The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Between the Reservations

Dec 29, 2015

|

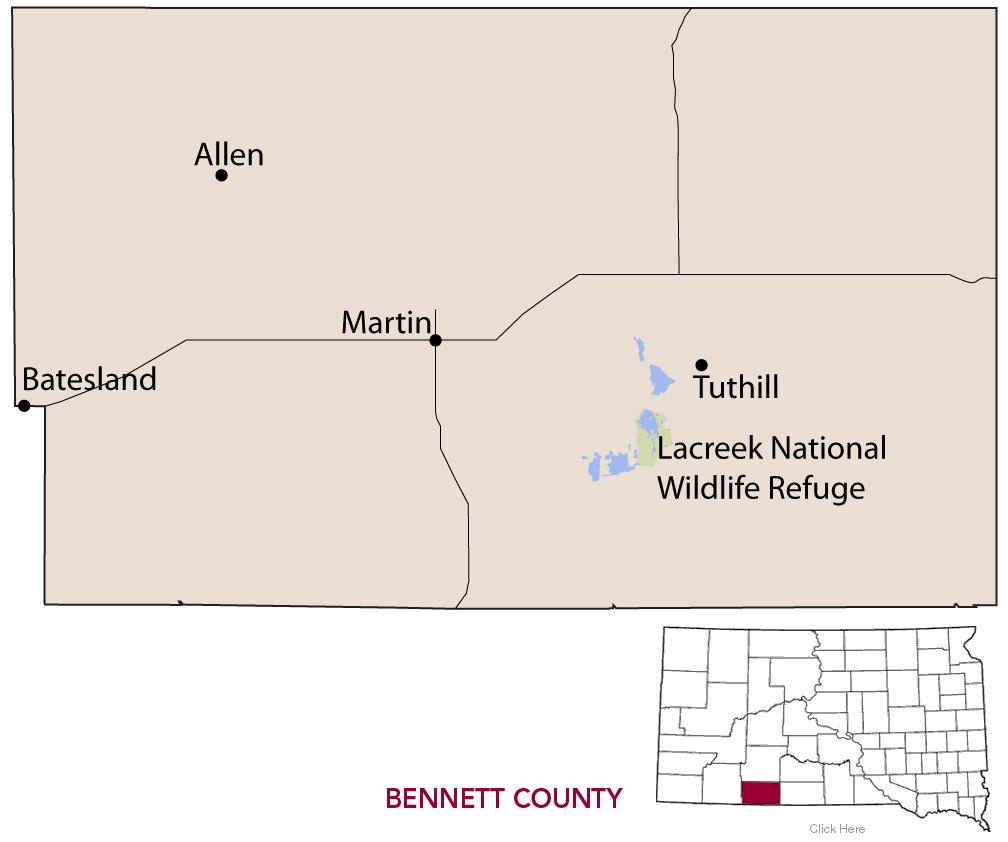

Bennett County, sandwiched between the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Indian Reservations in southwest South Dakota, is the home of one of the country’s most noted Indian scholars. Visitors can still see his old haunts, and while they are there they can observe wildlife found in few other places in South Dakota or see our state’s version of the sandhills that Nebraska has made famous.

Vine Deloria, Jr., was born in Martin in 1933. Before his death in 2005, Time magazine had named him one of America’s greatest religious thinkers. His literary contributions included God is Red and Custer Died For Your Sins, leaving no doubt where the author stood regarding the history of Native and non-Native relations.

Martin greatly impacted Deloria’s thinking, as he wrote years later. “My earliest memories are of trips along dusty roads to Kyle, a small settlement in the heart of the reservation, to attend dances where people danced as if the intervening 50 years had been a lost weekend from which they had fully recovered,” he wrote. “The [Wounded Knee] massacre was vividly etched in the minds of the older reservation people but it was difficult to find anyone who wanted to talk about it.”

|

| Vine Deloria, one of the most celebrated Indian scholars of the 20th century, grew up in Bennett County. |

Deloria’s father was an Episcopalian preacher who served congregations in Allen, Porcupine, Vetal, Batesland, Wanblee and Tuthill. After attending reservation schools and serving in the Marine Corps, the young Deloria studied at Iowa State University. He earned a degree in theology at Lutheran Theological Seminary; but rather than follow in his footsteps as a pastor, he chose a path as an activist educator and writer. He was the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians in the 1960s, and during that period he wrote Custer Died For Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. The book, published during the turbulent years when America was coming to grips with civil rights, challenged readers to reconsider cultural stereotypes, generalizations, patronization and even historical inclinations.

He earned a law degree from the University of Colorado and then taught at the University of Arizona in Tucson from 1978 to 1990, when he returned to Colorado to teach at Boulder until retiring in 2000. Along the way, he wrote and published 20 books and gained a reputation as a gifted orator and scholar.

|

| The historic Inland Theater in Martin was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. |

Fewer and fewer of Martin’s 1,000 residents remember the word warrior, but life continues here just as it did during Deloria’s childhood. Situated on Highway 18, Martin is part of the Oyate Trail, a 395-mile route through southern South Dakota that stretches from North Sioux City to Edgemont. Services are still held every Sunday at the church built by Father Deloria. The rectory where the Delorias lived is standing but vacant.

Zane and Dorene Zieman’s little bookstore on Main Street has a copy of Custer Died For Your Sins on the shelves. Down the street, the town library has four of Deloria’s books. Marsha Fyler, the library director, says they are popular. “Anything with a Native American theme is in demand here, especially his. The Native American population knows about him.”

Bennett County is young compared to its 65 counterparts. It was organized in 1909 and named for Granville Bennett, a justice of the Dakota Territory Supreme Court, delegate to Congress and probate judge in Lawrence County. The land, once belonging to the Oglala Sioux people, was ceded to the federal government and opened to settlement in 1912.

Waterfowl may not jump to mind when discussing Bennett County, but it is home to South Dakota’s only wildlife refuge west of the Missouri River. Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge was created in 1935 as a refuge and breeding ground for migratory birds and other animals. Since its establishment, the refuge has grown to encompass over 16,000 acres in the shallow Lake Creek valley 12 miles southeast of Martin. It helps sustain sandhill cranes, shorebirds and other migratory waterfowl, but its primary mission is to provide wintering habitat for trumpeter swans. The birds were hunted nearly to extinction in the 19th century because their feathers were in demand for quill pens. In 1960, 20 cygnets were released at Lacreek. They were the seed for the High Plains Flock of trumpeter swans that now includes about 600 birds. The best time to view the swans is October through March.

|

| Trumpeter swans, once on the brink of extinction, have been successfully reintroduced at Lacreek National Wildlife Refuge. |

Lacreek lies on the northern edge of the sandhills, a geologic formation that Nebraska has made famous but which begin in southern Bennett County. Just take Highway 73 south of Martin. You’ll pass by farms and fields, perhaps wondering if you’ve yet reached the beginning. You’ll know when you do. The switch from what locals call “the hardland” to the sandhills is literally a line in the sand. They can’t be missed.

|

| Jim Buckles is a third generation rancher in the Bennett County sandhills. |

“There’s nothing like it in the United States, except maybe very locally along barrier islands, a few hundred yards off the East Coast, and in southern California,” says Dr. Perry Rahn. “Certainly nothing to the extent that you find in Bennett County and on into Nebraska.”

Rahn, a retired professor from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City, says the history of the sandhills dates back 2 million years to the Pleistocene, or Ice Age. “The glacier never got to Bennett County and western Nebraska, but the wind from that era might have blown away the topsoil and exposed the sand.”

Though the sandhills have been intensely studied over the past century, scientists remain uncertain of their origins. As the glaciers melted about 11,000 years ago, the dunes took shape. Some call them a “desert in disguise” because the geology is much like dunes found in hotter climates. However, thanks to an average rainfall of 15 inches a year, a thin cover of vegetation makes them look more like Ireland than Africa.

So Bennett County’s sandhills aren’t necessarily a desert, but the county does have the unusual distinction of being the farthest spot from a coastline in North America. Officially called the North American continental pole of inaccessibility, the spot is specifically 7 miles north of the town of Allen.

|

| A group of college students share encouragement and wisdom with an instructor at Wingsprings. |

Bennett County is also helping build bridges between Native and non-Native people. Ten years ago architect and anthropologist Dr. Craig Howe began building Wingsprings on his family’s land north of Martin. It is home to the Center for American Indian Research and Native Studies (CAIRNS). Rapid City native Eric Zimmer, a doctoral candidate in American History at the University of Iowa, says CAIRNS brings together a coalition of scholars, teachers and area residents to bridge the cultural and historical gaps separating Native and non-Native people in South Dakota.

“CAIRNS acknowledges the troubled history and current tensions between many Native and non-Native peoples,” says Zimmer. “It builds bridges through education and stands to improve not only the quality of life but to strengthen the common bonds that hold the diverse residents of this land together.”

If Vine Deloria could see it, he’d surely be proud of his home county.

Editor’s Note: This is the 17th installment in an ongoing series featuring South Dakota’s 66 counties. Click here for previous articles.

Comments

As we've seen with Barack Obama and Donald Trump, promoting tribalism is dangerous and ultimately fatal.

It's time that a new paradigm of community be developed and promoted by and for all, and not the new-age retrospection promoted by this guilted commune disguised as "educational;". Tribalism is a story of failure.

.Bennett County is beautiful. Let's not pretend that this place is part of that beauty.