. “So Black Hills Gold history has come full circle,” said Lemley, “with the original designs all back in one company.”

Editor's Note: This article is revised from the November/December 2006 issue of South Dakota Magazine. A story on the cheerleaders who lost their lives in Landstrom's last flight appears in our March/April 2012 issue. To order a copy or to subscribe, call us at 800-456-5117.

Comments

Ed Lampinen, the son of Finnish immigrants, was born in Terraville, SD, in 1890. He was married to Sophie Rantapaa, the sister of my paternal grandmother. Sadly, Ed died at age 55.

Documents supporting this information may be viewed at my web site, goldforothers.com.

I would appreciate any additional information about Ed Lampinen. Please email me at: contact@goldforothers.com if you know of additional information or resources.

thank you-

A. Neil