The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Golden Oldies

|

| Donus Roberts, pictured in his Watertown bookstore, coached speech and debate for 39 years at Watertown High School. |

Search online for books about South Dakota and Barnes and Noble yields nearly 3,000 results. Amazon returns 30,000. Google produces 30 million. With so many books to read about your favorite state, how do you select the titles that best explain South Dakota and its people?

We’ve narrowed your choices down to about a dozen with help from Watertown bibliophile Donus Roberts. Roberts retired in 1999 from Watertown High School, where he spent 39 years as an English teacher and became one of the most highly decorated debate coaches in the nation. He is a man who loves words and ideas. He’s also an avid book collector, amassing over 15,000 titles in his personal collection and offering another 18,000 for sale at his shop in the East Point Plaza on Highway 81 and online.

Do not feel limited by Roberts’ list. Hundreds of authors have told South Dakota’s story in their own way, and their books are worth reading, but Roberts calls these “the golden oldies.” Some titles are available in bookstores or online, but others are out of print. Check each book’s availability at your local library.

Robert Karolevitz

Challenge: The South Dakota Story

|

Robert Karolevitz was one of South Dakota’s most prolific authors. He wrote 37 books and thousands of magazine articles and newspapers columns from his home at Mission Hill, northeast of Yankton. He enjoyed poking fun at himself, and was known for his sense of humor (evidenced in books called Everything’s Green But My Thumb, and Toulouse the Goose, a collection of off-the-wall columns). But Karolevitz also wrote histories of Yankton, the Catholic church in South Dakota, newspapering, Douglas County and a biography of Harvey Dunn. Roberts believes Karolevitz’s most lasting contribution is Challenge: The South Dakota Story.

“There are no comprehensive histories of the state that have been written in recent times,” Roberts says. “All of our histories were written some time ago. I think it’s one of the best interpretations of a state because it’s not sequential. It’s more thematic.”

Challenge, published in 1975, is one of the few histories written by a native South Dakotan. Karolevitz was born at Yankton in 1922 and lived all but 15 years of his life in Yankton County. His book describes 10 challenges people faced in settling and living here: conflicting cultures, the Missouri River, gold, Wounded Knee and the Dirty Thirties are among them.

Karolevitz struggled to identify his audience and the book’s organization. Challenge was originally intended for use as a junior high level textbook, but he adapted it for all ages. He also selected a topical rather than chronological approach “to emphasize and expand the why as well as the what of the unfolding saga,” Karolevitz wrote in the book’s introduction. “This labor of love is offered with the hope that it will generate native pride in The Challenge State and provide a realistic textbook for studying the heritage of a bountiful land — where the bounty is seldom attained without a struggle.”

Ole Rølvaag

Giants in the Earth

|

Ole Rølvaag’s classic Giants in the Earth, an enduring tale of Norwegian immigrants trying to conquer the Plains, follows Per Hansa and his wife Beret as they homestead in eastern South Dakota in the 1870s. They encounter drought, grasshoppers and blinding blizzards that bring tragedy. “It’s not only one of the great frontier novels,” Roberts says. “It belongs in the top rank of novels written in America. If you want to be well read about the Upper Midwest, Giants in the Earth is a must read.”

But had Rølvaag listened to his father, Giants in the Earth, published in 1927, may have remained a seed in his imagination. Rølvaag was born in 1876 on a small island of the northern coast of Norway. He walked 14 miles round trip over rocks and moors to attend school, but he was forced to stop at age 14. “His father finally told him he was not worth educating,” wrote Lincoln Colcord, Rølvaag’s colleague who helped translate the novel from Norwegian to English.

Rølvaag embarked on a life of fishing, but he became a voracious reader. He spent two days traveling by foot to a nearby village just to get a copy of Ivanhoe. He dreamt of writing a novel as early as age 11, but never seriously embarked on a project until he attended school in South Dakota 15 years later.

Rather than spend his life as a fisherman, Rølvaag asked an uncle living in South Dakota for help getting to America. One day a ticket arrived, and Rølvaag spent three years farming near Elk Point. Friends urged him to attend school, but his father’s admonition still rang clearly in his head. Still, Rølvaag wanted a life of farming even less than fishing, so in 1899 he enrolled at Augustana Academy in Canton.

He quickly discovered that he felt most comfortable in school. After graduation he attended St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn., and eventually became the school’s professor of Norwegian studies. His sequel to Giants in the Earth, called Peder Victorious, appeared in 1929. He died in 1931.

Doane Robinson

Brief History of South Dakota

|

Plenty of histories have been written since Doane Robinson’s Brief History of South Dakota was published in 1905, but that doesn’t mean you should discount his volume. “It’s still very much worth reading because so much of the history written in that period of time was fairly slanted when it came to the Native Americans and whites,” Roberts says. “But Robinson was more objective than most writing at the time.”

The history of a place grows with each passing day. By modern standards, the majority of our state’s history occurred after Robinson’s book appeared. But that may be the secret to its appeal. Robinson’s book focuses heavily on the region’s early history: Lewis and Clark’s expedition up the Missouri River, the rise of the fur trade, the gold boom in the Black Hills and the quest for statehood. Robinson also devoted full chapters to Sam Brown, who rode 150 miles on horseback through a blizzard to avert a battle with Indians, and the horrid winter of 1880-81.

Robinson was born in Sparta, Wisc., in 1856. He farmed in Minnesota, then moved to Watertown to practice law. He developed a strong interest in state history and became secretary of the state historical society. In addition to his Brief History, Robinson was a poet and also founded the Monthly South Dakotan, the first magazine to explore the history and culture of the state.

If Robinson’s literary legacy lies in his Brief History, his greatest overall contribution was growing the idea of Mount Rushmore. Inspired by Gutzon Borglum’s sculpture of Confederate soldiers at Stone Mountain, Georgia, Robinson originally envisioned figured carved into the Needles, but eventually settled on the heads of four famous leaders chiseled into the granite of Mount Rushmore.

After retiring as secretary of the state historical society, Robinson returned to farming near Pierre. He died in 1946 at age 90.

John Milton

South Dakota: A Bicentennial History

|

When New York publishing giant W.W. Norton embarked upon its States and the Nation Series commemorating the country’s bicentennial in 1976, editors asked John Milton to write South Dakota’s volume. Milton, an English professor at the University of South Dakota since 1963, was quickly gaining a national following for his short stories and fiction, and for establishing and editing South Dakota Review, the state’s literary journal and “a massive contribution,” Roberts says. Milton expressed reservations about writing a history of South Dakota, but colleagues “gave me a strong nudge when I was reluctant to take on this project,” he writes in the book’s preface. His 200-page volume became one of the state’s classic histories. “I know it was considered to be one of the best in that entire series,” Roberts says. “You don’t find him in it. It’s very factual, though he tends to stay away from the cultural issues that have divided us over the course of time.”

Milton’s background as a storyteller aided his treatment of South Dakota. His book is organized topically and reads like a novel. And his approach differed from other historians. “My concern is with the portrait, with the spirit of the place and of the people, who either visited it or settled down on it, making this particular place their home,” Milton wrote.

Herbert Krause

Wind Without Water, The Thresher and The Oxcart Trail

|

Herbert Krause penned just three novels during his 32-year career as a teacher and writer in residence at Augustana College, but Roberts includes all of them among his must reads for South Dakotans. Wind Without Water, The Thresher and The Oxcart Trail all describe the trials of farming the Plains 100 years ago.

“There’s no more realistic treatment of the way it was out here in the early 20th century,” Roberts says. “The frustrating part is that Krause just isn’t read today. Nobody reprints the trilogy. He became a more modern version of Hamlin Garland. No one has ever written farming like he did. People from this state are missing something if they don’t search him out.”

Krause was raised north of Fergus Falls, Minn. He developed a love of the written word at a young age, much to the chagrin of his blacksmith father. When young Krause begged for, and finally received, an issue of Cosmopolitan magazine, his father told him, “Well, son, you'd have done better getting a pair of socks.”

Krause’s admiration for Ole Rolvaag led to his enrollment at St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn., although they never met because Professor Rolvaag died shortly after Krause arrived on campus. Krause longed to write of German homesteaders as Rolvaag had written about Norwegians. When Wind Without Rain appeared in 1939, critics immediately compared Krause to Rolvaag and eventually declared him to have surpassed his idol in Plains literature.

Newspapers in New York and Chicago heralded Wind Without Rain as national bestsellers. The book follows the Vildvogel family struggling to survive on the land of western Minnesota. The Thresher (1946) tells the story of Johnny Black, who hides personal pain behind his dominant steam-threshing rig in North and South Dakota. The Oxcart Trail (1954) is a love story rich with historical detail set along the trails that ran from northern Minnesota across the Dakotas to the Pacific Northwest in the 1850s and 1860s.

Krause was also a prolific poet and wrote articles about the customs of the Upper Midwest and ornithology. In 1970, he founded the Center for Western Studies. Krause died in 1976.

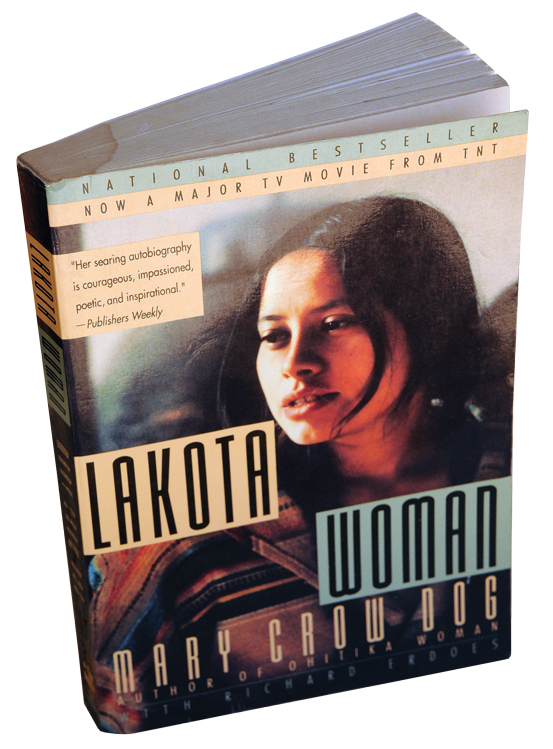

Mary Crow Dog

Lakota Woman

|

Roberts selected Lakota Woman by Mary Crow Dog because, he says, “It’s got some of the great lines I’ve ever seen in a book.” And you don’t have to read far into the book to find an example. “I am Mary Brave Bird,” she writes in the book’s opening chapter. “After I had my baby during the siege of Wounded Knee they gave me a special name – Ohitika Kin, Brave Woman, and fastened an eagle plume in my hair, singing brave-heart songs for me. I am a woman of the Red Nation, a Sioux woman. That is not easy.

“I had my first baby during a firefight, with the bullets crashing through one wall and coming out through the other. When my newborn was only a day old and the marshals really opened up on us, I wrapped him up in a blanket and ran for it. We had to hit the dirt a couple of times, I shielding the baby with my body, praying, ‘It’s all right if I die, but please let him live.’”

“That’s one hell of an opening,” Roberts says.

Lakota Woman was published in 1991 and immediately became a national bestseller. It won the 1991 American Book Award and became a television movie produced by TNT and Jane Fonda in 1994.

The book chronicles Crow Dog’s life until 1977. She was born in 1953 on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. At age 18, impressed by the teachings of medicine man Leonard Crow Dog, she joined the American Indian Movement. Her book is important because it provides a young Indian woman’s perspective on reservation plight, assimilation and racism in western South Dakota. But Crow Dog’s recollection of the Wounded Knee siege is a highlight. “There are no objective reports [of the Wounded Knee occupation],” Roberts says, “but her cry in the wilderness is very good.”

Crow Dog followed Lakota Woman was a sequel entitled Ohitika Woman in 1994. She died in 2013.

Sally Roesch Wagner

Daughters of Dakota

|

When Will Robinson served as state historian, he recognized that only half of South Dakota’s history was being told. “We have a shelf full of ponderous tomes, 32 inches in length with over 10,000 biographies of male South Dakotans,” Robinson lamented in the 1960s. “When it comes to the women who worked alongside the men and frequently made it possible for them to accomplish things which gave them a place in our history, little recognition has been given.”

But women’s history was being recorded thanks to Marie Drew, chair of the Pioneer Daughters Department of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. For 40 years she supervised the gathering of pioneer women’s stories in every state. South Dakota’s intimidating collection of 4,000 to 6,000 stories lay virtually untouched in the state archives until a spring day in 1987, when an archivist persuaded Sally Roesch Wagner to take a break from researching women’s suffrage to peruse the papers.

“My researcher’s eye knew that this was the find of a lifetime,” Wagner later wrote. “Represented was the scope and range of the lives of white women settlers when the land was taken for non-Indian settlement: white and black, rich and poor, native-born and immigrant, representing a spectrum of nationalities, ages, lifestyles and religions.”

Wagner strove to publish a book of stories in time for the South Dakota centenial in 1989. The first volume of Daughters of Dakota appeared that year and was followed by five more through 1994.

“In concentrating upon the women, you also concentrate upon the men, because they had to live this land together, even though it emphasizes the difficulties of women,” Roberts says. “The guys could get out. They’d go down to the river and cut wood, or plant corn and try to grow something. The women were stuck in whatever was the house, and it’s very legitimate to talk about the trials being quite different.”

Frederick Manfred

Lord Grizzly

|

The first time Frederick Manfred heard the legend of Hugh Glass, he knew he would someday write about it. “Hugh’s great wrestle with the grizzly, his desertion by friends, his fabulous crawl, his vengeful chase after the deserters, and its outcome – all these things seized hold of my imagination,” Manfred recalled. “I saw Hugh and his agony. I saw his matted grizzled beard, his flashing grieving eyes, his torn bleeding body, his godlike stubborn manner. I saw all this not with the eye of an historian but with the eye of a novelist.”

Glass was a real mountain man, recruited by fur trader William Ashley in 1822 to travel up the Missouri River to its source and collect furs. Glass’ near fatal encounter with a grizzly bear along the Grand River was real, and so was his 200 mile crawl across West River’s short grass prairie to Fort Kiowa. But Manfred’s Lord Grizzly, published in 1954, is a novel, not a historical account.

For nearly 10 years Manfred immersed himself in the story. His daughter Freya Manfred recalled how her father “researched the novel by crawling around on all fours with one leg bound in a makeshift splint, eating grubs and ants to see how they would have tasted to the book’s hero, old Hugh Glass.”

Manfred was a prolific writer, penning nearly two dozen books inside his tiny writing cabin at his home in Luverne, Minn. He taught briefly at the University of South Dakota and Augustana College and coined the term “Siouxland,” describing the region where South Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa meet.

Lord Grizzly is part of Manfred’s Buckskin Tales series that explores life in the Upper Midwest through the 19th century. It is divided into three parts: the wrestle, the crawl and the showdown. They represent the three components of the Glass story that Manfred found to be the most consistent in various interpretations.

“This book reads extremely well today,” Roberts says. “It’s not at all dated. The adventure is incredible. The crawl is incredible. The entire story of revenge is incredible. He probably deserves more recognition for that than he’s ever gotten. He was very frustrated because he felt that he had done a lot of good work for literature of this region, and mostly people just sort of waved him away.”

O.W. Coursey

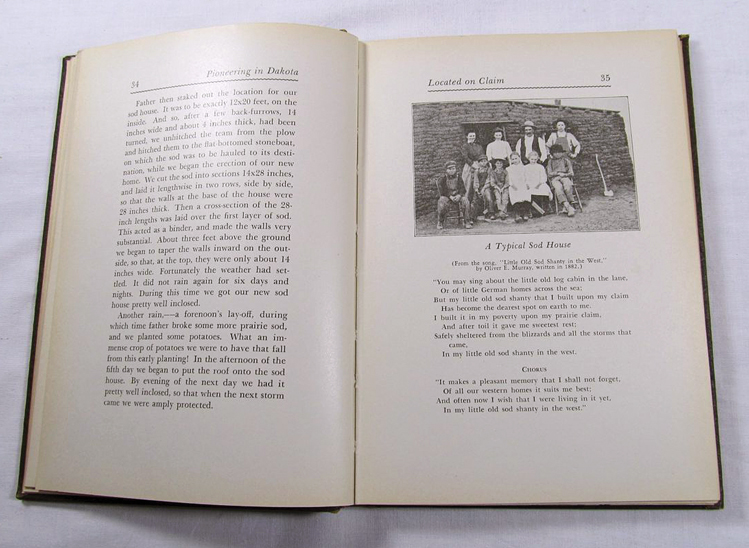

Pioneering in Dakota

|

O.W. Coursey may be the most prolific author that no one remembers. The title page of his short autobiography Pioneering in Dakota lists him as the author of “eight volumes of Biography, four of History, three on Biblical Characters, two of fiction, two on Literature, two of Short Stories, two of Winning Orations (Compiled), one on School Law and one on Ethics.”

Coursey, a writer, teacher and lecturer who operated the Educator Supply Company in Mitchell, chronicled the lives of many early South Dakotans, including Senator Alfred Kittredge and General William Henry Harrison Beadle, but it’s his unique first-hand account of homesteading in South Dakota that’s most worth reading, Roberts says.

“It’s not a comprehensive history. It’s a pioneering history, what it’s like to come to this country and settle,” Roberts says. “He wrote about the pioneer experience, including the first really comprehensive story about the Blizzard of 1888. On his total work, he should be remembered, and Pioneering in South Dakota is probably the best of his work.”

Pioneering in Dakota covers 14 years of Coursey’s life, beginning with his family’s train trip from Illinois to Huron in 1883. Along with his first-person account of the Blizzard of 1888, in which he was trapped in school, his chapters on filing and claiming a homestead, building a sod house, the coming of the railroad (and the fate of towns along the track) and his stories of surviving a tornado and a prairie wildfire provide a unique perspective of life in the late 19th century.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2012 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments