The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

King Ziegler's Car Farm

|

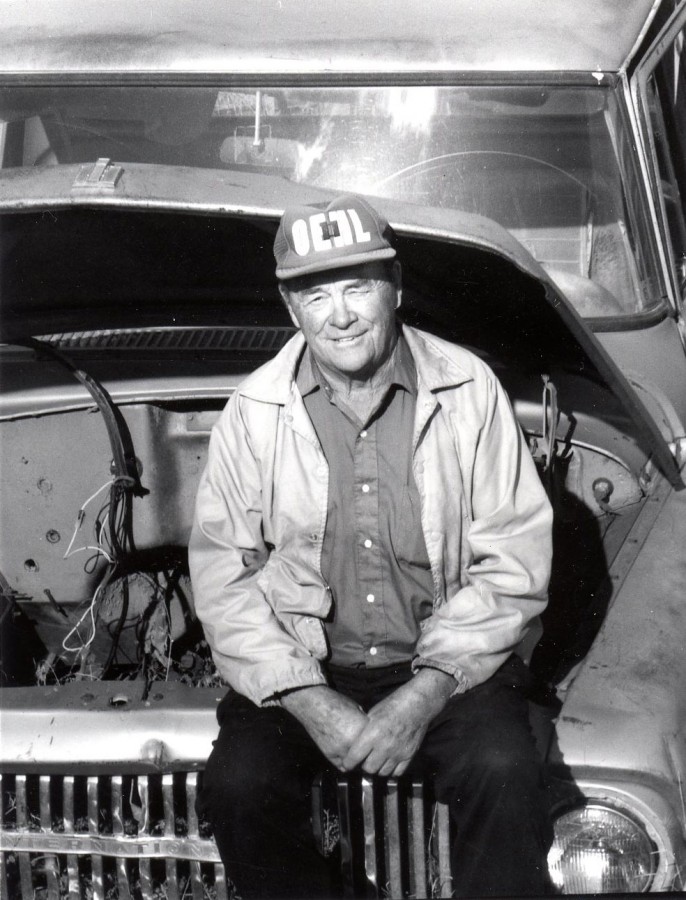

| People came from miles around to search for treasures in Alfred Ziegler's salvage yard near Scotland, South Dakota. |

Auto junkyards were once a staple for a town. The carcasses of cars and trucks were kept in rows on the outskirts of town, where one or two grease monkeys made a decent living by selling parts.

Today’s salvage yards have more in common with K-mart than with the junkyards of yesterday. Vehicles are stripped of radios, rims, alternators and everything else of value. The parts are checked, cleaned, inventoried and available to buyers across the USA thanks to the Internet.

It’s a very efficient system of recycling, but something is missing from the business model practiced by King Ziegler, who ran a junkyard near Scotland in the 1990s. When South Dakota Magazine visited him in 1996, King was earning a living from a crop of rusted iron and nostalgia. People came from miles around –– some from as far away as Europe and Asia –– to search for treasure in his 30-acre field of cars.

His real name was Alfred. But if you asked for Alfred Ziegler at a cafe in his Bon Homme County town the locals would look puzzled until you added that he is the guy with all the old cars.

“Oh, you mean King,” everyone would say in unison. “King Ziegler.”

King ran a place some people would call an auto junkyard. In the phone book, it was called King Ziegler Salvage. So you’d expect to arrive and find workers removing parts from car carcasses. Grease. Oil. Sweat. Noise.

None of the above. Blackbirds sang in a nearby cornfield. A herd of sheep grazed between rusting automobiles. A rooster crowed on a nearby farm and a donkey brayed in reply. That’s about as noisy as it got at King Ziegler Salvage.

“When he went into business, everybody thought ‘How do you make any money on this junk?’” said Wilbur Foss who ran a hardware store in Scotland for 17 years. “He’s one of a kind. He built a reputation far and wide. Everybody likes him and he likes everybody.”

If that’s true, it’s not because he was so accommodating. King didn’t remove parts from the cars. That was understandable when we met him in 1996 because he was 79 years of age. But he never did believe in removing parts before they were needed. “I have the customer take the parts off. I tell them if they take if off, they’ll know how to put it on,” he told us.

That might seem quaint to big-city salvage yards with rows and rows of Chevy transmissions, shelves full of GM radios and boxes of Ford alternators.

Real steel builds lasting memories. And the proof is at King Ziegler’s car farm.

King’s self-serve salvage wasn’t tailored to the customer in a hurry. He didn’t have an inventory of the cars in his field. They were not inventoried on a computer. They were not even logged on a yellow pad. And he didn’t pretend to remember what’s available. “Just go take a look,” he advised. Customers seemed to like that attitude. It would never work for Wal-mart –– but King Ziegler Salvage was as different from chain store retailing as a whale is different from an ocean liner.

A business school grad might think the Scotland salvage yard needed more modern management. But after spending an afternoon at King’s field, you’d start to wonder if maybe the rest of the world has gone overboard on organization.

After all, his system worked splendidly. He spent nothing on advertising, yet customers came from all over the world. He had only an eighth grade education, yet he made a good living without getting any grease in his fingernails.

He had no labor costs. No labor worries. No stress. No office expenses. No signs. The 1950 Chevrolet wrecker he used to hoist or haul cars had a phone number painted on the side. But it was not his phone number.

He spent nothing on mowing. Instead, he invited a good friend, Elmer Brandt, to bring a herd of sheep to the field every summer. “I guess I could run sheep myself but then I’d have to put up hay to feed them in the winter,” he said.

He closed when the weather was bad. He closed for much of the winter. Customers could call him in an emergency. But it’s hard to imagine why there would be a critical need for a 1949 Studebaker carburetor.

King Ziegler didn’t start out in the car business. He was raised on a farm near Tripp, where he had a stud horse called King (that’s where his buddies found his nickname). After service in World War II, he was in the oil business at Kaylor. “I bought cars to fix them up and all of a sudden I got into this business,” he remembered with a wry grin in 1996.

He didn’t have time to repair all the fixer-uppers he was buying so he started to park them in the field at his farm near Scotland. He bought most of the cars for $25 to $100. Sometimes, dealers sold him used cars they couldn’t move. He also attended farm auctions. And he bought many privately. “People even tried to give me cars but I always paid something. I wanted to be fair.”

At first, he put the cars in neat rows. But as the field began to fill, he squeezed the last few hundred in wherever they would fit. An open path meandered between the cars but it got narrow at some points –– barely wide enough to squeeze King’s two-passenger three-wheeler motorcycle through.

King continued to operate his Kaylor company until 1972, when he sold it and moved to Scotland to run the salvage yard full time. He quit buying cars years in the 1970s, when the lot filled up. He estimated there were about 1,500 cars and pickup trucks in the field, as well as dozens of old tractors, grain threshers and other farm equipment. King Ziegler was one of the last people on earth who could still sell a manifold for a Cockshutt tractor.

Most of his collection dated back to the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Twenty years ago, there were lots of salvage yards with cars of similar vintage. But when iron prices increased and machines became available to crush cars, many dealers “recycled” their older models.

For sentimental reasons –– and because it seemed like a waste of good parts –– King never sold to the scrap dealers. “I just didn’t care to crush my cars. I thought they might be useful to somebody someday.”

It was a good business instinct. “I had people here from Sweden last week looking for Pontiac and Buick parts,” he told South Dakota Magazine. “We had somebody here today from California.” They came from all parts of Europe and Asia as well.

Most customers had so much fun looking around the field that King joked about charging admission. But he never would have done so. He made his money from the parts they hauled away. A man with an armful of chrome from an old Pontiac wrote a check for $35. “I’m not trying to get rich on anybody,” King said. “At least I’ve got something to do and I get to visit with a lot of people.”

Most of his visitors were professional car restorers. Others had an old car or two at home. “Most are fixing up a car like the first one they ever owned in their youth.”

King’s collection was especially well-stocked with Pontiac and Buick parts. That’s because Bon Homme County residents loyally supported the late Frank Pillar, who sold those name brands for decades at his lot in Scotland.

“Frank was one of the top-selling small town dealers in the United States,” said Wilbur Foss. “People in these parts were very loyal to him and he was loyal to them. He took care of their car problems, even if it had to come out of his own pocket.”

Frank’s brother, Ed, ran a Ford dealership in Scotland and many of his vehicles are also in the lot. Pillar decals can still be found on many vehicles.

Some insightful people, realizing King had a good thing going, have offered to buy the place. But how do you put a price on a business that markets rusted iron, chrome and nostalgia?

Besides, if an appraiser did a true inventory, Ziegler’s collection would have cost more money than most buyers would have available. “Some people tell me there’s a million dollars worth of cars out here,” says King. “I don’t think so.”

King lived modestly for a paper millionaire. A lifelong bachelor, he rented an apartment above Scotland’s main street and ate most of his meals at a local café.

He drove a 1980 Ford pickup. He also owned a fully-restored 1959 Ford convertible that he drove in local parades.

His business headquarters was a small, wooden building at the entrance of the field of cars. Inside, a girl-in-a-bikini calendar from an auto parts store stood out as the most colorful decoration. The office was full of reading material that he enjoyed between customers.

Like many entrepreneurs, King Ziegler was the first to admit that he sort of stumbled into success. Who would have dreamed that the cars he collected would be such prizes in the 1990s?

Which brings one to wonder whether today’s Tauruses, Intrepids and Escorts will be as popular in 50 years as the Studebakers, Mercuries and ‘57 Chevies of yesterday? Should someone be saving today’s discards?

King had his doubts. “They make pretty light stuff these days,” he said. “They’re like a pop can. With all the salt on the roads I don’t know how long they’ll last. Years ago these cars weren’t exposed to all that salt. That’s why Minnesotans are always coming up here to buy parts. They used more salt.”

Besides that, he said, today’s cars have so many plastic and fiberglass parts that they aren’t likely to hold up long enough to become collectors’ items. People don’t tend to have fond memories of cars that are cracking and falling apart, he said.

Real steel builds lasting memories. And the proof is at King Ziegler’s car farm.

EDITOR'S NOTE – This story is revised from the Nov/Dec 1996 issue of South Dakota Magazine. King Ziegler died a few years later. To order this back issue or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments

And they would say if we looked closely there would be spots of blood spattered

A broken windshield from a head on collision. We would take the bait hook, line, and sinker. I think back on those days and maybe hearing and seeing those cars maybe changed our outook on our driving our own cars. Maybe King had all along was showing and at the same time teaching us a lesson. I am glad to hear how they went from stacked up vehicles to a computer system telling you are in luck because they have the part you have needed for so long is there. I really think that King did actually teach us something, he knows hands on is the best way of remembering, so if you took it apart you should be able to put the piece back on. I am so glad I ran across this article, my hometown of Scotland. God's Blessings to all who are trying to keep the city alive.