The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Chasing Cats

|

| Illustration by Mike Reagan. |

In the spring of 1949, Roy Groves was a 64-year-old grandfather who lived with his wife Alice in a little white house just a short walk from Toby’s Lounge, today a legendary chicken shack in Meckling. He stood just under 6 feet tall, was stocky and had the quiet countenance you might expect from the grandfatherly figure shown in black and white photographs with an old fishing hat perched atop his head.

Groves knew a lot about fishing. Some considered him an expert. In fact, during a remarkable four days in May 1949, he pulled two monstrous catfish out of the James River that proved to be state and world records — a 94-pound, 8-ounce blue catfish and a 55-pound channel catfish.

His blue catfish record stood until September of 1959 when Ed Elliott, an electrician from Vermillion, caught a 97-pounder in the Missouri River. It was surpassed again by current record holder Steve Lemmon of Elk Point, who landed a 99-pound, 4-ounce blue in the Big Sioux River on July 21, 2012. But when Groves died at age 82 in 1967, his channel cat was still the state champion, and it remained so until 2019, when the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks issued a ruling that justified what many anglers had long suspected — that Groves’ channel cat wasn’t really a channel after all. His 70-year-old record was voided.

The decision rankled Groves’ grandchildren and great-grandchildren, many of whom still live in South Dakota. But it also rekindled interest in the bewhiskered creatures that swim South Dakota’s waters.

***

South Dakota is home to three types of catfish. Channel cats are the most widespread; they live in rivers and lakes throughout the state. Flathead catfish are found primarily in the Missouri River and its tributaries, the James and Big Sioux, but there is also an isolated population in Lake Mitchell. Blue catfish swim almost exclusively in the Missouri below Gavins Point Dam, though they can be caught along the lower James and Big Sioux rivers, as well.

|

| Flathead catfish are one of three species of catfish found in South Dakota. They swim mostly in the Missouri, James and Big Sioux rivers. Photo by Sam Stukel. |

Channel cats are easily recognizable by their whiskers, or barbels, that extend from the corners of their mouths. Their bodies are drab olive in color with white bellies and no scales. They lurk close to the bottom of a lake or river, preying on crustaceans, insects or other fish. All in all, a slimy-looking catfish may not be the most attractive species to find on the end of your hook, but according to Geno Adams, the fisheries program administrator for Game, Fish and Parks, they are among the state’s most underutilized fish. “We have some absolutely phenomenal channel cat fishing in South Dakota, and they just don’t get used like they do in some other states,” Adams says. “We’ve always been a walleye-centric state. That’s our number one sport fish. Channel catfish are pretty well dispersed around the country. Walleye are not. But these Missouri River reservoirs are absolutely full of fantastic catfish. When people from other states move here and they’re big cat fishermen, or they come for a walleye trip and get winded off the reservoir and the guide takes them into the back of a bay to fish cats, people are astounded by the quality of catfishing in these reservoirs.”

Biologists are currently studying channel cats and flatheads on the James River from Olivet to its confluence with the Missouri. They hope to learn more about their lifespan and how the populations move and grow. B.J. Schall, a fisheries biologist with Game, Fish and Parks who is helping lead the study, says channel cats can be among the most accessible fish for beginning anglers. “Catfishing can be really inexpensive and really easy to do,” Schall says. “You don’t need the equipment that a lot of anglers use for walleye fishing. You can pull up to a bank, throw out a piece of bait that sinks to the bottom and just let it sit. That makes it a little more low tech than the guys who have depth finder systems and sonars in their boats. And if you can get access to a river system, you can just bump onto the bank and fish. It doesn’t necessarily require a boat.”

Anglers like Jason Stansbury fish for the occasional channel cat, but he’s part of a group that’s passionate about landing trophy flatheads. Flathead catfish stay away from swiftly moving water, opting for deeper pools with plenty of cover. They can live a long time, which allows them to grow to monstrous proportions. Part of the Game, Fish and Parks’ research on the James includes taking spines from a catfish’s pectoral fin, which helps determine age. The oldest flathead they’ve discovered to date was 25 years old, and the largest weighed nearly 48 pounds and measured 44 1/2 inches. But they can get bigger. Davin Holland holds the current state record with a 63-pound, 8-ounce flathead caught in the James River.

Stansbury’s biggest is 56 pounds, caught while fishing from the bank of the Big Sioux. “They’re not like catching walleyes,” says Stansbury, the catfishing expert for Wild Dakota, a popular hunting and fishing television program. “These fish are territorial predators. They’re smart fish. I always say that any size flathead you catch is a win.”

Protection for large flatheads is another reason behind the James River study. Avid catfishermen like Stansbury have long been concerned about the potential overharvest of trophy flatheads because in some places there have been no size limits. Schall says biologists have run some modeling based on their current research that indicates any new regulations are unlikely to result in significant changes in the number of large fish in the system. Still, the Game, Fish and Parks Commission is considering a resolution that would limit anglers to one harvested flathead per day that measures more than 28 inches.

|

| Catfish can be caught from shore, but anglers searching for trophy flatheads and blues often spend the night in boats. Photo by Sam Stukel. |

Stansbury caught his 56-pounder in 2019 using a bullhead for bait. The fish bit at around 1 a.m., which is typical given their nocturnal nature. He battled the fish for nearly half an hour before he had it in the net.

Tom Van Kley lives in Sioux Falls and sells insurance for Mutual of Omaha by day, but many nights and weekends find him searching for trophy flatheads and blue cats. He was introduced to catfishing almost by accident. “We were walleye fishing up by Trent,” Van Kley says. “We ended up catching some red horse suckers that we cut for bait, just to see what we could catch. We were sitting by the campfire and our rods just started getting smashed by 8- to 10-pound channel cats. From that night on, catfish just got into my blood.”

Eventually he began looking for even bigger cats, but the transition wasn’t easy. “The first year that I primarily targeted flatheads I didn’t catch one all year long,” he says. “Then finally, on our last trip of the year down in Omaha, I caught two out of the Missouri River. The next year I didn’t catch one until July. But then I went out with a guy who really knew what he was doing and he kind of showed me the ropes. We just smacked them. We caught eight or nine fish that night up to 25 or 30 pounds each, and I never looked back.”

His biggest catch came during a tournament in Sioux City. He was fishing near Dakota Dunes on the lowest stretch of South Dakota’s Missouri River. “We were sitting on this spot that I thought would be pretty good, but it was midnight and we had no fish. And the weigh-in was at 2 a.m. My buddy wanted to call it a night, but I said, ‘A lot can change in two hours.’ About 35 minutes later one rod folded and we had a 20-pound fish on.”

They rebaited their hooks and waited. Then, out of the corner of his eye, he saw another rod bend. He grabbed it and less than 10 minutes later reeled in a 56-pound flathead. They won the tournament with 76 pounds of catfish. “We’re usually fishing from 7 p.m. until the sun comes up,” Van Kley says. “You put in a lot of work to catch a few fish. If you pull in three or four flatheads in a night, you did pretty good. You put a 50-pound fish on the floor and it’s pretty surreal.”

It’s a thrill that Roy Groves knew well.

***

Groves awoke at 5:30 on the morning of Sunday, May 22, 1949. An hour later he was unfolding his chair at one of his favorite fishing spots, about a mile north of where the James River flows into the Missouri just east of Yankton. He cast out two lines — one a 20-pound test line and the other a little heavier — using crawfish and chub minnows for bait. “He cast from the bank into a spot that he was pretty familiar with,” says Marc Rasmussen, a senior vice president at BankWest in Pierre and Groves’ great-grandson. “He knew there had been some fish out there, but he wasn’t having a very good day. He sat there for a long time and only picked up one carp. He kept having his minnows chewed off the line, so he knew something was going on down there, but he couldn’t quite figure out what it was.”

Groves fished for nearly 12 hours that day. Shortly after 6 p.m., he put his last chub minnow on the 20-pound line and cast it out. Two minutes later, “Wham! It felt like I hooked a submarine,” he later told a local newspaper reporter.

The fish swam about 15 feet before Groves set the hook, but that didn’t faze it. The giant cat took about 100 yards of line off Groves’ reel. “She did what she wanted with the line after that,” Groves recalled. “After a half hour to 45-minute fight, she just dove to bottom and stayed there.”

|

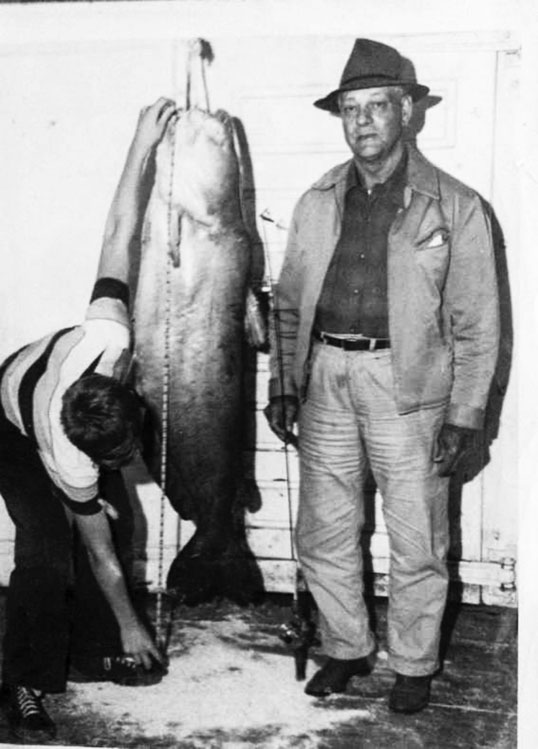

| Roy Groves of Meckling is pictured with his 94-pound, 8-ounce blue catfish (measured by grandson Gary Groves), which set a state record in 1949. It was the second record catfish Groves had caught that week. |

Groves grabbed a pair of pliers from his tackle box and started hitting his fishing pole. The vibrations traveled along the taut fishing line, rousing the cat into another burst of swimming. Groves’ hands were already bloody from trying to stop his reel. His line was quickly running out. Finally, the fish stopped fighting, and at 8:20 p.m., Groves pulled his state record 94-pound, 8-ounce blue catfish ashore.

Rasmussen remembers seeing the big blue mounted above the fireplace in Groves’ home, right next to the Shakespeare rod and reel he’d used to land it. In fact, when Shakespeare heard about Groves’ record-setting catch, they supplied him with new equipment for several years. “The fish was a big part of his life,” Rasmussen says. “He wasn’t a boastful guy, but whenever he would talk to the kids and grandkids, he’d talk a lot about how proud he was. People used to follow him around. He’d have to sneak out to go fishing because they would all try to get into his spots.”

Catching one monster catfish would have been enough to secure his angling legacy, but the blue was actually the second record cat he’d caught that week. Four days earlier, and about 200 yards farther downstream on the James, he landed the channel catfish that eventually became the subject of intense scrutiny within the South Dakota fishing world.

For 70 years, fishermen, biologists, ichthyologists and anyone else intensely interested in catfishing looked at the old black and white photos of Groves standing alongside his champion channel, examined the fin structure and wondered if it wasn’t really a blue catfish. “It was always presumed to be a channel cat,” Rasmussen says, “and there are channel catfish that have been caught since that time in other states that have been bigger.” (The current world record is a 58-pound channel taken from a reservoir in South Carolina in 1964, though there are questions about that fish, too, since the largest channel catfish generally weigh in at 30 pounds or a little more.)

“I think for many people in South Dakota, the real question was, ‘How does a channel cat get to be more than 35 pounds?’” Rasmussen says. “The nature of them is to be a smaller fish. But when you look at the type of fins, the tail fins on a channel cat are a little bit sharper and the fin near the tail is squared off. They say very clearly that it’s not the color of the catfish that makes that determination, but I think at that time they didn’t know better.”

Geno Adams began hearing the questions when he took an administrative position with Game, Fish and Parks in 2009. “Ever since then I’ve gotten emails or calls asking why we wouldn’t turn over that state record because everyone knew that it was not identified correctly,” Adams says.

He shared the photos with fisheries experts at South Dakota State University and other ichthyologists around the country. Their opinions were overwhelming. “It was resounding,” he says. “It didn’t take people long to look at it. They could tell by the anal fin that it was not a channel catfish. When 100 percent of the people are instantly saying it’s not a channel cat, it’s time to do something. I wanted to do this for channel catfishing and channel cat fishermen. It’s a pretty cool thing to have a state record, and to have this category be inactive forever because of a misidentification didn’t seem just.”

Game, Fish and Parks announced in May of 2019 that the channel catfish record would be voided, almost 70 years to the day since Groves pulled his trophy out of the James River. Rasmussen and other family members were initially upset, but given nearly a year to examine the evidence themselves, they’ve come to agree with the decision. “This is not taking away from Roy’s prowess as a cat fisherman,” Adams says. “He was a legitimate catfishing expert, probably one of the best cat fishermen of all time in South Dakota. He was like the godfather of catfishing in South Dakota, and we did not want to take anything away from him or the family.”

The announcement coincided with the launch of Catrush 2019, a campaign designed to generate interest in catfishing. With a new state record up for grabs, anglers responded. On May 20, just three days after the record was voided, the new benchmark was set when Chuck Ewald caught an 8-pound, 3-ounce channel cat at Whitlock Bay. His record lasted only two days. It fell another six times by June 10. Drew Matthews holds the current state record with a 30-pound, 1-ounce channel caught in a farm pond by Murdo.

Though voiding Groves’ long-held record was a difficult decision, perhaps he would have been happy to see fishermen taking the same joy that he did in chasing the elusive cats. “We knew it wouldn’t be the easiest thing or the most well received by those who are involved in that record, but we also knew that the vast majority of people out there were going to be happy with the decision, and that’s the way it’s turned out,” Adams says. “I heard countless stories of people going catfishing who hadn’t gone in 20 years, or they’d never gone before, and they decided they wanted to go try to catch a state record channel cat. From that aspect it was a success in highlighting channel cat fishing in South Dakota.”

Even Rasmussen has gotten in on the fun. He and his wife live along Lake Oahe, where they enjoy fishing for walleye, northerns and catfish, but nothing like the behemoths that his great-grandfather caught. His biggest is a 12-pound channel. “That’s enough of a thrill for an old man like me,” he says.

Still, monstrous fish lurk in the murky waters of South Dakota’s rivers, waiting for someone with the right combination of skill, time, patience and stamina to land them.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2020 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments