The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Faith in the Voters

South Dakota voters have enacted dozens of laws at the ballot box and challenged many more since we became the first state to adopt the initiative and referendum in 1898. We’ve nixed the inheritance tax, banned corporate hog farms, okayed a Right to Work law and said “no” to moving the University of South Dakota from Vermillion to Sioux Falls (7 percent favored the latter). Plus we’ve passed term limits, family farm acts and daylight savings time.

Some state lawmakers find the process insulting — even embarrassing — when their laws are referred and defeated by unelected common folk. Business lobbyists would clearly prefer to argue their positions in the halls of the state capitol than in 66 counties. But citizens and grassroots organizations — including some who can’t afford to send a lobbyist to Pierre — have won major victories because they collected thousands of signatures and took their ideas straight to the people.

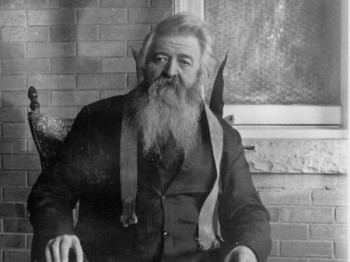

November-style democracy was the inspiration of a feisty Catholic priest who harbored a healthy distrust of institutions and politicians. An Aberdeen fixture for a third of a century, Father Robert Haire played controversial roles in many important territorial and early statehood events. On his 70th birthday in 1915, an Aberdeen newspaper published a tribute to the pastor who was once called the Terror of all Evil-Doers: “A quarter of a century ago, Haire was one of the best loved and best hated men in the community, this because he was a pathfinder. Today, everybody loves him and looks up to him.”

Robert Haire was born in Freedom, Michigan, in 1845. His Irish Presbyterian parents named him Robert Emmet Haire after the Irish rebel Robert Emmet. As a young man he taught in a rural school near Flint and boarded with an Irish Catholic family. Inspired by their devotion, he converted to Catholicism in 1865 and later entered the seminary. He then changed his middle name to William because there’s never been a Saint Emmet. Ordained in 1874, Haire returned to Flint and developed a westward itch along with many of his parishioners. Hearing stories of prosperity in Brown County, Dakota Territory, they headed west, arriving on June 26, 1880. Haire celebrated Mass the very next day in a sod shanty. He filed a claim near Columbia and began plans for Brown County’s first Catholic church, an 18 by 45 foot sod structure.

Shortly after arriving, Haire went to Watertown to prove his claim. On July 4, 1880, he celebrated Mass in the Watertown courthouse and then stepped outside to deliver a rousing Independence Day speech, revealing his twin passions for God and country to his new neighbors.

Haire offered his services to Dakota’s pioneer bishop, Martin Marty, thus beginning a long and tense relationship. Marty assigned him a large territory running from the Minnesota border to the Missouri River and from Huron to what became the North Dakota border. Haire traveled on foot, horse, buggy, and train, celebrating Masses in homes, hotels, and railroad cars. He visited 40 to 50 stations and built churches in several communities. He took up temporary residence in Aberdeen’s Sherman House, which he referred to as “a lighthouse on the coast of hell.” His Masses in the Sherman House dining room sometimes drew as many as 150 worshippers.

In the winter of 1881-82, Haire’s sod church in Columbia caved in, so he looked to build again. That spring, the city of Aberdeen raised money to build a church but the Presbyterian minister was the first to apply so he won the funds. When Haire launched his own building campaign, both Catholics and non-Catholics donated land and money. He dedicated the new Sacred Heart Church on December 26, 1882 (the Presbyterian church wasn’t dedicated until 1883).

In 1886, Haire invited the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Fargo to help him establish a school in the church. A year later, they launched an effort to build a freestanding school. Haire helped haul lumber during the construction. The three-story Presentation Academy of the Sacred Heart opened in 1888.

Haire also recruited the Knights of Labor, a national organization made up mostly of Catholics. The Knights of Labor was viewed with suspicion by the Church hierarchy until Pope Leo XIII gave his approval. Eventually Haire became the Knights’ state leader and newspaper editor. His early political activism also included the Dakota Farmers Alliance, formed in reaction to farmers’ sense of mistreatment at the hands of politicians, corporations and railroads. As Dakota Territory moved toward statehood (Haire was a delegate to a statehood convention), the Alliance attacked Gov. Arthur Mellette for being too friendly with the railroads. Still, Mellette later appointed Haire to the state board of charities and corrections.

Haire helped form the Alliance’s political wing, the Independent Party. Eventually becoming the Populist Party, it focused on regulating railroads, coinage of silver, and democratic reforms like the initiative and referendum. Haire is considered the originator of the American initiative and referendum process; he advocated for the idea several years before it became part of the Populist Party platform in 1890.

His political philosophy and his distrust of politicians led to his desire to create a way for people to propose laws without interference by elected representatives. He laid out his thoughts in an 1891 issue of the Dakota Ruralist: “These men make the laws to suit themselves — are a law to themselves. The people seldom get any law passed they want.”

Plutocrats resisted his proposal and he quickly refuted their arguments. “Of course, the entire plutocracy, given over to fleecing the values that labor produces, are afraid of the people,” Haire contended. “Such fellows will jump on any proposition with both feet when it is proposed to give the law-making power into the hands of the electors.” Nonetheless, “the people are capable of feeling for, giving form to, and finally decreeing their own laws.”

He described his program that would replace the legislature with a system for popularly proposed legislation: “any law that has been demanded by 25 percent or more of the precincts of the state shall be drafted and printed,” and distributed statewide. On the first Monday after the fourth of July, “the electors in their several precincts, shall either confirm or reject said law, using the Australian voting system. If a law passes, it is law. If it does not get a majority of the whole state electorate, it is no law.”

It wasn’t until 1898, during the re-election of South Dakota’s only Populist governor, Andrew E. Lee, that the initiative and referendum appeared on the state ballot as a constitutional amendment. The amendment passed easily, making South Dakota the first state in the nation to give voters such power.

"...Haire was one of the best loved and hated men in the community, this because he was a pathfinder."

The initiative and referendum has become common in American democracy. Twenty-six other states have adopted one or both procedures. Since the first use of the initiative in Oregon in 1904, voters across the United States have considered about 2,300 statewide initiatives, approving 41 percent.

Despite the relatively infrequent use of initiatives in South Dakota, critics charge that it’s too easy to get issues on the ballot. By law, petitioners must collect signatures from 5 percent of the voters in the last gubernatorial election. Gov. Peter Norbeck raised the concern as early as 1917, but legislative efforts to increase the number of signatures needed to put a measure on the ballot have been rejected in statewide elections. During one legislative session, a proposal that would have required the requisite signatures from at least 33 counties was defeated when arguments arose over the “one-man, one-vote” principle. Shouldn’t two signatures from Mitchell count just as well as a signature from Eureka and another from Ipswich?

David Owen of Sioux Falls, president of the South Dakota Chamber of Commerce and Industry, has worked to both support and defeat ballot initiatives. He believes the process needs “respectful reform” and he lobbied successfully in the 2009 legislative session for several changes. Owen believes South Dakotans like the grassroots initiative process but he also thinks they’re put off by the “commercialization” that’s developed around the process, in which consultants and signature-gathering firms sell their services to interest groups.

Before the initiative and referendum were approved, Haire served on the Board of Regents during some tumultuous years. Gov. Lee thought there were enough colleges in the state, but Haire believed at least one more was needed in Aberdeen. The governor vetoed the first attempt to create a “normal school” there, but later acquiesced. Northern Normal and Industrial School opened in 1901, and Haire received much credit. A memorial to him stands on the Northern State University campus, a rare tribute to a man of the cloth on a public campus.

By the time the college was formed, however, he wasn’t exactly a man of the cloth. Years earlier, his activism had put him in conflict with Bishop Marty. One of Haire’s earliest causes was temperance. He spoke around the state in support of a prohibition clause in the state constitution. While Bishop Marty shared Haire’s disdain for alcohol, he preferred to leave state regulation out of it. Others also disagreed with Haire. In 1888, the Aberdeen News reported that some of his parishioners were petitioning to get him removed, noting that, “this attack was conceived in the late Brewers convention in St. Paul.” Haire confronted them directly. During a Sunday mass, he asked those present who supported him to stand. The “congregation rose en masse.”

Haire was perhaps more directly antagonizing to his bishop when he launched Dakota’s first Catholic newspaper, the Dakota Catholic American. In the first issue in 1887, editor Haire wrote: “In politics we will be strictly non-partisan. In religion we will be what our name indicates. In economic measures we will be for the right. We have the approbation of our good father, Our Bishop Marty. Thus fortified, we cannot fail.” The good father’s approbation failed rather quickly. Future issues betrayed Haire’s politics, and Bishop Marty shut the paper down in November 1888.

Haire’s progressively radical politics probably sealed his fate. The Aberdeen News reported on a lecture he gave in 1888:

[Fr. Haire] emphatically declar[ed] that the time had come when the laboring masses would have possession, and if this could not be secured in any other way a bloody rebellion would certainly be the result. He said, also, that he was getting very tired of this representative form of government, but hoped with all his heart for the time to come when the old Puritan democracy principles would rule the nation; when the laws would be framed by the people themselves and not by a few pinheads and trading representatives of the Vanderbilt-Gould type.

Bishop Marty soon traveled to Aberdeen and ordered Haire transferred to Wakonda in southeast South Dakota. When Haire declined the bishop dismissed him. He remained a priest, but could no longer serve as a parish pastor or administer sacraments.

Haire’s punishment weighed heavily on him. He later told a friend, “Do you know what has kept me in the church in spite of my exceeding bitterness against the bishop? It is the Blessed Sacrament. When I kneel before the altar, I seem to hear a whisper, ‘Stay a little longer. All will be well.’ And so I hang on in spite of everything.”

In religious exile, Haire grew more involved in politics. He took an active part in the Fusion Party, the coalition of Populists, Democrats, and Silver Republicans (Republicans who left their party to support coinage of silver) that elected Gov. Lee in 1896. Soon thereafter, however, Haire saw the coalition fragmenting and vented his disappointment. In speeches at Fusion Party meetings in 1898, he alternately raged at his comrades and called for harmony

Eventually, however, Haire began to step away from the state stage. He was a Socialist presidential elector in 1900, and in 1902, the Socialists nominated him for the U.S. Senate. Otherwise he seemed to be more interested in his local Socialist meetings, where he was recognized as a mentor according to a tribute published by the South Dakota Socialist Party after his death: “During the earlier years of the organization, he seldom missed a meeting, always taking a leading part, but gradually teaching us to think and speak for ourselves. Later on, he would take no part unless we seemed to be drifting from Marxian principles when he would set us right.”

Despite Haire’s challenges and successes in public affairs, there was a hole in his life. When Bishop Thomas O’Gorman replaced Bishop Marty, Haire submitted his case for reinstatement. O’Gorman asked Haire to make a 30-day retreat and a confession. When Haire complied in 1902, the bishop assigned him as chaplain to the Presentation Sisters and their new St. Luke’s Hospital in Aberdeen. He served there for the remainder of his life.

In January 1916 he wrote to his brother, “My own health is on the down grade, yet no grippe.” On March 4, 1916, he celebrated Mass and then went to his room. He fell ill and reportedly called for a local Baptist minister who had been a Socialist comrade, but the friend arrived too late.

Bishop O’Gorman presided at the funeral in the Sacred Heart Church that Haire had built three decades earlier. Both former Gov. Lee and Socialist leader Eugene Debs sent notes. Debs wrote, “Father Haire was a true follower of the Judean Carpenter. He gave all he had, and best of all, he gave himself to the poor. But he not only sympathized with the poor, he told them why they were poor and how they might put an end to their poverty.”

A newspaper profile after Haire’s death related a telling story. Haire and a parishioner were approached on an Aberdeen street by a vagrant who successfully solicited a dollar from the pastor. The parishioner scolded, “That bum’ll probably get drunk on your dollar.” Haire replied, “Let’s give the poor fellow the benefit of the doubt. If he was indeed hungry — and I believe he was — how would I have squared myself with the Giver of all good things had I refused him?”

A few months after Haire’s death, Bishop O’Gorman penned a fitting epitaph: “He had been in earlier years, when the State was still in the pioneer stage, a most zealous missionary. I believe that the last ten peaceful years of his life and his happy death were rewards of the good and fruitful work of the early years.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2009 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.