The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Remembering a Small-Town Boy

May 4, 2020

|

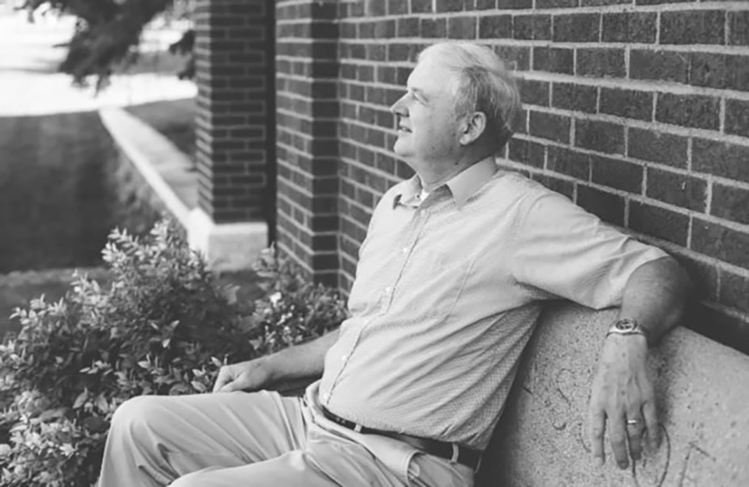

| John E. Miller was a professor at South Dakota State University from 1973 to 2003 and a longtime historian of South Dakota. He passed away on May 1. |

My high school friends were giddy before we began our first semester of college. No more waking up before noon. With the newfound freedom of assembling our own schedules, everyone sought classes that met in the afternoon, leaving mornings set aside for quality time asleep.

When I was a freshman in the fall of 1998, I signed up for History 152: United States History Since 1877, which met three days a week at 8 a.m. I harbored some doubts that maybe I should be following the lead of my friends, but I also an interest in history and maybe a slight desire to rise and shine. Not a day has gone by in the last 22 years that I’ve regretted the decision.

The teacher was Dr. John E. Miller. Little did I know at the time that he was one of South Dakota’s preeminent historians. All I knew after those first few classes was that he was a small-town guy who loved American history, just like me.

Dr. Miller died on Friday, May 1, of an apparent heart attack at his home just a few blocks from campus in Brookings. He was 75. His death leaves a gaping hole in the study of South Dakota history that will take years to mend — that is, if it can ever be truly filled.

I remember very clearly the day, just a few weeks into class, when he asked how many of us grew up in what might be considered a “small town.” He asked us to think about how our hometowns were laid out and had us sketch them. Then he put his own drawing of Monett, Missouri, on the overhead projector. (Monett was one of his hometowns; he lived in several due to his father’s work as a Lutheran pastor.) We saw Main Street running across the page with a schoolhouse at one end and railroad tracks running perpendicular on the other. It was a perfect T. That’s exactly what Lake Norden looked like, and, I suspect, the hometowns of 90 percent of my classmates. History tends to be unfairly characterized as boring, but this was his way of engaging the class and making history become real, a method for which he had a true knack. Fellow historian and former student Jon Lauck has recalled the day when Miller got down on one knee in front of the class and lamented, “Say it ain’t so, Joe!” when discussing Shoeless Joe Jackson and the Black Sox scandal of 1919. I don’t recall those particular theatrics, but former students know that yes, that’s exactly what he would have done.

After that, I signed up for every Miller class I could: U.S. Between the Wars, U.S. Since 1941, American Economic History and Methods and Philosophy, for which I wrote a paper comparing stories that appeared in major newspapers to what was being said on the Nixon tapes. Oddly, I never took History of South Dakota from him, but it proved to be a stroke of luck in the long run. While working on a master’s in history at the University of South Dakota, I took the course with Herbert Hoover, Miller’s counterpart and another extremely knowledgeable South Dakota historian who sadly passed away just 14 months ago. Both of them helped me as I wrote my thesis on Richard Kneip and South Dakota politics in the 1970s.

I learned a little more about Dr. Miller through every class. He’d gotten his Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin, where he wrote about that state’s Progressive governor Phil LaFollette. He’d been in Vietnam. He’d had heart problems before (I remember him telling me how he ate fewer Big Macs for lunch and played more pickup basketball in The Barn). And he loved baseball, especially the St. Louis Cardinals and Stan Musial, the team’s star of the 1940s and 1950s. That led to a lot of ribbing when he discovered my affinity for the Chicago Cubs, longtime rival of the Cardinals. Over the weekend, as news of his sudden death struggled to sink in, I thought of my favorite Stan Musial stat: he collected 1,815 base hits in home games and exactly 1,815 hits in away games. “Did Dr. Miller know that?” I wondered, as I stared out of my kitchen window. Of course, he would have known that.

After a year of teaching in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Miller and his wife Kathy arrived in Brookings for what was supposed to be a short-term job at SDSU. But the family settled right in, and Miller seamlessly became part of the South Dakota fabric.

That’s evidenced in the books he produced. Looking for History on Highway 14 came about through a desire to study small-town life, searching for comparisons or commonalities, as he told fellow historian and former student Jon Lauck. Searching for some sort of geographical organization, the idea of writing about the towns strung along Highway 14 emerged. “It has the capital, the state university, the state fair, the “most historic spot in South Dakota” (Fort Pierre), Wall Drug, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Harvey Dunn, Theodore Schultz (born, at least, in Arlington). It just seemed like a no-brainer,” he said.

More study and lengthier writing on Laura Ingalls Wilder came out of his Highway 14 research. Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little Town: Where History and Literature Meet and Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend appeared in the years following his Highway 14 book.

His final published article, which you can read here, reflects a passion I saw firsthand when he spoke at the last Dakota Conference at Augustana University in Sioux Falls in 2019. Caroline Fraser published Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder in 2017, and Dr. Miller — the author of several articles and books on Wilder — had a lot to say about it. Miller was famous for handouts, and he did not let us down. We got page upon page of passages photocopied from Fraser’s book — some underlined, some highlighted with notes filling the margins — to help navigate his way through fully scrutinizing the arguments she made. As I recall, he didn’t quite finish. He was also famous for tangents.

To say he retired in 2003 is using the term loosely. I’ve never seen anyone busier with research, interviewing, traveling, reading and writing. Long after I left college and landed at South Dakota Magazine in 2007, he never failed to send his newest books, including the one he’d talked about as an idea 20 years before: Small Town Dreams: Stories of Midwestern Boys Who Shaped America. To me, this was the book he was born to write. There are chapters on Bob Feller, Mickey Mantle, Johnny Carson and Ernie Pyle, among others — all important figures who were perhaps made so by their Midwestern upbringing.

It seems that another chapter in this book could have been written about John Miller himself, for he was at heart a small-town Midwestern boy who certainly shaped South Dakota, if not the entire Midwest and beyond. He helped us understand who we are as South Dakotans, and why being from here matters. Our state will never be the same without him, but thank God we had him, at least for a little while.

Comments

John loved to share his passion for history with people and South Dakota, SDSU and thousands of his students and readers are better because of it.

A slight edit -- you meant Herb Cheever, not Herbert Hoover, as the other SDSU professor. He was a talented, driven man, active in the SD Democratic Party as well as on the Brookings campus