The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Mr. Bullock Goes To Washington

|

| Seth Bullock's chance meeting with Theodore Roosevelt was the beginning of a friendship that lasted until Roosevelt's passing. Bullock (front row, just left of the man in the gray suit) was a member of Roosevelt's so-called "Tennis Cabinet," a group of close friends and informal advisors who were received at the White House on March 1, 1909, the last day of Roosevelt's presidency. |

Seth Bullock arrived in Deadwood on August 1, 1876, the day before Jack McCall shot Wild Bill Hickok in the Nuttall & Mann Saloon. With so much excitement in the air, it’s not likely anybody paid much attention to him as he parked his wagon on the muddy main “street” and commenced auctioning off the goods he’d brought with him from Montana Territory. Bullock family lore has it that he sold a large number of chamber pots, which means Deadwood took a small step forward from its uncivilized, mining camp ways that day.

Above and beyond that contribution, no one man did more than Seth Bullock to hurry Deadwood along on its fitful journey toward respectability. He was appointed Lawrence County’s first sheriff in 1877, and by doing a credible job in a volatile time he gave the Northern Hills its first taste of law and order.

Bullock’s more important contributions to Deadwood’s long-term prospects were as a businessman and civic leader. The Star and Bullock Hardware Store, operated with his partner Sol Star, was a fixture on Main Street. Bullock also recognized that Deadwood would need to diversify its economy if it expected to survive once the gold rush was over. He invested his own money in the cause, not always with favorable results, and was “the loudest and most persistent” advocate for a Board of Trade, the equivalent of a modern economic development committee, wrote David Wolff in Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman.

Bullock and Star invested beyond the city limits as well. They acquired 160 acres along False Bottom Creek with the intention of establishing a dairy farm. When that didn’t pan out they moved farther north, purchasing land at the confluence of the Belle Fourche and Redwater rivers, where they established the S&B Ranch. In time that investment paid off in an entirely unexpected way, and sent Mr. Bullock to Washington.

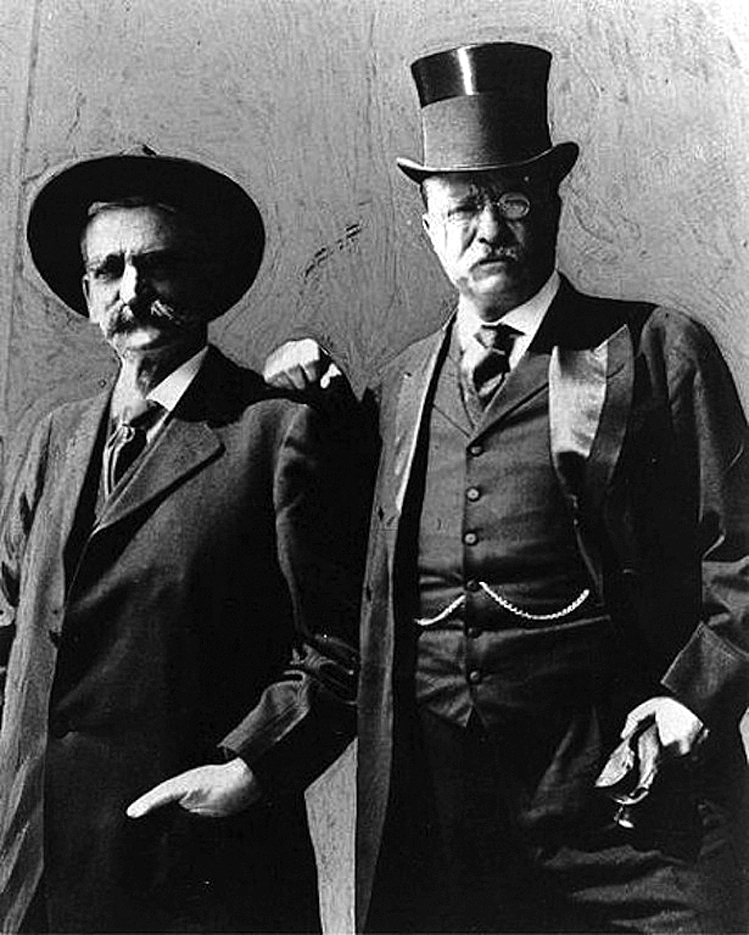

|

| Seth Bullock (left) and Theodore Roosevelt met on the banks of the Belle Fourche River. |

Theodore Roosevelt was a sickly, often bed-ridden child who spent his adult years making up for lost time. His quest for vigorous, manly adventure led him, in 1883, to try buffalo hunting in the Badlands of Dakota Territory. He was so taken with what he found he decided to buy a ranch in the region, and the very next year it became more than an investment. Disillusioned with politics, and in the wake of great personal tragedy — his mother and his wife died on the same day — Roosevelt told friends he was going to retire in Dakota.

Roosevelt’s Elk Horn ranch, on the Little Missouri River north of Medora in today’s North Dakota, was a bust financially, but he gained far more than he lost in Dakota. He embraced the West’s rugged ways, and cowboys as kindred spirits, and in so doing rediscovered himself. Before long he was back in public office, this time as sheriff of Billings County.

“As he grew older, Bullock liked to recount tales of the old days, and in particular, he enjoyed stories that drew Roosevelt into the narrative,” wrote Wolff. As Bullock remembered it, he and Teddy met about that time, while each was separately tracking the same trio of horse thieves. This story is in most accounts of Bullock’s life.

Roosevelt told a less colorful tale to his son Kermit. After resuming public life back east, Roosevelt was appointed to the United States Civil Service Commission. He returned to North Dakota and the Badlands on commission business in 1892; his next stop was to be the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Roosevelt chose to mix business with pleasure — his notion of pleasure, anyway — and make that leg of his journey on horseback, by way of Deadwood, which took him across Seth Bullock’s place.

“When Roosevelt and his companions crossed the Belle Fourche River, they encountered a cautious Bullock,” wrote Wolff. “As Roosevelt admitted, his party looked out of place, ‘exactly like an outfit of tinhorn gamblers.’ Once they exchanged introductions Bullock became much more cordial, and … this simple meeting initiated what would become a lifelong friendship between Roosevelt and Bullock.”

There was more than friendship on Bullock’s part, according to Kermit. “Seth Bullock was a hero-worshiper, and father was his great hero,” he recalled. Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most strident voices calling for war with Spain over Cuba, and when it came to pass in 1898 he rushed to volunteer. Bullock soon followed suit.

Melvin Grigsby, South Dakota’s attorney general, was commissioned as a colonel and placed in command of the Third Cavalry Regiment, which was slated for service in Cuba. Grigsby recruited Bullock to command Troop A, and Bullock in turn signed up 84 volunteers, mostly miners and cowboys. They left the Hills in high spirits, confident that they would make short work of the Spanish, and wherever their train stopped on the journey east, “people cheered, bands played, and food appeared,” wrote Wolff.

Which all went for naught. Roosevelt and his Rough Riders earned lasting fame in Cuba; Troop A, meanwhile, was still training in Georgia when the war ended. Bullock and his men were sorely disappointed by this turn of events, but his service did earn him nationwide publicity, “as a man of the frontier, a no nonsense pioneer,” wrote Wolff. It also cemented his bond with Roosevelt. When Roosevelt was named vice-president on the ticket with William McKinley in 1900, largely on the basis of his wartime reputation, he asked Bullock to accompany him on a campaign swing through the Dakotas and Montana.

Roosevelt loathed the largely ceremonial office of vice-president, but fate soon relieved him of the burden. An assassin’s bullet cut William McKinley down in 1901, and Theodore Roosevelt ascended to the “bully pulpit,” as he famously characterized the presidency. He liked the job so well he ran on his own in 1904, and when he won, Seth Bullock had a corker of an idea: round up a posse of real western cowboys, head for the nation’s capital and ride in his good friend Teddy’s inaugural parade.

|

| Bullock (front row, seventh from left), Tom Mix (front row, third from right), Fred Wilson (middle row, far right) and the rest of Bullock's Brigade rode in the inaugural parade and showed the folks in Washington what real live westerners looked like. |

Bullock’s Brigade, as they came to be known, “are not dime novel heroes or stage robbers,” wrote Bullock in his newspaper account of their trip. “They are cowboys, and as such are the real article, and the reason they [went to Washington] is because this was the first inauguration of a man who knows them.”

Fred and Charlie Wilson, ranchers from Harding County, were among the 60 men Bullock invited on the grand adventure. “They also picked up a few people along the way,” says Fred’s grandson, Fred Wilson, of Belle Fourche. “One of them was Tom Mix, before he got famous for making movies. He got to talking to them [during their stop in Chicago] and he decided to join up.” Mix had also volunteered for service during the Spanish-American War, and like Bullock, he never made it overseas before the guns were silenced.

Fred Wilson the elder wrote an entertaining account of the Washington trip in the 1950s. Curtis H. Satzinger, the long-time printer for the Belle Fourche Daily Post and Weekly Bee, kept a copy which his daughter, Rita (Satzinger) Edwards, found while going through his papers after Curtis’ death.

“There was a large crowd to see us off [from Deadwood],” wrote Wilson. A delegation of Wyoming cowboys joined the group in Edgemont, “and to say they were a lively bunch would be putting it mildly.” Some of their fellow passengers, a group of “Eastern ladies” in particular, were afraid to go into the dining car when the rough hewn cowboys were around, but before long they were charmed by the Westerners’ banjo and guitar serenades.

Bullock and company were given a tour of the city when they stopped in Chicago, and a large, raucous throng greeted them upon their arrival in Washington on March 2. Their horses had been shipped in advance, and the cowboys were disappointed to discover that their animals were in “pretty tough shape” after the long journey east. That couldn’t be helped, so they saddled up and set off toward the Washington Monument for some exercise and a little shockingly cruel “fun.”

“A large crowd followed us out there, many negroes among them, and we had great fun roping them as they ran from one side to the other,” wrote Wilson. “One negro … took exception to the fun we were having. He came out of the crowd … [but] we never knew what he intended for just then Jim Dahlman, of Crawford, Neb., who later became the mayor of Omaha, dropped a rope over his head and pulled him to the ground.”

Such were the times that no one chastised Bullock’s boys, or even remarked upon this behavior. Quite the contrary, wrote Wilson. Everywhere they went in Washington they heard, “‘You boys are alright. The president has vouched for you.’”

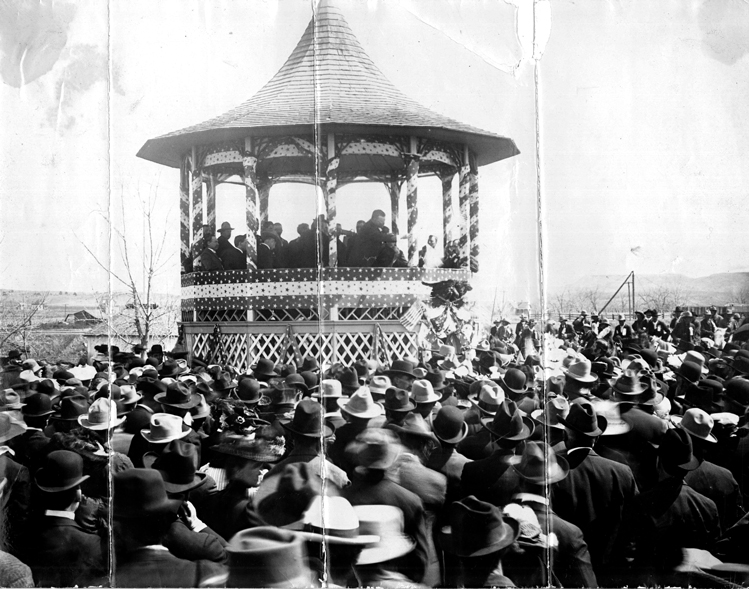

|

| President Roosevelt visited the booming cow town of Edgemont in 1903 and addressed the crowd from a bandstand that still stands in the city park today. |

Inaugural day dawned bright and clear. Roosevelt delivered his address, then took his place at the parade’s head. More than three hours passed before Bullock and company got their chance to promenade, by which time, “interest in the parade had perceptibly begun to wane,” according to a newspaper account. “It was thoroughly awakened, however, by the arrival of the Cowboys, who made only a pretense of keeping in line and flirted with every pretty girl who would look at them twice.”

This was the first time back east for many of the cowboys, but they sure knew what city folk wanted to see. “Lassoes hung from the pummels of their saddles and pearl ebony six-shooters stuck out aggressively from holsters suspended from their belts,” reported the newspaper, and at their head rode the quintessential westerner, “Captain Seth Bullock, who sat his horse as if he was in an easy chair, with his long moustache twisted by the wind and his left arm resting akimbo on his hip.”

“We were given a great ovation … from building after building and stand after stand as we rode up [Pennsylvania] Avenue, until we finally came in sight of the presidential stand,” Wilson recalled. “And there was Teddy, leaning out over the railing, and as we passed he shouted, ‘You’re alright, boys! I’ll see you later!’”

Roosevelt received the brigade at a White House luncheon later in the week. He introduced the boys to his family and conducted them on a tour, which ended in the State Dining Room. “‘Boys, I’ve got to bid you good-bye as the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee has been waiting to see me,’” said Teddy after an hour. “‘But I want to assure you, I have had many delegations in the White House, but none more welcome.’”

Bullock and the cowboys apparently worked all the wildness out of their systems before they reached Washington. “Compared with the noise made by the plug-hat-and-boiled-shirt political clubs, the cowboy brigade was Quakerish and decorous,” wrote Bullock. The astonished manager of their hotel agreed, saying they behaved, “like a Sunday School Teachers Convention compared to some of the other delegations entertained by him.”

Cowboys can only be good for so long, however. Some of them had to sell their horses in Washington, “so they would have enough money to get home,” wrote Bullock. “[Others] wanted a little cash to blow in New York, where they were going to stop before they started back to the range.”

After Theodore Roosevelt died in 1919, Seth Bullock erected a memorial to his hero on Sheep Mountain in Deadwood. For Wilson and the other cowboys, the monument paid tribute to a man they admired and served as a reminder of what was “the greatest event of our lives,” he concluded. “Many of the boys have crossed over the Great Divide, but there are those of us whose thoughts go back to those eventful days when we helped one of the greatest of our presidents, and took part in the greatest and grandest and most spectacular inauguration in history.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2013 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thank you for sharing it with us!

Bill Stevens

Sioux Falls, SD