The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

A Lonely Place at Ideal

|

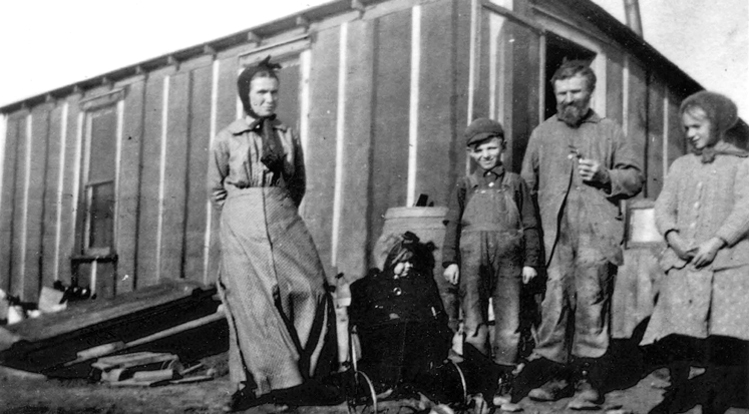

| The Koenig family (from left: Martha, Anna, Martin, Heinrich and Bertha), was photographed before abandoning their homestead for Minnesota. |

Heinrich Gustav Koenig was serving his ninth year as pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church, a rural German congregation south of Canova. His salary of $500 per year was supplemented with beef, pork, eggs, garden produce and oats from his congregants.

|

| The Koenigs fording the White River before arriving at their homestead. |

Heinrich and his family had food and shelter but he worried he couldn’t save enough to buy a home after his retirement. Then he read that homesteads would be distributed by lottery through the 1887 Dawes Act, which opened much of the Rosebud Reservation for white settlement. He traveled to Gregory in 1909 to register along with future president Harry S. Truman and thousands of others. Hoards of hungry men, excited horses, yipping dogs and a jangle of harnesses contributed to the pandemonium on the day of the drawing. Harry Truman drew a blank, but Heinrich won 160 acres in Tripp County near Ideal, and a new beginning for his family.

He resigned from the Canova parish, and he and his wife and four of their five children — son Martin and daughters Hulda, Frieda and Bertha — embarked on their great adventure in the spring of 1910. Gustav, their oldest son, remained behind as a farmhand near Canova. He would rejoin the family after the fall farm work was done.

The Koenigs loaded their livestock and the family’s possessions aboard an immigrant train that took them as far as Kennebec. After reloading their possessions onto a wagon, they struck off across the prairie to the homestead site, about 40 miles southwest. Along the way they would see nothing but prairie. Eventually, the Koenigs came to the White River, which had to be forded in order to reach the staked-out land 3 miles beyond. It was spring and most of the pasque flowers had already bloomed. Prairie chickens boomed their spring mating call and strutted on their dancing grounds.

The Koenigs built a 12-by-14-foot claim shack on a knoll overlooking their future 80-acre field. Pastor Koenig dug a root cellar adjacent to the house. The family began work so quickly they didn’t have time to determine the vagaries of soil and climate, the cycles of the seasons, and finicky violent moods of the sky.

|

| Prairie neighbors gather in a procession to carry the caskets to the grave. |

They broke the sod and planted a garden that included hollyhock seeds, Harrison Rose bushes and rhubarb roots that Martha had brought from Canova. Pastor Koenig also transplanted three ash trees on the west side of their home.

They hauled water from the White River, flowing out of the Badlands, but it was not suitable for human use. Fortunately there was a spring in a nearby ravine and rainwater was also caught and saved. After the crops were planted, Heinrich began constructing a dam 300 yards northwest of the house. A heavy rain the following summer filled the dam’s reservoir. Martha could now irrigate her yellow Harrison Rose bushes, rhubarb and hollyhocks. There was water for the rest of the garden. No longer would the family have to bathe in dirty water.

Pioneer children created their own entertainment and fun. The three oldest children constructed a raft made with lumber left over from the house and small granary. On the morning of July 24, 1911, Gustav and Frieda launched the raft. Hulda, Bertha and Martin played on the bank of the dam. It is not known how the raft capsized. Gustav and Frieda did not know how to swim. Hulda heard their screams and plunged in to save them. Tragically, all three children drowned.

|

| The gravestone provided by Koenig’s old church. |

Martin, then 8 years old, ran barefoot a mile south to tell neighbor Elof Lanz. Daughter Bertha ran southeast to alert neighbor George Leats. Soon several neighbors arrived at the Koenig homestead. The three bodies were retrieved, laid in the shade of the homestead shack and covered with blankets. The July heat was overbearing and augmented the communal grief. Mrs. L.F. Heller, a neighbor, reported that no one slept that night. A neighbor with a fast team and wagon headed for Gregory, 40 miles away, to get three caskets. Mother Martha wanted white ones for the girls and a dark one for her son. The neighbor brought back what was available, one white and two dark caskets.

Neighbors arrived early on the morning of July 25, 1911. The children’s bodies were washed and dressed with clean clothes. Three graves were dug southwest of the house. Then neighbors formed a procession from the house to the gravesite. A collection was later taken for a grave marker when Heinrich’s Immanuel congregation back at Canova heard of the tragedy. A stone was selected and the names and birthdates of the three children were cut into the stone. Written in German at the bottom of the stone are the words: all three died on July 24, 1911.

The rest of 1911 wore on with a sameness that Martha had never known. Every time she left the house, her eyes focused on the mound of dirt over her children’s graves. She could not stop the tears, nor did she want to. Prairie isolation added to her struggle. No one else spoke her native language of Switzerland. Her neighbors spoke Scot, Dane and some Norwegian. She believed, or perhaps she hoped, that her husband would realize that living there would be difficult and questionable. It was not true that rains follow the plow.

She longed for Iowa and Minnesota, but when Maria Martha Zurcher married on January 3, 1894, she made a promise to submit to her husband and obey him (und ihm gehorchen). God would expect her to keep that promise. She no longer found solace in caring for her Harrison Roses or the garden. Heinrich could not console her. Even the birth of their sixth child, Anna, would not bring back her smile.

|

| Steel cattle gates now protect what remains of the children’s grave. |

Martha became increasingly determined to leave the prairie, even if it meant breaking a wedding vow and disobeying her husband. Her husband sensed the seriousness of her resolve and made inquiries to church officials. A few weeks later he received a letter of call to become the pastor of St. John’s Lutheran Church in Aiken, Minnesota. He dispersed their possessions, the livestock, wagon and other implements to neighbors and they moved to his new parish in 1913.

The Koenigs would move once more to Hector, Minnesota, where Heinrich served as pastor from 1918 to 1926. Martha developed cancer and died in 1922. She had never returned to South Dakota. Because of failing health, Heinrich resigned his parish in 1926 and lived out the rest of his life in the homes of his children. He died in 1952.

Willa Cather writes of the prairie being in the process of reclaiming itself. The only evidence today of the tragedy in 1911 is a fence made of steel cattle gates around the gravesite and a broken gravestone. The scars made by Heinrich’s Sulky plow with its single 14-inch plowshare are gone. The dam that Heinrich built is filling with silt. Prairie grasses will finally overtake the place, a blessed part of the cycle of forgetting.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the March/April 2010 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Bertha (Koenig) Diemer was my grandmother. Her son, Eugene Diemer, was my father. This tragedy haunted my grandmother's life, and subsequently, my father's life, until their deaths.

If you feel inclined, please write me a note. I know little to nothing of my extended family.

Best,

Gretchen Diemer

907 315 2092