The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

A Farmer’s Story

|

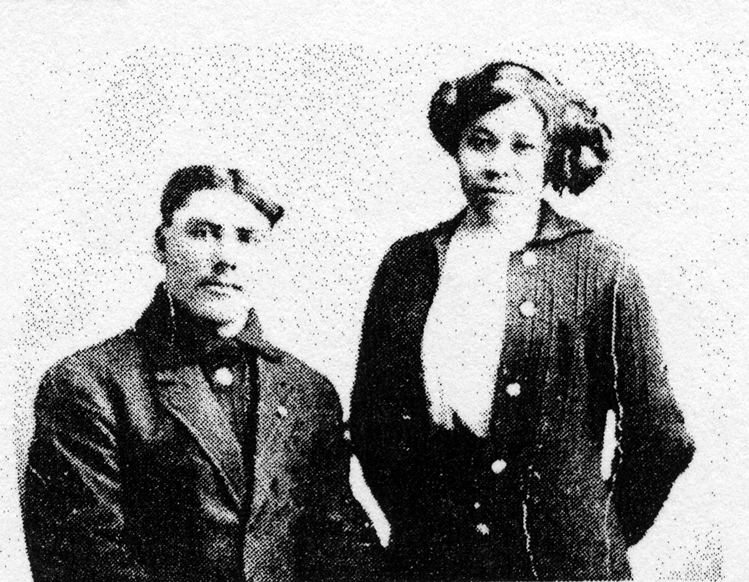

| Johnny Cloud, a colorful Sisseton farmer, has many descendants in Roberts County. They include his daughter, Marlene (left) and a grandson, James Cloud. |

When South Dakota Magazine began publication in 1985, we hurried to interview some of South Dakota’s elder statesmen because we wanted to collect their stories firsthand. Ben Reifel and Sigurd Anderson were two such leaders. Reifel was born in a log cabin on the Rosebud Reservation in 1906 and became the first (and only) Native American to win statewide office in South Dakota.

Anderson was born in Norway in 1904, and served as governor in the early 1950s. Although Anderson and Reifel were Republican office-holders of the same age and era, they told very different stories. There was one exception: both mentioned an Indian boy from Roberts County who wanted to be a farmer.

They each spoke of him when we asked about race relations in South Dakota. Neither seemed to know any details about the boy, and the story was almost too cute to be true — like the feel-good anecdotes that politicians like to tell. We figured that one of the old pols had heard it from the other, so we gave it just a few paragraphs in Reifel’s feature article in 1989. However, I did repeat it on occasion when I was asked to speak at various events.

Anderson and Reifel told the story like this: the boy grew up on the reservation speaking only the Dakota language and a little German. His teachers told him he must learn English if he wanted to be a farmer. “After all,” said one teacher, “you don’t know how to farm, so you’re going to have to ask.”

That made sense to Johnny. He worked hard at English and other subjects. Years later, he was able to rent a patch of land in Roberts County. He decided his next step would be to meet the neighbors, who gathered for coffee every morning at the local grain elevator.

In farming country, a grain elevator is like the country club to an advertising executive or insurance agent. That’s where a farmer goes to “network” with his associates. The young Indian boy didn’t know the meaning of networking, but he intuitively understood the concept. So he bravely walked into the grain elevator and sat down at the table, ready to learn.

Imagine his surprise when he found that — after years of learning to speak English — the farmers were not speaking English, but some other language. He wasn’t sure what tongue it was, but it wasn’t German or English or Dakota. He wondered if his new neighbors were intentionally snubbing him. He didn’t know what to do. So he went home.

A few days later, Johnny mustered up the courage to confide in his nearest neighbor. He went to the man’s farm and blurted out his confusing experience at the grain elevator. “I spent years learning to speak English so I could be a farmer, and when I went to meet the other farmers they were talking something else,” he said.

The neighbor explained that nearly everyone in the community spoke Norwegian. He said the farmers at the elevator certainly didn’t mean to slight him. “They just weren’t thinking,” he assured the young man.

The two came up with a plan. The young Indian already knew three languages. Surely he could learn a fourth. A few weeks later, Johnny and his new friend returned to the grain elevator. They sat down at the table and Johnny, the Dakota Indian, introduced himself in Norwegian. Imagine the looks of surprise on his new neighbors.

Speaking in Norwegian, Johnny clumsily explained that he always had wanted to be a farmer. That his teachers told him to learn English so he could talk to his neighbors. That he still wanted to be a farmer, and he knew he needed their help and advice. And that he would help them whenever he could.

Before he could speak any further, because his Norwegian was so torturous to hear, they all welcomed him with handshakes and offers to help — offers spoken in plain English. And Ben Reifel said that was the last time anyone spoke Norwegian at the grain elevator, because they realized they had been excluding their non-Norwegian neighbors. Anderson and Reifel said the Indian boy became a skilled farmer and community leader, and all lived happily ever after.

That was their story. Whenever I told it in public, I admitted that I didn’t know the Indian boy’s name or the community where it happened. And, of course, I wasn’t even sure it was completely true.

A year ago I was asked to speak at the Center for Western Studies’ annual Dakota Conference in Sioux Falls. Wanting a feel-good conclusion to my talk, I told the story of the Indian boy from Roberts County. As I spoke, I could see that Wayne Knutson was paying close attention. He is the retired Dean of Fine Arts at the University of South Dakota and a patriarch of the arts across South Dakota.

As soon as I finished speaking, Knutson hurried to the front of the room and said to me, “That’s Johnny Cloud! I knew him. He was a big, tall Indian farmer from Sisseton who always greeted us with a god dag!” Wayne, it turns out, was born and raised in Roberts County. He said Johnny Cloud was one of the most memorable characters from his childhood in the 1940s. “Most of the Native Americans seemed more reserved, at least when they were downtown, but Johnny was a gregarious man with a hearty laugh that drew me to him,” Knutson said. “And he loved to show off that he could speak Norwegian. We’d heard that he had learned the language so he could do business with the Norwegian families,” he said.

Knutson remembered Johnny Cloud delivering “little Norwegian speeches” to the clerks in Stavig’s Department Store on Main Street. “Then he would laugh his big laugh, because it tickled him so much. I can still hear his laughter ringing out.”

I could hardly believe my ears, as Knutson brought Johnny Cloud back to life. My estimations of Anderson and Reifel — though already immense — grew still higher. Why had I doubted that the story was true?

As soon as I returned to the magazine office in Yankton, I looked in the Sisseton phone book for the Cloud name. I found James Cloud and dialed his number; James promptly answered. I asked if he knew Johnny Cloud, and he said both his father and grandfather were named John.

When I told him my story, he said his grandfather was the tall, successful farmer who spoke Norwegian. “I’m looking out my window at the land he farmed,” James said. He invited me to stop by on my next trip to Roberts County.

Sisseton, a tidy little city of 2,600 people, sits on flatlands just below the Coteau Hills. Sometimes in the winter, the sun is shining in Sisseton while a fierce blizzard rages in the hills west of town. Atop the Coteau, three markers have been erected to memorialize three separate incidents involving travelers lost in such storms.

The Sisseton area has a lot of variety for its size. The Lundstrum family’s religious ministry is headquartered there, as is the Schiltz family’s goose farm and factory, which processes 100,000 geese a year.

A glacier slid across this land a mere 20,000 years ago, creating dozens of pretty little lakes that are now ringed by cabins and resorts. The Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Sioux Tribe runs a bingo hall and a community college just south of Sisseton. The tribe has a rich history. Its people, starving and denied supplies in Minnesota, battled the Minnesota militia in 1862. When the hostilities ended, 38 Indian warriors were hung on Christmas Day. It is called the largest mass execution in America’s history. Chief Gabriel Renville led the tribe into the 20th century, and many of his descendants live in Roberts County today.

|

| Johnny Cloud and Bessie Derby were married at Sisseton in 1912. |

Northwest of town is the West’s smallest and prettiest forest, a 900-acre state park known as Sica Hollow. Hikers, horse enthusiasts, photographers and bird-watchers frequent the place, and sightseers come in the autumn to marvel at the hardwood trees’ golden foliage. Who could blame Johnny Cloud or any young man for wanting to make a living here on the land?

Driving into Sisseton on a weekday morning, I wondered if anyone other than James would remember Johnny Cloud. It was too early to call on James, so I stopped at the Cottage Restaurant on Highway 10 for coffee and eggs. Ken Erdahl, a longtime Sisseton banker, was seated in the next booth. We struck up a conversation, so I asked him if he knew Johnny Cloud.

“He was a big, tall guy,” answered the banker. “He was kind of husky. He was a good customer of ours, and a good farmer. When he wasn’t farming, he liked to hunt on Buffalo Lake. He liked to be called Goose Hunter.”

Erdahl recalled that Johnny spoke Norwegian, but he hadn’t heard the story of why he learned the language. He wasn’t surprised that Anderson and Reifel might have known the Indian farmer. “Johnny was well respected around here and very sociable,” said the banker. “He hung around Mel’s Diner for coffee. He was a very nice fellow.”

Erdahl was working at the Roberts County National Bank when Johnny borrowed $1,400 to buy his first new tractor, a shiny red “M” Farmall. “He sold it 20 years later for $1,500 and he was very proud of that,” said the banker.

Everywhere we went in Sisseton, old-timers remembered Johnny Cloud. They didn’t know of his encounter with the neighbors at the grain elevator, but their memories of his good nature, his intelligence and his passion for farming all supported the Anderson/Reifel story.

At the Roberts County National Bank, the Torness family paged through their local history books and found some specific information on John Melvin Cloud. He was born on the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana in 1891 and came to the Sisseton area as a teenager to live with relatives. His ancestry, like many Indians in Roberts County, traces to Chief Renville. Johnny married Bessie Derby in 1912 and they began a small farm on land just north of Sisseton.

Late in the morning, I drove north of town to the old Cloud farm. James, a short and slender man with jet-black hair, said he was young when his grandfather died in 1968. “I do remember helping him to feed the chickens, and if you didn’t do it right he would get after you,” he laughed.

“Come in the house,” he said. “My mother knew him.” There in the living room, lying in a hospital bed, was James’ mother, Goldie. She was injured in a car accident in 1974, and has been confined to bed ever since. She was already the mother of 10 young children when the accident happened. Today, nine of the 10 still live in the Sisseton area and James says they all help care for mom, but he is there constantly, attending to her needs.

Goldie, despite her paralysis, is a happy and content woman. Her living room is filled with pictures of grandchildren, and she looks out a big picture window at the fields that her father-in-law once farmed. She remembers him as a big, friendly fellow who loved his neighbors and his family.

She married his only son, John Jr., in 1947. Goldie’s nearest neighbor is Marlene Campbell, her sister-in-law and Johnny’s daughter. Marlene lives less than a quarter-mile down a gravel road. We knocked on her door, and she was happy to answer our questions as well; but she noted that her husband had died two years earlier, and the shock affected her memory. Still, she had good recollections of her father. “A lot of the farmers would come to him because he could speak German and Dakota,” she said. “He probably learned it in Montana before he moved back here. He was always happy to translate for people.

“He helped people out, and he loaned machinery to the neighbors,” Marlene said. “He also would go to the jail and take the prisoners for a day or two. They were always so glad to get outside and work in the fresh air.”

None of the Cloud family remembered a specific story of Johnny learning Norwegian to speak at the grain elevator. But they agreed that it sounded a lot like him, and they confirmed his passion for farming. Marlene says her father built a barn even before he built a house. “He loved his farm and he was very successful,” she says. The big red barn was recently torn down, but a grove of trees and his old granary still stand on the Cloud farm.

“He encouraged all of his children to go to school,” said Marlene, “but I was the only one who went to the university.” She earned a master’s degree in education, and taught at Sisseton High School and the Sisseton-Wahpeton Tribal College.

Cloud family members have worked in education, health care, religious ministries and other professions. Because a boy wanted to farm — and possibly because a neighbor helped him learn a little Norwegian — his family took root in Roberts County. The benefits to the area continue to multiply, as does the Cloud family; as we visited with Marlene, her granddaughter came by the house with the family’s newest member, a three-month old baby called Azriel who has the bloodlines of a great chief and a fun-loving farmer.

While driving away from the Cloud farm, we thought that Azriel deserves the opportunity to know about her Norwegian-speaking great-grandfather. He overcame the gulfs of not just two, but three cultures — and he did it with laughter and good cheer. So, with apologies and appreciation to Ben Reifel and Sig Anderson, we’ll continue to tell the story of the Indian boy who wanted to farm.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2008 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thanks so much for sharing this story as I never knew John spoke four languages. When I was a kid (70 years ago) my dad and I would fish in the river on the John and Bessie Cloud farm. They would always welcome us into their home. Yes, John was a big man with a big heart.

This is a story of a man who obviously had a great influence on many people. Thank you for sharing this.

And the last time I saw Marlene, Fr. Campbell's widow, was at Tekakwitha Senior Center where she was living. We had gone to see Francis Crawford, another successful Dakota farmer, who lived to be 105. I went over to Marlene and said, "You are the lady in your mother Bessie's picture of three beautiful daughters--- with long dresses and carrying large brim hats---who were in Minneapolis posing in front of a backdrop of Minnehaha Falls to have their picture taken." Then I hugged her and said goodbye. As I left, I heard her explaining to the woman at the desk that I was talking about her and her sisters.

The First National Bank of White Rock was purchased July 27, 1918 by John L. Caldwell and his son-in-law, A.W. Powell. A.W. Powell was not related to the previous owners.

Of the 21 banks existing in Roberts County in 1933, The First National Bank of White Rock was the only bank allowed to remain open after the Bank Holiday was declared in March 1933. Following the closure of all four banks in the county seat of Sisseton, the Comptroller of the Currency authorized the transfer of the charter to Sisseton and the change of the bank’s name to The Roberts County National Bank of Sisseton on August 12, 1933. The bank’s assets were transported from White Rock by employee F.H. Kouba. Traveling to Sisseton in a Ford Model A Coupe, Kouba was escorted by the White Rock town marshal and his shotgun.

The Roberts County National Bank began operating at 411 First Avenue East (now Veterans Avenue) in Sisseton in a building previously occupied by a bank that had gone out of business. It survived without reorganization during the years of the Great Depression. The bank moved to its current location at 5 East Maple Street in Sisseton in 1960 and continues to operate there today.

In 1956, A.W. Powell sold the controlling interest in the Roberts County National Bank to his son-in-law, Harold L. Torness, who served as bank president from 1970 until his death in 1999 at the age of 80. Torness’ son-in-law, John S. Rasmussen, and his son, William H. Torness, serve as the bank’s C.E.O. and President respectively. The Roberts County National Bank of Sisseton continues to be the only independently-owned hometown bank in Sisseton and is proud to have served the community for over 100 years.

Both Fr. Ron and Marlene have passed, and I miss them immensely.