The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

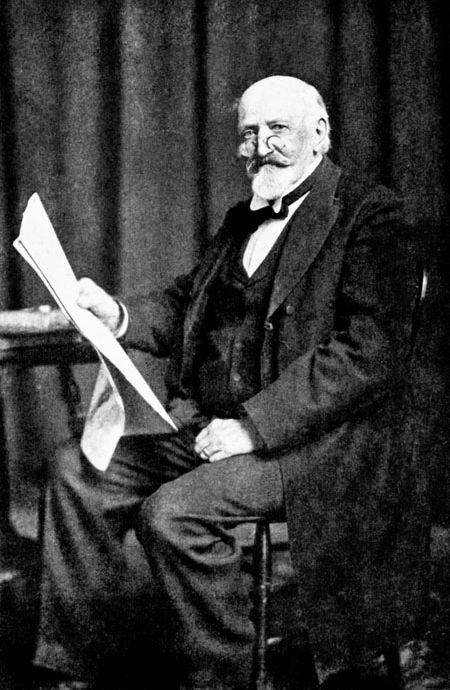

George Kingsbury: Eyewitness to History

|

| George Kingsbury is considered the Father of Journalism in South Dakota. He published the Yankton Press and Dakotan for 40 years and authored the impressive History of Dakota Territory. |

George Washington Kingsbury stepped off the Marsh & Rustin stagecoach at Yankton, Dakota Territory, on March 17, 1862. The muddy little river town was then only three years old. Kingsbury, a journeyman printer, planned to work there for a few months, then return home to Kansas and get on with his life.

Things didn’t work out quite that way.

Kingsbury arrived at a historic moment. Gov. William Jayne had that very day convened Dakota’s first legislature in the rude settlement’s log-walled Episcopal church; its members were charged to lay the foundation of, “a government that would endure for all time,” Kingsbury wrote in his History of Dakota Territory. “[Their] duty was a sacred one.”

Which the delegates put off until they’d done a lot of logrolling and selected a permanent capital city. Vermillion and Yankton were the main contenders, but the latter’s supporters thought they had things buttoned up thanks to a back-channel bargain. They supported John Shober and George Pinney for council president and Speaker of the House; in return, the pair from Bon Homme was supposed to back Yankton’s bid.

Pinney was a man of no small ability, “the peer of any other member,” wrote Kingsbury, but he was also an inveterate schemer and “inclined to be erratic.” His fellow legislators watched him, “with constant apprehension of mischief ... a harmless motion to adjourn from him would be accepted by half the members as portending a plot.” Pinney was elected Speaker, then promptly reneged on his deal with the Yankton delegation; he didn’t stay bought, as historian Doane Robinson put it, which set off days of parliamentary wrangling.

Excitement was “at a fever-heat” and spectators thronged the lobby when the capital bill came up for consideration, wrote Kingsbury. Suddenly, troops of the Dakota Cavalry, with bayonets fixed, marched into the legislative chamber and surrounded the Speaker’s podium. Pinney had secretly asked Gov. Jayne to dispatch the soldiers, either to quash a rumored conspiracy to have him replaced as Speaker or as part of a convoluted intrigue to embarrass the governor, but all the maneuver did was “arouse great indignation” among the membership. They demanded an explanation and Pinney’s scheme “went to pieces in an hour.”

Pinney was forced to resign and Yankton won the prize, but settling the matter didn’t calm the waters. John Boyle of Vermillion and Enos Stutsman of Yankton “had some hot words” over dinner at the Ash Hotel, wrote Kingsbury, and matters soon escalated. “Boyle seized the ketchup bottle and flung it at Stutsman’s head, narrowly missing him. ‘Stuts’ retaliated with a fusillade of tumblers, cups and the skeleton of a fowl that had contributed to the feast. The combatants then flung themselves ... across the table for a finish fight,” that might have resulted in serious injuries had not friends of the two men intervened.

Lawmaking on the frontier was proving to be a less than genteel affair, which did not come as a surprise to the delegates. Jim Somers, the House of Representatives’ Sergeant-at-Arms, was a burly ex-lumberjack with a violent streak; he later shot a sheriff and was himself killed in a shootout near Chamberlain. This preference for solving problems with his fists or worse was common knowledge before he was appointed; the legislators apparently considered this a recommendation for the job of keeping order in the House.

Somers and a group of lawmakers were drinking one evening in Antoine Robeare’s saloon, the legislature’s second home, when Pinney came in the front door. “Suddenly the window … flew up and Speaker Pinney popped out,” wrote Kingsbury. Somers appeared at the window, grinning, as another legislator and Robeare took after the fleeing Pinney — a chase that ended when the ex-speaker drew a pistol and his pursuers’ “belligerent ardor moderated.”

By the time the legislative session ended in May the members had managed to discharge their sacred duty despite all the side shows. Kingsbury, meanwhile, reconsidered his plans. Like many a young man in those years, he had headed west in search of adventure and opportunity. He found both in Yankton. There was no need to look any farther.

*****

George W. Kingsbury was born in 1837, on a farm in upstate New York. He learned the printing trade as an apprentice at the Utica Daily Evening Telegraph, but at age 18, “[he] removed to Wisconsin to work with civil engineers on the Watertown & Madison Railroad,” wrote Kingsbury in an autobiographical sketch he penned for History of Dakota Territory. When the Panic of 1857 brought construction on that line to a halt he drifted west, from newspaper to newspaper, eventually reaching Leavenworth, Kansas Territory.

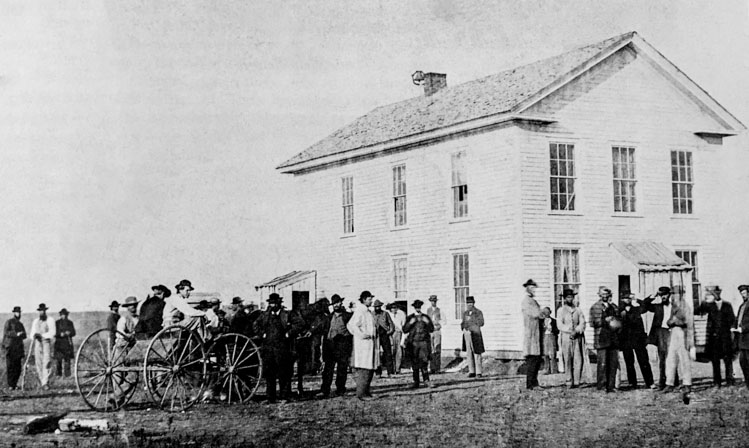

|

| The Territorial Capitol at Yankton, photographed in the early 1860s. |

Fort Leavenworth was a staging point for army supply trains on the Santa Fe Trail in the late 1850s. Kingsbury decided this made for an opportunity, “to see the western country at government expense by signing on as a driver,” a plan he soon laid aside after he saw how much grueling work it took to yoke a dozen oxen to each wagon, never mind manhandle it across the prairie. He returned to town and found a position with the Leavenworth Daily Ledger.

Kansas entered the Union in 1861, and opportunity drew Kingsbury to Topeka, the new state’s capital. There he met Josiah Trask, who had parlayed his political connections into a contract as the official public printer for both Kansas and Dakota Territory, which came into being in March of that year. Trask hired Kingsbury to do the actual printing work in Dakota while he stayed in Kansas, a decision that had tragic consequences for him. Trask, a man of strong abolitionist beliefs, was among those killed when the infamous Confederate raider William Quantrill attacked Lawrence, Kansas, a hotbed of the anti-slavery cause.

Kingsbury had been in Dakota barely two months before he went from itinerant printer to publisher and co-owner of the Weekly Dakotian. Frank Ziebach and William Freney had started the paper in 1861 to help a third partner, Capt. John Todd, become the first territorial delegate; once Todd was elected, the Dakotian faded away. By the time Ziebach and Kingsbury revived what had been a Democratic paper the territory’s political winds had shifted, wrote Kingsbury, “and prudence suggested the formation of the partnership [in the name of Kingsbury], a Republican.”

Thus began what historian Bob Karolevitz called “a game of journalistic musical chairs” that went on for years. Newspapers in Yankton combined and split, opened and folded and opened again with different owners; opponents in one election cycle might be partners in the next. Kingsbury’s tenure at the Weekly Dakotian lasted until he fell out with Dr. Walter Burleigh, who had purchased a piece of the paper to promote his campaign for territorial delegate. Kingsbury and Moses K. Armstrong then started a new publication, the Dakota Union, and “fought a glorious fight” against the good doctor, as an admirer put it. Burleigh, the resident Indian agent who set a standard for corruption that was never bettered in Dakota, triumphed despite their opposition, and in the election’s wake the two warring newspapers merged to form the Union and Dakotaian.

Toward the end of his first decade in Dakota, Kingsbury purchased a state-of-the-art steam-powered press, the first in Dakota Territory, and used it to churn out the news under various banners. In 1875 he founded the Black Hiller, aimed at the gold seekers flooding into town. It proved so financially successful that it enabled Kingsbury and Wheeler Bowen to begin publishing the Press & Dakotaian, a daily newspaper that first appeared on April 26 of that year and is still publishing five editions a week in an era when many small daily papers have turned off their presses and closed their doors.

*****

George Kingsbury wrote hundreds of thousands of words in his career, but next to nothing about his personal life. His autobiographical sketch in History of Dakota Territory is sparse and devoid of any sense of the man. “On the 20th of September, 1864,” he wrote, “George W. Kingsbury, of Yankton, and Lydia Maria Stone, daughter of Nathan and Laura Stone, of Lawrence, Kansas, were married at the home of the bride’s mother.”

Lydia and George returned to Yankton and settled down to raise three sons, George, Theodore and Charles. Lydia’s passing evoked the only morsel of emotion in the essay, and that sounded oddly stilted: “Lydia, the wife and mother, died February 1, 1898, and after a few years the little family was broken up, the home practically abandoned.”

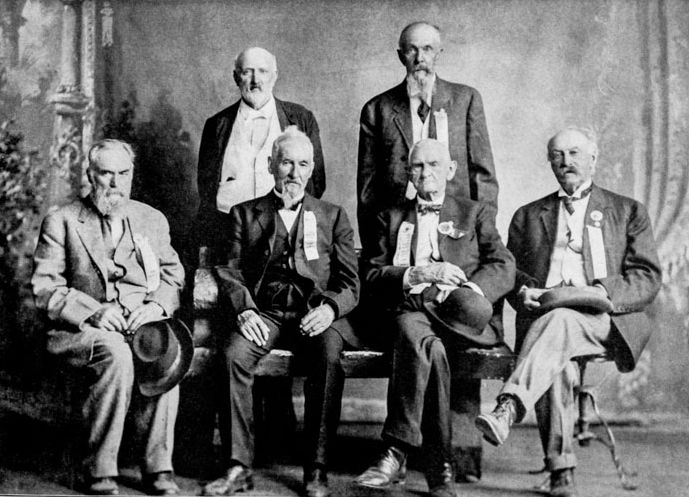

|

| George Kingsbury (back row, left) was honored as a pioneer of Dakota Territory during its 50th anniversary in 1911. Other honorees included C.J. Holman (back right) and (front row, from left) Horace Bailey, John Shober, William Jayne and Joseph Hanson. |

Kingsbury spent 40 years as a newspaperman in Yankton, which afforded him a front row seat as the territory’s history unfolded, but he was more than an observer. When the territorial legislature convened for its second session in 1863 Kingsbury took a seat in the upper house as a delegate from Yankton, one of many public and private offices he held through the years. He sat on Yankton’s first city commission, was secretary of the corporation that launched the Dakota Southern Railroad and served as the territory’s assessor of internal revenue; he also captained one of Yankton’s two polo teams and produced a traveling play, “The Chaperones.”

When statehood arrived in 1889 Kingsbury served a term in the new legislature and was later appointed to the State Board of Charities and Corrections by Gov. Andrew Lee. On the journalism front, he found himself covering a familiar story. South Dakota’s voters were to select a new capital in the first statewide election of 1890, and the contending cities’ tactics often landed “within the boundaries of criminality,” the old-timer wrote. “[Their] unbecoming and disgraceful conduct cast a shadow upon the fair name and fame of the young state.”

Kingsbury sold his publishing interests in 1902 and began work on History of Dakota Territory, a project he was uniquely qualified to undertake. Modern readers may find fault with some of Kingsbury’s attitudes, his absolute belief in the superiority of white culture over that of the indigenous “savages” among them, but none can say he didn’t do a thorough job. History’s five ponderous volumes, bursting with original documents and encyclopedic detail, dealing with every major and many minor matters of the era, constitute an invaluable resource. Scholars and students of history alike are in his debt.

*****

Yankton’s business community had dreamed of a bridge across the Missouri River since the settlement’s earliest days, the better to draw trade from Nebraska. Financial and technical problems sidelined various schemes through the years; in the meantime, a ferry launched in 1870, and a pontoon bridge followed 20 years after that. This had to be dismantled and reassembled twice a year, however, so it was clearly only a stopgap measure.

Kingsbury had seen a number of bridge schemes up close over the years, and he was on hand when one finally succeeded in spanning the Missouri. E.J. Dowling and an informal group of Yankton’s leading citizens known as the Monday Evening Club resolved that the only way to ensure a bridge was built was to build it themselves. “Their spirit served as midwife to the project,” wrote Kingsbury in a special edition of his newspaper published when steel reached Nebraska.

When the Meridian Highway Bridge formally opened on October 11, 1924, the 87-year-old George Kingsbury rode across as an honored pioneer. It was one of his last public appearances. He grew more and more feeble and slipped away on January 28, 1925, leaving a legacy in South Dakota history and journalism that few scribes will ever match.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments