The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Rocky Road

|

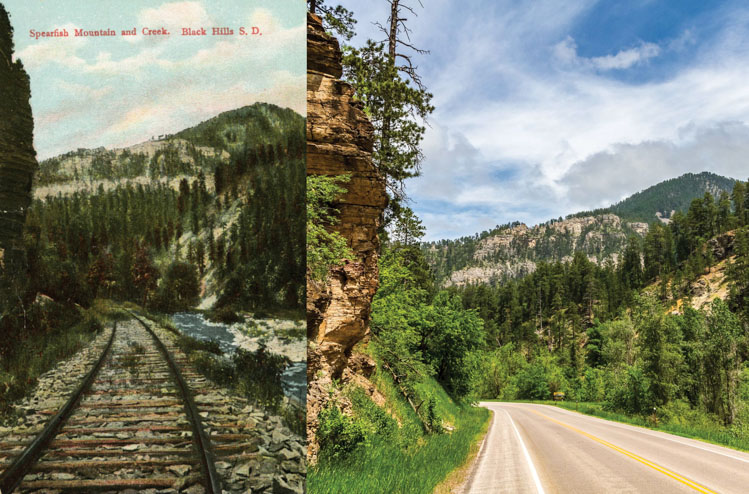

| In some places, the modern Spearfish Canyon Highway closely follows the route of the old Spearfish Canyon railroad, especially approaching Spearfish Mountain from the south. |

THE JOKE ALREADY felt stale when I was a teenager in Spearfish: “No one grows up on the wrong side of the tracks here because there are no tracks.”

No tracks, no whistles, no rattling train cars through Spearfish nights. When the town lost rail service of any type in 1933, its population was under 2,000, yet Spearfish ranked as the biggest community in the United States where no locomotives rolled. Most people didn’t seem to care. During the same decade in which Spearfish said goodbye to trains, it gained mail and passenger service by air and developed an outdoor drama (Black Hills Passion Play) that would soon draw 100,000 travelers annually who were “tin can tourists”— packed into automobiles.

Within just a few years, the Spearfish Canyon railroad became a Black Hills legend: the train that had to be tied down at stops so it wouldn’t roll away down the steep grade, a friendly rail service that dropped off passengers at their favorite fishing spots in the morning and picked them up again in the afternoon, the transportation that President Theodore Roosevelt selected for his sons so they could access the rugged West.

This summer I spent two beautiful but futile days searching for signs of the railroad in the canyon’s heart. I splashed along Spearfish Creek’s banks hoping to see just a piece of one of the 33 railway bridges that crossed this water and its tributaries. Nothing. The railroad boasted that by necessity it built remarkably well in the canyon, that “ties are bedded in rock the whole way.” Probably so, but in the heart nothing survived a railroad salvage contractor in 1934 and the relentless erosion that is the essence of any living canyon.

Out of the canyon’s heart, on its fringes, I’ve seen photographs of surviving abutments for great trestles that dropped trains off Bald Mountain and into the canyon, but I haven’t found them myself yet. In Spearfish a cycling and walking trail utilizes the old rail bed. A feature all Spearfish Canyon highway drivers recognize is a cut through which they pass 3 miles from Spearfish, considered by many to be the canyon’s north entrance. Originally, the cut was blasted for Grand Island & Wyoming Central trains (later known as the Burlington & Missouri River, or just the Burlington).

The first locomotive steamed through that rock cut and into Spearfish in December of 1893. Engines had to be powerful to handle the steep grades but were limited to 25 mph when moving passengers and 15 mph when passenger cars and freight cars were combined.

The Burlington’s interest in the canyon stemmed from a series of proposed mines and ore processing mills that investors believed would utilize new technologies to extract gold and other precious metals. These canyon mines did indeed take form, but their production lives were short. The canyon railroad also carried passengers seeking tent camping, berry picking and steep hikes to spectacular vistas. There had been no outcry against sacrificing natural splendor to make way for mines and mills. Prior to the railroad, very few Black Hills people knew anything about Spearfish Canyon. Even in the town of Spearfish, only the most intrepid game hunters ventured into the canyon because its lower end was tightly packed with great boulders.

|

| Spearfish-bound passengers from Deadwood knew they were more than halfway to their destination at Elmore and that they had descended into the canyon proper. |

Thanks to the Burlington, Spearfish Canyon burst into consciousness. Modern South Dakotans don’t like reading early Black Hills historian Annie Tallent’s racist views, but it’s hard to dispute that in 1899 she wrote a perfect description of riding the rails through Spearfish Canyon: “A trip over this marvelous piece of mountain railway — up the dizzy heights to the extreme summit of Bald Mountain, around a labyrinth of lofty crags in perfectly bewildering curves, and a plunge down into and through the most beautiful canyon in the world (the Spearfish) — is a revelation of grandeur and beauty unsurpassed and the treat of a lifetime.”

Six years later passenger James Doyle wrote in Spearfish’s newspaper, the Queen City Mail, that the canyon, “has no common place in it. It everywhere plays homage to omnipotence.” And much of it could be observed, through all seasons, from the comfort of passenger cars. Changing seasons, others noted, could sometimes be experienced in a single day due to the variance of elevations along the route. It wasn’t out of the question for passengers to board at Deadwood in a spring mist, encounter drifts and even blowing snow in the canyon’s middle, then step into summer-like sunshine down the grade at Spearfish.

