The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

A Presidential Summer

THEY CALLED HIM "The Man Who Hates Everything," and no one ever did more to deserve their reputation. H.L. Mencken, writer, social critic and professional deflator popular during the 1920s, made a living lambasting ministers, doctors, Southerners, teachers, his fellow newspaperman and just about everyone else in the country. So when he took aim at President Calvin Coolidge no one was likely very surprised at what came from his toxic typewriter. "Coolidge's chief feat," wrote Mencken, "was to sleep more than any other president." Not only was he lazy, but the President's perpetually dour expression seemed to indicate he had been "weaned on a pickle."

People expected that from Mencken. But it was difficult to find anybody who had really good things to say about President Coolidge. "In appearance he was stupendously null," remembered one of his neighbors, "as if he was lacking in red corpuscles." Shy, lacking in social graces, almost totally devoid of wit — Coolidge was all of those, and less. To the people at large he was Silent Cal, a stern, no nonsense Vermont Yankee who spoke as if he expected to live 100 years, but feared he had mistakenly been given only enough words to last half that long. Among the nation's opinion makers he was considered an incredible dullard, if not a fool. He was popular with the business community, but that was chiefly for his stolid determination not to do anything that might rock the economy; he was a chief executive, said one congressman "who raised inertia almost to the level of a way of life." But it fell to Dorothy Parker's acid tongue to deliver the unkindest cut of all. In 1933, when she was informed that the ex-president was dead, her response was, "How do they know?"

Obvious though his shortcomings might be, he was still the President of the United States. Which meant newspapers took note of whatever he was doing and wherever he was doing it. And that gave some people from South Dakota an idea. Looking for a way to publicize the Black Hills nationally, Sen. Peter Norbeck and a number of others hit upon the idea of inviting President Coolidge for a visit. And by a fortuitous combination of circumstances, Silent Cal accepted.

In the days before air conditioning, summer reminded residents of Washington, D.C., that their city had been built on a swamp. It was usually hot, muggy and uncomfortable. Everyone who could left town for as much of the season as possible. Coolidge, whose bronchitis was aggravated by these conditions, suffered more than most. In 1925 he had escaped to the Massachusetts shore; the following year found him in New York's Adirondack Mountains; for the summer of 1927 he resolved to vacation somewhere "west of the Allegheny's and east of the Rockies."

That was South Dakota's signal to launch an all-out offensive aimed at convincing Coolidge to choose the Black Hills. The state Legislature passed a resolution formally inviting the president on Jan. 7, 1927, and in the words of Rex Alan Smith, ‘‘they spared no adjectives when drafting it, and indulged in no false modesty." There was mention of lofty peaks, magnificent forests, sparkling streams and an "ideal" climate, of course, but also, "splendid fishing, golf, polo and tennis." To tie it all up neatly the Legislature sought to assure Coolidge that the stories of gunslingers and ladies of the evening were all in the Black Hills' past. "The population in and about the mountains," they declared, "is intelligent and moral."

When Sen. Norbeck delivered the invitation, Coolidge was suitably impressed, resulting in one of the few instances of wit recorded during his administration. "Senator," he observed dryly, "I can't tell whether this is a chapter from Revelations or Mohammed's idea of the seventh heaven." True to his nature, though, the president said nothing further that day.

His frustrating silence continued for two months. In the spring, one of South Dakota's two congressmen, William Williamson, met with the president to present the state's case yet again.

"How are the flies and mosquitoes out there?" Coolidge asked.

"In the mountains proper, few or none," replied Williamson.

"That's good," said Coolidge. "Last place I went they nearly pestered me to death."

It seems the Legislature should have dispensed with all that chatter about scenery in their invitation and concentrated on the insects. Another advantage that they neglected to mention was the relative lack of people in the Hills. Coolidge had been annoyed on other trips by crowds who gathered to gawk at him. He was pleased that Rapid City, population 8,000 and the only town of any size in the area, was a considerable train and automobile ride from where he was going to be staying.

Before the final decision was made, Coolidge dispatched Colonel Edward Starling, head of the White House Secret Service detail, to inspect the facilities. Starling left the state after two days without a clue as to what he thought of the place, and once again the White House was silent.

For the next month there were almost daily news stories speculating on whether or not the president was actually coming. There wasn't a word from Washington until May 27, when Colonel Starling and several assistants arrived unannounced at the Rapid City train station. Later that day every major newspaper in the state received a telegram from Sen. Norbeck's office; in their next editions, using type generally reserved for a declaration of war or the seventh game of the World Series, the headlines blared, "President Coolidge To Arrive June 16!"

Preparations for the president's visit had started long before anyone knew if he was even coming for sure. Now that it was confirmed, things went into high gear. Coolidge's home while in South Dakota was to be the State Game Lodge in Custer State Park. The president and his wife would stay in the Governor's Suite, which was a bedroom and private sitting room, with a bathroom down the hall. A new coat of paint was applied inside and out, and a sawmill on the grounds was moved two miles over the hill so as not to spoil the presidential view. Extra lines were strung to handle the increased telephone traffic, the lodge was primped and swept one last time, and everyone hoped that nothing had been forgotten. Colonel Starling pronounced himself satisfied.

Coolidge traveled with his wife Grace, staff members, Secret Service agents, three dozen or so newspaper reporters, the first family's two collies, Rob Roy and Prudence Prim, and Mrs. Coolidge's pet raccoon, Rebecca, who lived in a wicker basket. As the train passed into the state at Elkton, the party was joined by Sen. Norbeck and as many other local notables as could wrangle an invitation. An elderly gentleman, not part of the official delegation, climbed aboard in Lake Preston to pay his respects and the train pulled out of the station before anyone noticed.

After yet another formal reception in Pierre with Gov. Bulow and friends, the Coolidges arrived at Rapid City late in the afternoon. The local National Guard band played "Hail to the Chief," probably the first and only time it ever rendered that particular tune, while artillery on the Box Elder firing range thundered a 21-gun salute. There was a dance at the Alfalfa Palace that evening, but Cal and Grace had a quiet supper of elk steak at the lodge and then retired.

Early the next morning Coolidge prepared to set out for his summer office in Rapid City. Some South Dakotans who hoped to establish the Black Hills as a fishing haven intercepted him, and they had made their plans well. Though the president was reluctant at first they convinced him to try his luck in Squaw Creek. Wearing a suit and straw boater, no angler in history ever looked the part less, or had a better chance to catch fish. His hosts did everything but throw the trout in his basket for him.

About a mile above and below the lodge park officials had installed fishnets across the creek. Into this pen they had dumped more than 2,000 trout from the state fish hatchery in Spearfish. These were not small fry, either. They were "tired old breeding trout ... (that) the hatchery had been planning to gel rid of anyway," wrote Rex Alan Smith. "Years of lazy living on ground liver and horsemeat had left them fat and flabby. But they were big, fearless and eminently catchable."

Gov. Bulow, who was in on the plan from the very beginning, would pay for his sins. He and his wife were invited to the lodge for supper one evening and the main course was trout, which, the president proudly explained, he had caught in the creek. "(From) the first bite I took," Bulow recalled, "I could taste the liver and horsemeat on which that trout had lived for years ...." President Coolidge did not seem to mind, though, and the fishing was a good part of why his planned three-week vacation in South Dakota ended up lasting three months.

There was one other person in the Hills that summer who was scheming to use the president's presence for his own purposes, and that was Gutzon Borglum. Rushmore's sculptor was well aware of how the publicity surrounding a presidential visit could help his project; it might even push Coolidge to endorse the idea of appropriating federal funds for the carving, which Borglum hoped would free him from his perpetual need to raise money.

Borglum decided to hold a dedication ceremony on Aug. 10. He had already dedicated the mountain in 1925, but Borglum never let logic get in the way of a good time. It was typical of him that he scheduled the event before asking the guest of honor to attend. It probably did not occur to him that the President of the United States might have something to do other than attend a Borglum event. He was not even deterred by the fact that Coolidge had repeatedly let it be known he did not wish to make any formal public appearances while on vacation.

Borglum's opening shot was dramatic, romantic, slightly foolish, dangerous and couldn’t have been more ill-timed. He hired Clyde Ice, the famous barnstorming pilot from Spearfish, to fly him over the lodge at low altitude; at the appropriate moment Borglum pitched a large flower wreath from the open cockpit onto the lawn. "Greetings from Mount Rushmore to Mount Coolidge!" announced the card that accompanied this sky borne bouquet.

Unfortunately, it wasn't the ideal time. President Coolidge had summoned General Leonard Wood, governor-general of the Philippines, to South Dakota for consultations. At the very moment Borglum came roaring overhead the general and his commander-in- chief were seated on the verandah discussing the possibility that an insurrection could flare up in the islands. History has not recorded Coolidge's reaction, though it is unlikely the strait-laced president appreciated being bombed with flowers during an important meeting.

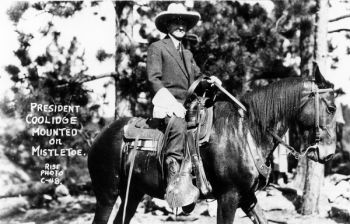

Coolidge eventually consented to attend the dedication ceremony. The last mile up to Rushmore at the time was little more than a muddy trail, and on the day of the ceremony one of the autos became impossibly stuck, blocking the way. President Coolidge was forced to use alternate transportation, and so, wearing a business suit, a 10-gallon cowboy hat and fringed, white leather gloves, he arrived for the ceremony on horseback. The assembled citizens loved it, as did their president.

Silent Cal and Grace left town a month later, with rather less ceremony than when they arrived. As it turned out, the single biggest news of the summer turned out to be something Coolidge decided not to do. Around 30 newspaper reporters comprised the White House press corps, and by Aug. 2 they were frankly bored with Rapid City. When Coolidge invited them all into his office, their curiosity was aroused. As soon as they were all present Coolidge handed each of them a slip of paper, on which was typed a single line. "I do not choose to run for president in nineteen twenty-eight." For a moment the group was shocked into silence. No one in the entire country had expected such an announcement. Finally someone asked the President of the United States if he had anything else to add.

"No," he replied. And having said that, he left.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 1996 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments

they would be there to see him go by. Of course the secret service found them but the only thing said to them was, "You girls will have to back up a bit, the President is coming by in a few minutes" Also Josephine had to move out of the Game Lodge where she was staying while teaching the school that used to be in the little nook close by The president and family were to have the whole Game Lodge. The President and his wife attended the little Hermosa Congregational church every Sunday of their Black Hills stay. A student minister from a Chicago seminary was the man of the pulpit that summer and had no knowledge that he would have the President in his congregation all summer. One man of the congregation thought the young preacher needed a better suit, so promptly took him to Rapid City and bought one. The three seats in second row of plywood-bent-back seating in the church was festooned with red, white, and blue ribbons for the occasion and were left there until we were given pews in the 1960's The middle seat was always reserved for the Coolidge child who had died at a young age.

Where might we find more pictures of the dedication?