The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

High in the Saddle

Wall’s Galen Wallum paints a vanishing breed

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2000 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Maybe it’s in the water. First the tiny town of Manchester produced South Dakota’s favorite son artist, Harvey Dunn. By age 14, long before he’d heard of his famous predecessor, Wallum was selling paintings at his Uncle Donne’s gas station.

His early years were on a farm a mile south of the little Kingsbury County town. “When I was a kid we raised corn and wheat and sheep and cattle and hogs. We worked seven days a week. I asked my dad for a half day off one time and he had a mouthful of mashed potatoes and it looked like a blizzard.”

When Wallum was 13 the house blew up. The family moved to Wallum Corner, and Galen enrolled in Iroquois High School, which he would eventually finish, “under duress. If I ever get far enough ahead to write a book,” he said, “it will be ‘How Six Years of High School Finally Paid Off.’"

The year the house burned down, Galen’s uncle Deonne encouraged him to start painting. Galen had done a paint-by-numbers he got for Christmas, but decided he could do better on his own. His first medium was barn paint on plywood. “It was latex paint,” he said. “The paintings were kind of crude, but one is still holding up on the tailgate of a junk trailer. At least they dried in a hurry. I could sell them the next day.”

And sell them he did. Deonne Wallum peddled Galen’s first works at the service station for $4.

|

| "I feel I'm painting the last of the old cowboys out there, the real good ones," says Wallum. |

After a year on a helicopter in Vietnam, Wallum was discharged in Oklahoma. There he studied commercial art at Okmulgee Tech, and he’s been a full-time artist ever since.

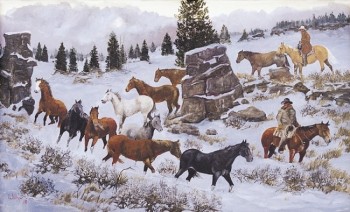

From the beginning Wallum painted what he knew and loved: cowboys and horses and western scenes. “I feel I’m painting the last of the old cowboys out there, the real good ones. They’re vanishing fast. You don’t see real cowboys much anymore. Cowboys these days may be riding four-wheelers.”

He found a market for his work at shows in Arizona. And there he met a woman who “showed me more in three days than I ever learned in art school,” technical details like variations in brushes and how to mix paints. He’s worked with oils ever since.

For a while he sold most of his work in Arizona, but two galleries went broke and his paintings disappeared. By then he had connections to sell more of his work to private collectors.

For 17 years Wallum painted on his ranch south of Tulsa. Then in 1991 his wife died of cancer, and he brought their two younger daughters home to South Dakota because he thought this would be a better place for them. Lured to the majesty of the Badlands, they settled in Wall. Both girls worked as teenagers at Wall Drug.

Galen never lived again at Wallum Corner, but he did transport parts of Wallum Corner to Wall. He tore down the old corrals and hauled the lumber home to recycle as frames for paintings and paneling for his studios.

Now that the girls are grown, friends are tugging Wallum one way and another, he said, to Arizona or Montana. But he wants to stay in western South Dakota, because that’s where he finds the people he needs to paint. And except on occasional commissions, he restricts himself to depicting cowboy life.

“I stay away from painting Indians and cavalry and mountain men,” he said. “There’s a thousand things you can paint in cowboy life. The old-style cowboy was always on the move. He works on one ranch awhile, and maybe he has a little falling out and he moves on up the line, but maybe later they’ll need him back there again. The old cowboy is a different breed.”

Wallum knows first-hand the life he paints. “We always had cows and horses when I was growing up, so I just picked it up. These old guys are a lot better than me, but I’m a fair horseman and cowboy. When they get short-handed they still call me up.” Shaggy mustache and sunburnt hide, Wallum looks the part. With a coat of dust on his black felt hat and a little manure on his boots, he would blend in with the old timers.

Besides roping and painting ropers, Wallum invented a practice roper. “The bugs are finally out of it,” he said. “It’s made of square tubing. You sit on it like a rocking horse, with a plastic head that rolls out on a wheel, and you rope it. If you miss, gravity brings it back. It even has legs in case you want to throw a heel loop.”

Wallum even built a stagecoach. He had sold paintings to Marriott Hotels, so he asked them to sponsor his stage in the South Dakota Centennial Wagon Train in 1989. Even though they had no hotels in the state, they finally agreed to back him for the summer, and then they bought the coach. He also drove a cavalry wagon for the film “Dances with Wolves,” and raced a wagon in “Far and Away,” a movie about the 1892 land run in Oklahoma.

The constant need to market his work keeps Wallum on the road more than he’d like, sometimes to shows and sometimes to peddle his work to specific clients. His paintings are mostly 24x36-inch scenes of roundups and branding and ranch chores in rain and snow and every kind of weather, every task in cowboy life, plus the loafing that sometimes follows a job. And always horses. Framed, Wallum’s canvases start at $1,500. “You have to take the paintings where the money is,” he said.

Wallum’s marketing strategy, learned early in his career in Oklahoma, is a bit unorthodox. It’s direct, and often effective. “I had arrangements to display paintings in a couple of steakhouses where I knew the big oil men came late in the evening,” he said. “I’d come in on Friday and Saturday nights and switch paintings while they were there. It was a good trick. Otherwise they probably wouldn’t have paid much attention to my work.”

“The other trick I’ve learned is that if anybody ever opens their mouth and wants to buy a painting I move in with them,” he chuckled. “They have to buy one to move me on down the road. But actually I have a lot of repeat customers, and that’s always nice.”

|

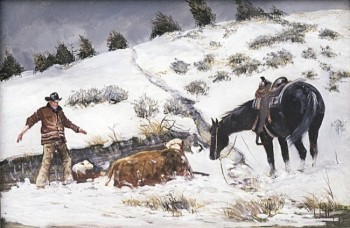

| The constants in Galen Wallum's paintings are cowboys and horses. |

None of his work has been reproduced; every painting is one of a kind. But now that he feels better established, he’s considering selling prints of a few of his best.

“I figure I’ve done close to 2,000 paintings in 41 years,” Wallum said. “I used to really crank them out, sometimes three or four a night. They were awful weak back then. I found that it’s better to take your time.” Wallum produces about 30 oil paintings a year. Even at that pace, along with marketing, he’s a busy man.

“Lock me in a room and I can paint,” he said, but it works best if I have references, models or good photographs.” He sketches only a basic outline before he paints, because “sketching will make your eyes burn like crazy.” He usually has two paintings going at once, which he calls “sister paintings.” He moves from one to the other as he adjusts his colors.

Though working on commission limits his freedom more than he likes, Wallum occasionally does paint what other people conceive. “If somebody brings me something they want done I tear into it and get it done and make them happy,” he said. “An advantage is that you learn some discipline along lines you might not normally tackle.” And that’s good for an artist, he says. “If you get locked into something because it sells and just keep repeating yourself, that’s kind of risky business.”

What does the future hold for Galen Wallum? “I don’t know. I hope I can keep painting ‘til my last days,” he said. “That way I won’t have to get a job. I’ve always avoided that.”

Wallum says he can paint cowboy life because he’s lived it. He knows if a painting feels right. “I try not to romanticize this life. I’ve seen a lot of old cowboys all banged up, and I knew I wanted to quit cowboying before I got like that. But I’ve been there. I can paint a picture of an old man pulling a calf on a snowy day and I can do it pretty accurate.”

Galen Wallum knows that his particular realism will one day be nostalgia, as the life he memorializes fades into the sunset. “And it’s coming on fast,” he says. But right now, on the plains and in the Badlands of South Dakota, the last of the old cowboys still live — in the saddle, and on Galen Wallum’s canvas.

Comments

As we say in the Navy, Bravo Zulu Galen!

I felt like I had made the buy of the century!!

Joy Wallum ran errands

for the great artist, Harvey

Dunn!! Galan Wallum is a well known artist! He called me and I invited him to come over and meet my daughter and son—in—law. He stayed for a week and we all had

a fun time. Everyplace we went, I introduced him and told them what a great artist he was. He had a few paintings with him and he left without

any! Wall Drug Store

sold a lot of his paintings.

I bought 2 and sent one to Joy and his wife, Dolly.