An industrial aspect of the line remained through its four-decade history, chiefly lumber and wholesale deliveries to Spearfish, and farm produce and livestock shipped up the hill from Spearfish. But by the time the railroad merged into the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy in 1904 there could be no doubt that excursions were the main function. Recognizing that the average patron was now more likely to board with family members than livestock, the line stressed safety. “The passenger takes no risk when he rides,” read company publicity. “The history of the line proves this. Collisions are out of the question because there’s nothing with which to collide. One train has the canyon to itself all day.”

While no other train could cause a wreck, engineers had to watch for boulders that came bounding down the canyon walls. There’s no record of one hitting the train, but now and then passengers were asked to climb out and help clear the tracks of rocks.

It was about 40 miles one way between Deadwood and Spearfish, but just as often the rail line was referred to as a 32-mile run — the distance between Englewood and Spearfish. In the early 1900s, round trip tickets cost about $2.50. Passengers boarded at Deadwood’s Depot 47 on Sherman Street, a couple blocks east of the Franklin Hotel, in the morning and arrived in Spearfish early that afternoon. The Spearfish depot was a wood frame structure where the community’s main fire station stands today, on Canyon Street. By mid-afternoon the train had been turned around and was headed back up the canyon. Today, almost universally, the railway is recalled for its Deadwood to Spearfish and back runs, strangely inefficient because the geography forced the engine to actually steam in the direction opposite of its destination much of the trip.

|

| Remnants of trestles that were part of the Seven Mile Bend can still be found near Annie Creek. The train dropped (or climbed) 800 feet in elevation over those 7 miles. |

Less well remembered is the fact that passengers could disembark and connect with another Burlington train at Englewood. That route (today the Mickelson Trail) took them south through the heart of the Black Hills and, in many cases, out of the Hills to distant cities.

Spearfish Canyon developed as a destination in its own right with construction of overnight lodging early in the 20th century. Deadwood’s Glen and Doris Inglis first opened the Glendoris Inn (now the storied Latchstring Inn) mid-canyon at Savoy where the train passed dramatically over a trestle across Spearfish Falls. Later, Martha Railsback and Maude Watts journeyed into the canyon by rail, bought the inn and brought it to full fruition. Sometimes elfin-sized, bewhiskered gold prospector Potato Creek Johnny greeted rail passengers at the inn and played his fiddle late into the night.

The canyon railroad had a role in one of South Dakota’s boldest engineering and construction feats ever between 1909 and 1912. Homestake Gold Mine diverted creek water through Spearfish Canyon’s west wall by way of 23,862 feet of tunnels it cut through solid rock. The diverted water spun turbines in a new state-of-the-art plant at Spearfish, generating electricity that powered mine operations for the next 90 years. The canyon rail bed was a reference point that surveyors used in determining the tunnels’ course, and the rails delivered drills, laborers and supplies. Canyon rail passengers were among the first to notice Spearfish Creek’s diminished flow in the lower canyon after the power plant went online.

A bit later Homestake built a second, smaller hydroelectric plant in the canyon, with water mostly channeled to it through an above-ground pipeline. Today, people sometimes mistake the pipeline path, visible along a ridge north of Savoy, for the old Burlington bed.

In the 1920s, Spearfish Mayor James O’Neill advocated for an automobile road through Spearfish Canyon. In fact, his enthusiasm led him onsite to work with the road crew some days after funding was secured. This first version of the Spearfish Canyon highway opened with ceremonial dynamite blasts and a speech by Gov. William Bulow in August of 1930. Hard as it is to imagine today in narrow parts of the canyon, the highway and train co-existed for two years and nine months.

Then on May 20, 1933, according to railroad records, “Engineer Steinberg and Fireman Kaup” made what proved to be the Spearfish line’s final run. Three days later a raging Spearfish Creek wiped out rails and bridges. In July, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy filed a request with the Interstate Commerce Commission, seeking to abandon the line rather than rebuild. The Queen City Mail grumbled and Spearfish gasoline retailers stepped up to state they got better rates for customers when their product was delivered by rail. But the railroad had no difficulty documenting it was losing money, and called passenger service “not important,” because travelers preferred “moving principally over the highways.” That was exactly what Mayor O’Neill had sensed a decade earlier. The Commission authorized abandoning the lower 25 miles into Spearfish but told the railroad to continue serving mines in the Bald Mountain vicinity.

In coming years Spearfish leaders sometimes contemplated re-establishing a rail connection, not through the canyon but by way of a northward spur to Belle Fourche. Nothing came of it. Then in the 1960s the community decided it wanted to be an interstate highway town. Leaders were successful in getting Interstate 90 routed past town in the 1970s, just as new Catholic priest Father Eugene Szalay arrived. As a hobby, he sought out people who recalled the old canyon line and preserved their stories.

Apparently no one confessed to Father Szalay what the railroad knew: Poachers at least once “borrowed” hand cars to sneak out-of-season bucks from the canyon. Much of what the priest heard came from former employees who recalled their canyon railroading as a grand outdoor adventure. Roger O’Kieff, for example, was hired at age 14 and sometimes tied one of those hand cars to the back of the train. He was pulled along until spotting snow or rocks to be cleared away from the track. Then he cut himself loose to tackle the job.

That would have been a dream job for any teenager during the golden, but short-lived, era of railroading through Spearfish Canyon.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2019 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments