The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Searching for the White Mule

|

| Sheriff E.E. Sherman (center) displayed whiskey-making equipment on the steps of the Union County Courthouse after a raid in the 1920s. |

South Dakota jumped the gun on prohibition, passing a “dry” law more than two years before the 18th Amendment bottled up the nation’s booze business in 1920. What followed the 1917 South Dakota law and the later federal mandate uncorked a lengthy cat and mouse game. Moonshiners (the manufacturers) and bootleggers (retailers in Model As) became skilled at hiding stills and stashes from state and federal agents and the local law who worked night and day sniffing out the illegal white mule, as many called the homemade brew.

Nearly every South Dakota county and community had its covert booze operations, and most citizens with an occasional or unremitting itch for John Barleycorn knew where to find it. When the South Dakota constitution was drafted in Sioux Falls for a citizen vote in 1889, some wanted prohibition included. Fearful the emotional issue would influence the constitution vote, delegates wrote a prohibition amendment as a stand-alone ballot question.

Both the constitution and prohibition passed, and the 1890 South Dakota legislature framed a law making manufacture, transportation and sale of alcohol illegal.

Five years later, citizens had a change of heart and voted prohibition out. Swinging doors were oiled, shot glasses washed, brass rails polished and the state’s often vilified saloons were back in business.

But by 1916, better-organized dry factions - the Anti-Saloon League, churches and the Women’s Christian Temperance League headed for decades by Flora Mitchell of Brookings - succeeded in getting another vote that hoisted South Dakotans back up on the prohibition wagon. After considering a state-run liquor business in which state liquor agents would keep names and amounts purchased, legislative reason prevailed. Liquids sold as beverages could have zero percent alcohol. The edict was christened the “bone-dry” law.

|

| In 1917, Gov. Peter Norbeck signed a law creating the office of State Sheriff to more vigorously enforce federal prohibition laws. Lawmakers appropriated $3,000 to fund the effort. |

To enforce the law, the legislature created the Office of State Sheriff. Later, the 18th Amendment was passed and federal agents were assigned to the state. Even with these units, law enforcement could hardly keep up with the growing number of stills whose operators were merrily churning out and hiding liquor of varying quantity and quality.

Stills steamed away in caves, isolated shacks, cornfields, timber stands, sandy river islands and on isolated farms. Stashes of booze were found in post holes, automobile spare tires, souped-up cars, straw stacks, potato piles, seeder boxes, and even hollow cemetery grave markers.

Hiding the bottled booze was a challenge. Interestingly, post hole digging tools made cool, camouflaged repositories slightly larger than the round alcohol bottles, and post holes could be sunk in the least likely of places, like chicken houses. Weedy road culverts were handy. The augers of idle threshing machines made passable liquor cabinets.

Another clever hiding place was discovered in Brookings County. The county road grader operator discovered more than a dozen one gallon jugs of booze buried up to their corked necks among roadside weeds near Bruce. Opposite each buried bottle, a piece of white cloth was tied to the fence as a subtle marker.

Newspapers were splashed with stories of still or stash discoveries. In 1923, Meade County Deputy Sheriff Fred Westgate said illegal stills were so prevalent in West River country “one can hardly put his foot down without stepping on one.”

A Sisseton farmer sold his powerful homemade “medication” at a rheumatism clinic he founded. A remarkable number of Roberts County men were soon afflicted and sought treatment until the law intervened.

By the 1930s Hank Kempel of Sioux Falls had brought together a group of young toughs to distribute illegal booze trucked in from Al Capone’s Chicago monopoly, and local police were soon dealing with what they called “the Kempel Gang.”

|

| Verne Miller was a Beadle County sheriff who turned to bootlegging and organized crime. |

Dempster Mayor John DeWall cracked a wry smile in 1931 and appointed a committee to review applications from the five different bootleggers active in Hamlin County for a local distribution franchise. Committee members played along, but wanted samples.

The annual reports of the state sheriff show the extent of the problem. The 1923-24 report cites the arrest of 178 still operators. Concurrently, federal agents, county sheriffs and U.S. marshals were also barging in and breaking up bubbling sites.

After state deputy sheriffs raided the Schwenk farm in Yankton County on Dec. 7, 1921, two trucks hauled away a plethora of beer making gear, including “three testers, 800 quart cans of canned malt, 100 gallons of malt in barrels, twelve quarts Primo, nine cases hops, two bales of hops, three dozen packages of hops, twenty-one capping machines, one can sealer, one box hose holders, two gross cans, seven dozen packages gelatin, 800 pounds of bottle caps, fifteen packages of labels, 78 packages of rubber stoppers, two boxes of siphon hose and 100 pounds of shot.” The pellets were used to help clean particularly dirty beer bottles for reuse.

Later that year at a farm in Hutchinson County, officers arrested L. T. Kleinsasser, W. T. Warne and Peter Hofer, and seized one stove and feed cooker, two sacks of bottles, 300 gallons of mash, one sack of rye, one cooler coil, six barrels, one milk can, one bushel basket and more. Firearms, knives and brass knuckles were often found among the moonshiners’ assets. In a 1923 raid near Sisseton, the outraged moonshiner hurled a barbed fish spear at an officer, but missed.

As agents became more proficient at finding stills, moonshiners became more adroit at hiding them. Near Elk Point in late 1924, agents found a 10-by-40-foot cave in a cornfield covered with boards and dirt. The dugout held a 100-gallon capacity still to process 40 awaiting barrels of fermenting mash. Agents also found a six-burner kerosene stove, supplies of sugar, rye and yeast, and an impressive inside water well.

To enter a suspected moonshine cave near the town appropriately named Rumford in Fall River County in 1931, agents climbed down a ladder inside a well and squeezed through a wall opening where they found a 100-gallon still.

|

| Law officers often posed for news photographers with firearms and liquor confiscated in raids. This 1918 photo was taken in Brookings. |

More squalid still locations were hidden under hog houses, barn stalls and manure piles. At the Hamandberg farm north of Harrisburg agents found a trap door under a resting cow in a barn stall leading to an underground still. Caves under hog pens were particularly filthy. The dripping effluent percolating from above mixed with the mash, but these “mixed drinks,” did not deter sales. Another common secret ingredient was poison caused by lead from corrosive evaporation coils.

Agents often found mash with drowned mice, bugs and birds floating on top. And in some cases officers had to shoo chickens off mash barrel roosts, but most moonshiners didn’t operate this way. They considered their product among the finest available, such as the alcohol made the old-world way by Adolph Schelske of Parkston. His daughter Leona Pietz describes her father’s still in a book, Memories of a Bootlegger’s Daughter. Leona’s daily chore was to carefully stir the fermenting, bubbling mash.

The used mash from Schelske’s barrels was discarded through a pipe draining to a nearby stream where, Pietz wrote, the mash attracted and nourished happy fish that were later caught and eaten.

Moonshiner Bert Miller of Hill City was described as a “master distiller” by Carl West, the Minneapolis Prohibition Enforcement Department’s chief chemist in 1924. Moonshiners Miller and Schelske were just two of many South Dakotans who sought to perfect their brew.

As prohibition nationally and eventually in South Dakota was ending, federal and state agents raided two “super stills,” one in northern Clay County and another west of Sioux Falls. Both expertly engineered, leading officials to suspect Al Capone’s operation in Chicago may have provided financing.

The coming of the automobile was a bootlegger’s dream, expanding his territory and his carrying capacity. The largest auto liquor cargo ever found in South Dakota was on July 11, 1932, west of Huron. Officers counted 228 one-gallon tins of booze in Bernard “Bud” Bruns’ re-vamped 1932 Buick five-passenger coupe. They also confiscated his .45 caliber pistol and two glass jars filled with roofing nails to throw out and disable police cars during a chase.

Violence was a by-product of the business. Flandreau bootlegger Ira Dawson shot it out with two deputies in White, a small Brookings County town, in May of 1928. Dawson died en route to the Brookings Hospital. At the Chrisman farm near Redfield, bootlegger Chrisman ambushed and killed two agents.

Most state and federal agents were straight arrows, but bad apples did succumb to the lure of payoff money. Verne Miller, a personable, handsome World War I hero from White Lake, became Beadle County Sheriff in 1920, but soon turned south and became a hired killer for eastern mobsters. His killings put him on the FBI’s most wanted list, but his underworld enemies found him first.

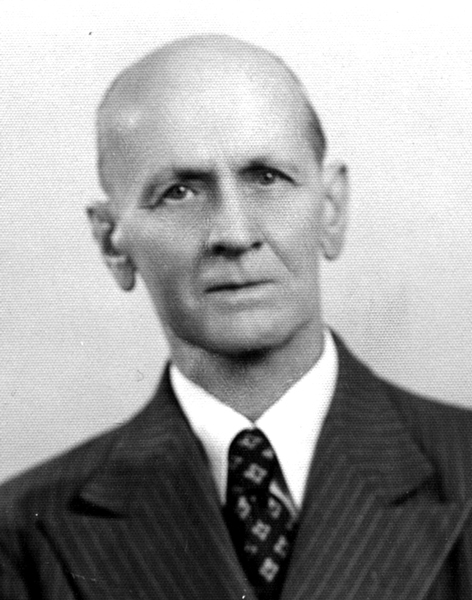

|

| Edward Senn was a newspaperman and a crusader for prohibition in South Dakota. |

The superstar of dry agents in South Dakota was Edward L. Senn, the crusading Deadwood Daily Telegram newspaper editor-publisher who became federal prohibition administrator in 1925 and served until national prohibition ended in 1933. He was tireless and often led raids by agents the press called “Senn’s Raiders.”

Senn’s heart must have been broken when national prohibition ended in 1933. South Dakota and its bone-dry law continued for nearly two more years, much to the chagrin of wets.

The state became an island in a sea of sloshing liquor in surrounding states. Calling a special legislative session to end the bone dry law was made more complicated because Governor Tom Berry feared a just-passed gross income tax vote might crop up in a special session along with the prohibition question.

The wets finally won out in April of 1935, and the state’s journey astride the white mule was over.

Editor’s Note: Chuck Cecil is a longtime South Dakota author and newspaperman. These stories are condensed from his book Astride the White Mule, the only book ever written about the state’s prohibition years. The 200 pp. softcover is available for $15, plus $3 shipping/taxes, from Books, P.O. Box 608, Volga, S.D. 57071. This article is revised from the July/August 2012 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments