The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

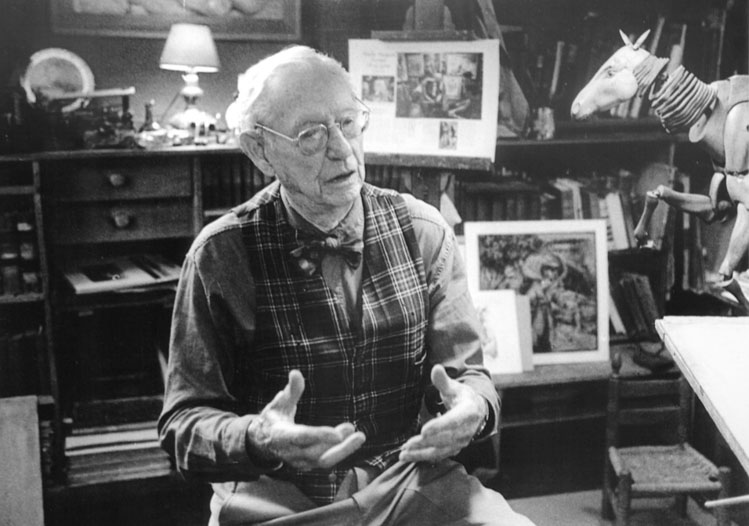

Our Case for History

|

| Leland Case lived and worked around the world, but always considered South Dakota home. |

Young South Dakotan leaves home, heads east to Chicago, earns a masters degree in journalism at Northwestern University and lands a job writing for the New York Herald’s Paris edition. The year is 1927 and he loves Paris, where he interviews Charles Lindbergh just after the aviator makes history by flying solo across the Atlantic.

Conventional wisdom might tell you the South Dakotan would never return to his home state after Paris, might not even give South Dakota another thought. But there was nothing conventional about Leland D. Case. After a year in France, he was back in the Black Hills, researching a man he considered a true Christian martyr, Methodist preacher Henry Weston Smith, found murdered outside Deadwood in 1876. Most historians believe Smith’s attackers were Lakota defenders, although alternative theories have circulated over the years. In 1929 Case published a pamphlet about Preacher Smith, read widely by locals and Black Hills travelers alike. If the name Preacher Smith still resonates among South Dakotans, Case deserves a big part of the credit.

“If you put Leland Case on an unchartered jungle island at midnight,” said his friend and colleague Herman Teeter, “he would discover a Methodist connection by dawn.”

That might surprise contemporary Leland Case fans who think of him primarily as a historian of the American West, or perhaps as a newspaperman and national magazine editor. And Case does have fans, more than three decades after his death, in part because he left significant legacies on two South Dakota university campuses.

For all that, however, he is regularly confused in discussions for his older brother, Francis H. Case, who represented South Dakotans in Washington, D.C., for 25 years as a Republican member of the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate.

But back to the Methodist Church. That was the institution that brought this remarkable family to South Dakota from Iowa in 1909, when Leland’s father, the Rev. Herbert Case, accepted a position at a Sturgis church. Leland, 9 at the time, never forgot the trip, crossing the vast treeless prairie by train. His family had arrived in the West. That meant two things — adventure and treasure. He found both when the Cases took up residence on a little farm at Bear Butte’s foot. Leland and Francis, sometimes accompanied by one or more of their three sisters, explored the butte’s draws and scaled its heights, hunted small game and found souvenirs that included cavalry buttons and artillery remnants from nearby Fort Meade maneuvers.

The Cases became friends with their neighbors, the Bovees, who ranched Bear Butte acreage. The butte was sacred ground to many Great Plains Native peoples, but in those years federal law forbade practice of Native religions. The Bovees snubbed their noses at the government, said the butte was theirs, and any Native people were welcome to pray and participate in religious ceremonies. It was South Dakota defiance of federal policy at its best. The Bovees’ young neighbor, Leland, grew up to write of the Lakota culture as something alive in the contemporary world, not just historical memory, in ways that would startle national audiences in coming years.

|

| Case worked to establish The Westerners, clubs across the nation dedicated to study and celebration of the Midwest. At a Westerners function in Hot Springs, he displayed a bison skull, the symbol of the organization. |

The Case family later lived in Mitchell, Hot Springs, Spearfish and Rapid City. Not surprisingly, the children grew up to enroll at South Dakota’s Methodist college, Dakota Wesleyan at Mitchell. That included Leland, although after a couple years he transferred to Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. He graduated from that school but then, as always, headed back to the Black Hills. He wrote for the Rapid City Daily Journal (Francis had bought into the paper’s ownership) and then the Lead Daily Call before Northwestern University beckoned. By this point it was apparent that Leland and Francis had evolved into remarkably similar men — journalists professionally, and thoroughly engaging personalities who were persuasive both in person and in print. What’s more, each was fearless. Francis’s sometimes-adversary in the U.S. Senate would be Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson, and often colleagues cowered before Johnson. Not Francis Case. As for Leland, if he found himself or an institution he was part of disparaged, he’d likely show up on the critic’s doorstep and ask for an explanation.

Among institutions sometimes disparaged in the 1930s was Rotary International, the network of community service clubs. In 1930, a year after publication of his Preacher Smith pamphlet, Leland began writing for The Rotarian, a Chicago-based magazine sent to club members worldwide. Within months he was named editor and for nearly 20 years published quick-paced features, delving into everything from sports to science, but mostly themed around the idea of ordinary people doing extraordinary things for their communities. As Americans struggled through the Depression, Case believed it was vital for everybody to polish skills that would benefit the community as a whole — very much in line with Rotarian philosophy. That felt small-town and unprofessional to some Americans who considered themselves well educated and perhaps elite, including author Sinclair Lewis. Lewis had dismissed Rotary clubs a decade earlier in his classic novel, Babbitt, so he was perhaps overdue for a visit from the editor of The Rotarian. According to Jarvis Harriman, who published a fine Leland Case biography in 1994, Lewis told Case sure, come by for a talk, fully intending to send the editor on his way after a few minutes. But Lewis found Case so engaging that the men talked for hours, and Lewis agreed to write a story for The Rotarian. It was a classic Leland Case encounter.

Other writers came much easier, including South Dakota poet Badger Clark, who found a national audience through The Rotarian. Babe Ruth, H.G. Wells, and Winston Churchill were published during Case’s time at The Rotarian’s helm. Case considered it imperative that Albert Einstein’s byline should appear in his magazine. He met the scientist at Princeton, New Jersey, and found him courteous but leery. Other American journalists and editors had mangled his words — not intentionally, Einstein knew, but because he thought in German and his concepts were, to say the least, complex. Case proposed what he called a “new idea” in magazine composition.

He would submit questions in writing to Einstein, involve a translator, and build a feature from the scientist’s typed responses, unaltered. Einstein joined the long list of people who found it impossible to say no to Leland Case. “Quite frankly,” Case later wrote, “I recall working up no feature that generated more personal satisfaction.”

|

| Leland Case's artifacts are preserved at Mitchell's Dakota Discovery Museum, the former Friends of the Middle Border Cultural Center advanced by Case in the 1930s. |

But even when working with personalities who would go on to be regarded internationally as 20th century giants, Case’s thinking never strayed far from South Dakota. He traveled home regularly, accompanied by his wife Josephine, a musician and teacher he met in Chicago. In South Dakota, Case worked on his brother’s political campaigns and spent time, in the 1930s, in Mitchell successfully advancing his idea of a Friends of the Middle Border cultural center. Part of the Dakota Wesleyan campus, it would preserve the arts, humanities and artifacts of the Great Plains which, at the time, appeared in danger of blowing away completely during the Dust Bowl. Carl Sandburg and Laura Ingalls Wilder, fellow Midwestern writers who felt the same urgency for cultural preservation, agreed to sit on an advisory board.

In the 1940s Case wrote a popular Black Hills travel guide, revised and reprinted over the years by the Black Hills, Badlands and Lakes tourism association. The same decade, with Chicago friend Elmo Watson, Case founded The Westerners, a network of clubs (or “corrals”) across the country where members met, ate, drank and swapped tales about the Old West. Amateur historians who discussed family lore were as welcome as academics and published authors. Many corrals still celebrate the West today.

In 1950 Case left The Rotarian and soon had an idea for National Geographic Magazine. How about a feature combining Black Hills history and travel tips? National Geographic wasn’t about to say no to Leland Case writing about his favorite place. It assigned him a photographer. Case visited significant locales and looked up old friends, including the Bovee family at Bear Butte.

National Geographic ran the feature in its October 1956 issue. Rather unfortunately, the magazine titled it “Back to the Historic Black Hills,” a play on Doris Day’s popular Black Hills song three years earlier. The story’s content was less playful. Of the region’s history Case noted: “A single lifetime bridges it — Custer to Coolidge, gold stampede to uranium rush, Sioux travois to jets at Ellsworth.”

But most striking about the feature, read more than 60 years later, is Case’s anecdote about a contemporary Lakota man, fined $25 in court for some infraction. Case quoted the man telling the judge, “I owe you $25. You owe me for the Black Hills. When you pay me, I pay you.” Nearly two decades before the matter exploded into national consciousness, who but Leland Case was telling Americans that the federal government had seized the Black Hills and owed compensation?

By the time the story was published, Case was once again behind an editor’s desk in Chicago, producing a new Methodist magazine called Together. Under Case’s leadership it grew quickly to a circulation topping a million. Like The Rotarian, its writing style was easily accessible and fast moving. The magazine featured profiles of personalities both well known and every day. Tips for activities that families could enjoy together were a staple.

In 1962 Case’s world changed when his brother, Senator Case, died in office, hit by a heart attack. Leland was 62 years old and the loss seemed to tell him that if he had projects he hoped to wrap up, now was the time. Over the next few years he began looking for a college or university that would work with him to establish a Western studies library.

Case retired from Together magazine in 1965. He and Josephine spent most of their time in Tucson, Arizona, partly because the climate was good for a respiratory condition Leland developed, and also because they liked Arizona. But Case’s search for a school that would support his project drew his thinking back to South Dakota, once again. He would contribute his personal history library, materials about the Case family (including some of his father’s sermons) and dollars to establish a history scholarship. He would encourage colleagues to donate their personal libraries, too. Case struck a deal with Black Hills State in Spearfish, in the center of the region where significant Western history played out.

|

| Case's personal office has been recreated at the Dakota Discovery Museum in Mitchell with artifacts and books brought from Tucson, Arizona. |

Case told Spearfish newspaperman Art Mathison, “I was in college here, even though nobody knew it.” His father worked in Spearfish in 1917, Leland’s junior year in high school, before the community had a high school. As was common practice in state college towns then, students wishing to pursue high school diplomas were granted credits if they succeeded in college courses. Case was proud of his success, academically and socially, among older students, and the experience seemed to spark the love he always had for colleges and universities.

The Leland D. Case Library for Western Historical Studies, located within Black Hills State University’s E.Y. Berry Library-Learning Center, was dedicated in April of 1976. Case delivered a heart-felt speech, calling for volunteer “field historians” who would help determine “how bits and pieces of Hills history may be saved from fire, flood, and the city dumps.” Like the old editor he was, he had story tips for historians willing to tackle overlooked history, including the Black Hills’ many connections to the Alaska gold rush. Another story waiting to be told, he said, was how the Black Hills National Forest pioneered federal policy about scientific tree cropping (today his library houses the Black Hills National Forest Historical Collection). Later, Case told Mathison that historians might be better off forgetting Wild Bill Hickok, Calamity Jane, Poker Alice and Fly-Speck Billy, and focusing on more important figures.

Leland and Josephine visited Spearfish several times after the library’s opening, and Black Hills State awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1980. Case didn’t stop researching and writing until the very end of his life. He died in 1986, at age 86, in Tucson.

There are spots across South Dakota where anyone who knows Leland Case’s story can’t help but sense his spirit: Bear Butte tops the list, along with any clapboard Methodist Church on the prairie, and any ridge overlooking the Middle Border plains that recovered beyond his hopes after the Dust Bowl. But a special spot is his recreated office in the Dakota Discovery Museum, the modern name for his Friends of the Middle Border center in Mitchell, on the Dakota Wesleyan University campus.

There are furnishings, photos and artifacts from his Tucson office, and best of all some of his books that reveal his many passions. Volumes on the shelves include Black Elk Speaks, Louis L’Amour novels and books detailing vigilante justice, Chicago history and South Dakota’s role in World War I. And not surprisingly Case collected books that approached the Methodist Church from every angle — John Wesley’s life, the church’s roots in England and development across America, Methodist poets, and even a guidebook to Methodist tourism.

“Leland’s interests were vast and varied,” says Bobbi Sago, special collections librarian and archivist for the Case library at Black Hills State. She calls the library “a tremendous legacy from a fascinating man. It is a wonderful gift to the residents of South Dakota.”

Case was a driven man who understood American culture and who never doubted that South Dakota’s contributions were important to the nation’s character. His brother’s name may be more prominent in state history. On the other hand, Leland Case sat at his typewriter and composed much of that history.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2017 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments