The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Life in the Gap

|

| The namesake gap in the hills can be found by taking Highway 101 (aka the 7-11 Road) northwest of Buffalo Gap about 2 miles. The opening begins where the road intersects Beaver Creek, just west of Highway 79. |

KAY STREETER HAS inherited Buffalo Gap history — everything from land, cattle and buildings to scraps of paper. It couldn’t be in better hands.

“I was born on the plains,” she says. “I’m a child of the land and there is something about it that has a deep call for you.”

Streeter grew up in southeast South Dakota and arrived in Buffalo Gap — in the state’s southwest corner — as a young bride, marrying into a family steeped in ranching, banking, public service and saddle-making.

She eventually moved away to teach at Montana State University in Billings but returned to Buffalo Gap in 2010 to care for elderly relatives. She’s happy to be back in the town of 100. Her oldest son oversees the family cattle operation because Streeter is busy with other priorities, including the family residence that was built by homesteaders and eventually rolled into town with horses and logs a century ago. Streeters have owned it since 1947.

She also hopes to repair an old barn moved to town by N.B. Streeter in the early 1900s to house his team of horses when he commuted from the ranch. She and a friend, Kathy Sanford, bought another historic home, “because we were worried what might become of it,” but much to her four adult children’s delight, they found a satisfactory buyer who is doing the restoration.

|

| Darla Sanson Semmler (left) and Kay Streeter (right) welcome a visitor at the Buffalo Gap Post Office. |

Now she is delving through her mother-in-law’s papers. “Eva Streeter was the Buffalo Gap postmaster, and she ran a women’s hair shop from the house,” she says. “She kept a journal and wrote down why the ladies were getting their hair done — maybe for a wedding or because someone was visiting. If they got a permanent, she served them lunch.”

Her chief partner in Buffalo Gap history is Darla Sanson Semmler, a longtime friend who ranches near town. “The Streeters and Sansons have lived together up on Red Valley Road, on the south side of the park fence, forever,” Streeter says. “They did everything together. Back in the 1930s when people didn’t have much money the government bought the land for the park, except for the Streeters and Sansons who wouldn’t leave.”

That park is Wind Cave National Park, a wild prairie and forest ecosystem that sits atop one of the world’s longest caves. Nearby is Custer State Park, and east of town is Buffalo Gap National Grasslands, the second largest of 20 national grasslands in the United States, encompassing 600,000 acres in scattered tracts that run from the Badlands near Wall to the southwestern tip of South Dakota.

“When the government started buying out the ranchers for the Wind Cave park, they told the people that they could have anything they could salvage off the land,” Streeter says, “so they took fencing, posts and even entire houses. They thought nothing back then of just putting a house on a set of logs and rolling it, usually with horses, for miles.”

*****

BUFFALO GAP’S STREETS and the rural roads around it are graveled with the sand that rims the Black Hills in a formation nicknamed the Red Racetrack. The gravel is passable on a sunny day, but rain or snow makes it a slippery muck. Still, visitors show up to explore.

“One fellow was out here looking for a town called Mohlerville on his GPS,” says Darla’s husband, Merle Semmler. “I told him, ‘You’re here!’”

Mohlerville was a very rural post office, but it has disappeared into the ocean of grass, interrupted only by the remaining ranch buildings, fences, cattle herds and perhaps an occasional field of grain.

“Hay and grass,” Darla says. “That’s what we do. We are on the Angostura Irrigation District, so we have at least three, maybe four cuttings of hay. One farmer grew sunflowers for a couple of years, and another tried soybeans, but they didn’t do worth a dang. There was more corn a few years back than there is now.”

Any sheep? “Don’t even ask!” laughed Darla.

“If they have sheep, it might be one or two for the kids’ 4-H projects, or maybe a few goats,” added Merle.

We’d already committed the Old West faux pas of inquiring about sheep at Rancher Feed & Seed and got a similar reaction. This is cattle country, populated by cows and calves, and the horses, dogs and people who tend to them. The range war between sheep growers and cattle ranchers is over, and the latter have prevailed around Buffalo Gap.

*****

THE TOWN OF BUFFALO GAP came to life in 1876 when miners and traders flocked to the Black Hills. Streeter says the town took its name, “from a break in the Black Hills that provided a reasonably wide valley exit for Beaver Creek.” Buffalo traversed the gap for centuries as they made their way from the Black Hills to the Plains. Stagecoach drivers followed the buffalo trails when gold was discovered in the Black Hills. So did cattle herds, cowboys and miners.

|

| Marge McColley (left) and Carrie Zoellick are volunteers at the town's food pantry. McColley, 94, grew up near Buffalo Gap and remembers when the bank was still operating in the 1910 sandstone building that now houses the pantry and serves as city hall. |

The original town was built on Beaver Creek, about 3 miles east of the gap. In the 1870s, the town had four blacksmith shops, 23 saloons, 17 hotels and restaurants, two “sporting houses,” four Chinese laundries, a few stores and some tents where church services were conducted. The town boomed to 3,000 when a railroad track was laid from Chadron, Nebraska, and Buffalo Gap enjoyed the status of being at the end of the line.

However, the boom faded when tracks were extended to Rapid City and Belle Fourche. Two major fires also caused setbacks. Most of the surviving architecture, including wood frame buildings and a few of sandstone, were built in the early 20th century.

The town’s red stone bank building, constructed in 1910, now serves as city hall and as a collection point for a food pantry, which is run in part by Marge McColley and Carrie Zoellick.

McColley, 94, now lives at Custer but she grew up near Buffalo Gap and remembers when the bank stored cash rather than cans of vegetables and fruit. Zoellick came just four years ago, then lost her husband and became the town’s handywoman. She drives the city snowplow, reads the water meters, serves as secretary to the rodeo association, mows the grass, paints buildings and tends bar.

Zoellick also volunteered to be our tour guide. She showed us the new rodeo grounds on the east edge of Buffalo Gap; the Baker family donated the land and others volunteered time and materials. She also showed us the present-day Buffalo Gap Cemetery, which is about a mile from an all-but-forgotten “boot hill” where a few horse thieves are buried.

*****

DOWNTOWN BUFFALO GAP is busier than you’d expect of a seemingly forgotten town that lacks even a hard surface road to connect it to the outside world. The old-style farm store with its wooden grain elevator is still operating; so is the quaint and charming post office and two drinking establishments.

The town has a lively social life, with rodeos and horse events at the new rodeo grounds, a summer bluegrass fest and a July event called the Buffalo Gap Blowout. On Thanksgiving Day, ranch families and city residents are welcome at a community potluck in the old auditorium.

Buffalo Gap boasted 23 saloons at its peak population. Today there are two.

|

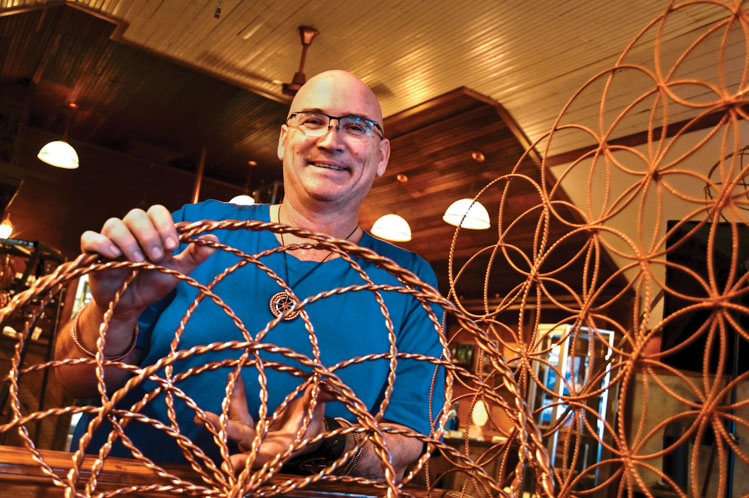

| Buffalo Gap's biggest enterprise is TwistedSage, a business dedicated to the healing properties of copper. Brian Besco (above), the founder, and a team of family and friends manufacture and market myriad products and ship them around the world from the town's tiny post office. |

The Last Chance, run by retired postmistress Shirley Carlson in yet another red stone building, was constructed in 1907 as a hotel. Carlson’s business partner, Tom Huninghake, has restored it and several other structures. She opens Last Chance every day of the year, mostly serving the ranchers who surround Buffalo Gap. An elk’s head with massive antlers hangs above the bar, near a cautionary sign — NEXT BEER STOP GOING EAST, 114 MILES; that would be in the town of Interior, on the other side of the national grasslands, the Pine Ridge Reservation and Badlands National Park.

Across the street, Elray Rosaaen operates the Water Hole. Rosaaen came to Buffalo Gap 15 years ago when he found an affordable trailer house. He built a bar, as well as the attached Buffalo Gap Trading Post, a secondhand shop and convenience store with grocery staples.

Rosaaen’s inventory ranges from wildlife mounts to artwork, appliances, hides, fishing rods and hundreds of pairs of cowboy boots. “There’s a lot of dead cowboys around here,” he lamented.

Buffalo Gap’s biggest business is TwistedSage Studios, a company that seeks to improve the health of the cowboys — and people around the globe. Brian Besco, the founder, was raised on a ranch near town. He says his healing products blend science and spirituality. By precisely cutting and shaping copper, his staff creates products designed to heal people by enhancing their positive energies and bringing coherency to chaos.

Besco believes the products are a refinement of the ancient theory that copper can alleviate aches and pains. “This can make all our organs function better, by cleansing the emotional and physical energies,” he says. He now travels the world, sharing the TwistedSage philosophy.

He and his crew — which includes family and longtime friends — produce bracelets, pendants, tensor rings, wands and numerous other products, including a ring that attaches to cell phones. They package and ship the products daily from the small, historic post office a block away. Outside his workplace is the Giant Pyramid, a spindly tower created for last year’s Disclosure Fest in Los Angeles, a mass meditation event that featured yoga, music, arts and healing therapies.

Besco says visitors to Buffalo Gap are welcome to stand or sit under the pyramid and “just be.” He’s also developing an energy spa in an old storefront that was once headquarters for the Streeter family’s saddle shop. It will feature smaller energy chambers for visitors.

“We hardly do anything locally,” he says, “but over the past five years, people are really getting into the world of consciousness so we hope this new studio can be a place where they can come to learn and experience that and to heal. We see a lot of miracles take place every day.”

Gold brought the first boom to Buffalo Gap. Cattle has kept it going. Copper is adding a new twist.

History is still being made in the gap.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2022 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments