The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Homestake’s Pit Ponies

|

| "Old Smoky was hitched to a train of carts, each loaded with gold-laden ore headed to a Homestake elevator 400 feet underground in 1908. |

Homestake Gold Mine depended on manpower in its early years, but in 1889 seven horses and 15 snorting mules were sent down its candlelit shafts.

Sometimes referred to as “pit ponies,” Homestake’s horses were lowered into the mine as fillies. The remuda eventually reached about 90 head. Once inside, most of the horses never again saw the light of day, although a few were trundled topside during fires, miners’ strikes and for rare promotional purposes.

Lifting or lowering the horrified horses to or from workstations thousands of feet underground was difficult. The elevator’s small size as well as the horses’ flighty dispositions were not conducive to noisy, rocky rides, so they were bound head to hoof in wide leather strappings. Their eyes were covered to help calm them. The 3-inch-wide harness held them in what resembled a sitting position, like an apple hanging in a stocking. This package of nearly a ton of horseflesh was fastened to the underside of a vertical shaft elevator. The signal was given and away they went, headfirst and squirming. The practice was considered the most humane because there was no pulling force bound to the horse’s neck or head.

Homestake wasn’t alone in its need for underground horsepower, although only a few of the more than 300 other mines in the Black Hills used horses underground. Those four-legged and faithful power sources at Homestake spent their lives in darkness, plodding through dank tunnels, using steel rails and memory as their guides to the ore dumping stations. On 10-hour shifts, they pulled rattling trains comprised of as many as eight, single-hitch, four-wheeled ore carts, each loaded with about a ton of gold-bearing rock.

Every miner was issued three candles to light their way during the long shift; the horses also depended on those tiny flickering flames. Hay, oats and water for the horses was lowered to roughly built wooden stables sited at key points along each mining level. Veterinarians, harness makers and blacksmiths were always nearby if needed. Walking on rough, sharp mine debris meant the horses required regular shoeing.

Not all Homestake horses were destined to a lifelong assignment underground. In the 20-year horse era at Homestake, some lucky ones were rewarded with visits to the surface and temporarily blinding daylight. During an 1893 mine fire, horses working in that area of the mine were brought above ground until the fire was doused.

A miner’s strike in 1906 posed a problem for mine bosses because the strike did not allow union workers to enter the mine, though the animals had to be fed and watered. Until the walkout was settled, all the nearly 90 horses were brought to the surface for an unscheduled vacation. It is said that the horses, once out of the mine, had to be taught how to eat green grass again.

|

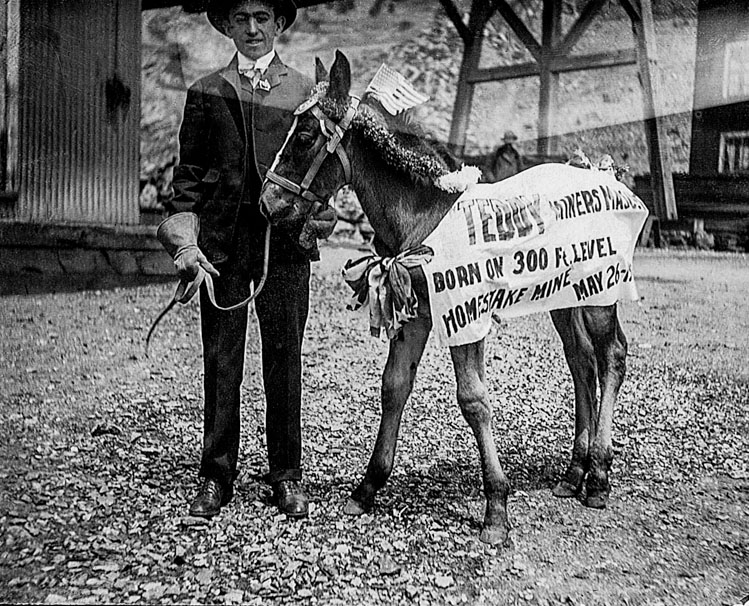

| Homestake Mine mascot "Teddy" was born 300 feet underground on May 26, 1902. The colt was named after Theodore Roosevelt, then in his second year as president. |

A surprising turn of events occurred in the early morning hours of May 26, 1902 when a colt was foaled at the 300-foot level. Underground births were not expected since all the horses below ground were mares. Apparently one mare had been impregnated before she was lowered to Level Three.

Homestake officials took advantage of the opportunity to impress then President Theodore Roosevelt as well as the thousands expected to attend Lead’s 1902 Fourth of July celebration. The two-month-old foal was brought to the surface. Named Teddy in honor of the president, it became the hit of the holiday. Teddy was never assigned underground work.

To help the City of Lead stage its 1903 Labor Day celebration, a veteran mare named Mollie that had worked in the mine for 14 years was selected to make the trip to the top and be featured in a Homestake Mine display. Her eventual work assignment was not disclosed, but it is doubtful that she was returned to her former purgatory. She probably joined the surface herd, re-learned how to eat grass and enjoyed the rest of her life working daylight hours.

Soon after Mollie’s hoist to sunlight, the last of the horses working underground also made the upward journey. By that time, improved underground transport systems rendered real horsepower obsolete in pit mining. Steam engines were the first mechanized replacement, followed by compressed air, battery and electrical inventions. With each improvement, fewer pit ponies were needed. Gradually, horses were retired and hauled to the surface. The phaseout began in 1908, though horses played a role in the mine’s surface work well into the 1950s.

The mine closed in 2002. Now in its depths is the Sanford Underground Research Facility, where scientists search for neutrinos and dark matter — particles so tiny, mysterious and elusive that brainpower is in higher demand than horsepower.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2022 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments