The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Explorers, Cowboys and Indians

May 17, 2016

|

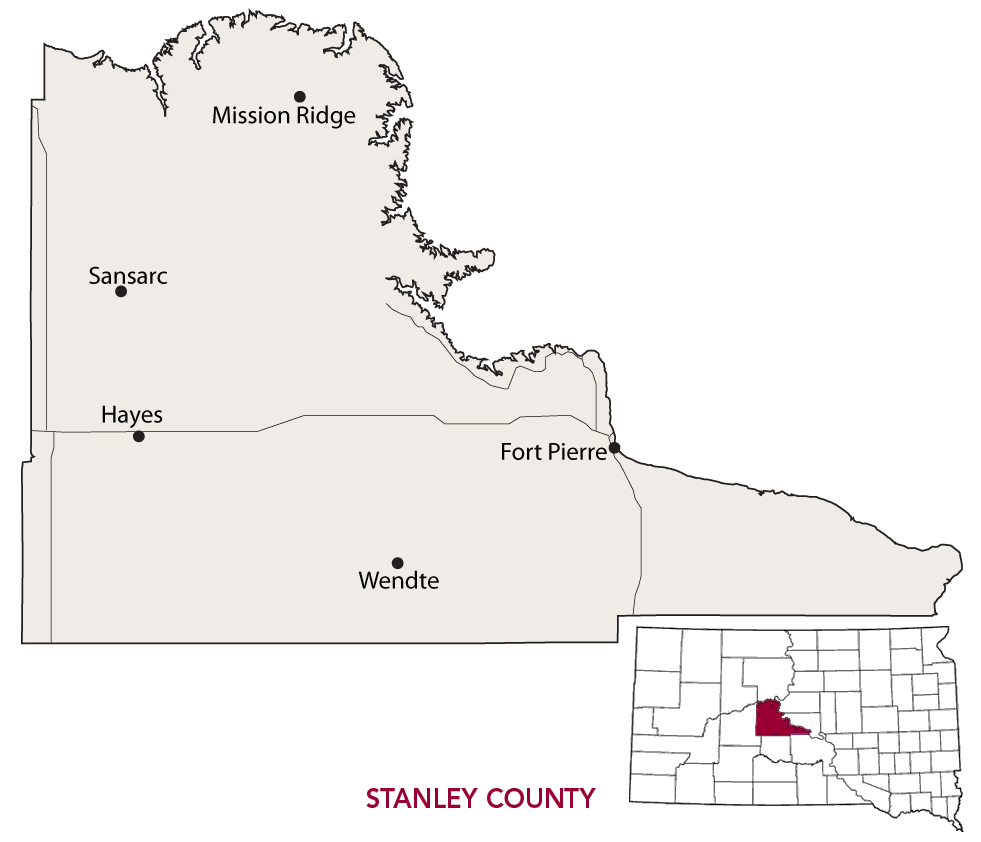

In 1743, French brothers Louis-Joseph and Francois La Verendrye buried a lead plate on a hill overlooking the Missouri River. They were among the first white men to ever lay eyes on the land that became Stanley County. The area has been the site important moments in South Dakota history: a clash of cultures, the resurrection of our national mammal, the birth of a rodeo legend, the filming of an internationally acclaimed movie — and the rediscovery of that historic plate left nearly 275 years ago.

The Verendryes had embarked upon an expedition to discover a vast Western sea. When they reached the bluffs of the Missouri, they claimed the land for France by burying a plate. It lay hidden until the day in February 1913 when Ethel Roberts, Harriet “Hattie” Fister and George O’Reilly went out to play.

“It was a Sunday and it was nice and warm, just a little snow,” Roberts told us in 1989. “Hattie happened to notice something sticking out of the ground. She kicked it with her toe but it wouldn’t budge.”

|

| Ethel Roberts with the Verendrye Plate in 1989. She was one of three children who found the plate in a Missouri River hillside in 1913. |

Finally, they pried it out of the ground. “George scraped off the gumbo with his knife and we saw the writing on it. If we had studied our history, we should probably have known what it was. But we just threw it down and went on playing.”

They agreed that George would try to sell the plate for scrap, but on his way home he ran into two state legislators. After recounting his experience, they notified state historian Doane Robinson, who had studied and written extensively about the Verendrye Expedition. He knew immediately that the children had discovered an artifact that proved European exploration of present-day South Dakota much earlier than previously thought. The plate now resides in the Cultural Heritage Center across the river in Pierre, and a monument marks the site of its discovery.

By the time the kids unearthed the plate, the town of Fort Pierre had grown from a remote fur-trading outpost to the seat of Stanley County. The Missouri River fur trade began to gain momentum in the late 1700s, and by 1830 the area around Fort Pierre was a bustling trade center. Fort Pierre Chouteau, named for the St. Louis fur trader, was established in 1832.

By 1855 it had become a military post to serve as a transportation and supply hub for travelers heading west into the Black Hills. That same year, Lieutenant G.K. Warren transformed an old Indian trail heading west from Fort Pierre into a bona fide roadway for Gen. William Harney to use during his fall expedition into the Black Hills. After gold was discovered in 1874 prospectors rushed to the Hills, often along that very same 220-mile Fort Pierre to Deadwood Trail. It became the primary route to the Black Hills until railroads and other modern forms of transportation overtook wagons. In 2008, local historians used GPS devices to map the original trail and staged a 17-day commemorative wagon train.

|

| Fort Pierre's annual Fourth of July rodeo dates to 1822. |

A lot of livestock trod across Stanley County during that ride, but that’s not unusual for a county rooted in ranching and rodeo. The annual Fort Pierre Rodeo, held on the Fourth of July, is said to be the oldest rodeo in the state. The event dates to 1822, when it was simply a series of horse-handling events between Indians and fur traders held at the confluence of the Bad and Missouri rivers that became a tradition during an annual rendezvous. It’s held at the Casey Tibbs Rodeo Arena, named for the six-time PRCA saddle-bronc champion who was born in a cabin along the Cheyenne River about 50 miles northwest of Fort Pierre.

Tibbs entered an amateur rodeo at age 14 and won four first place awards. He turned pro as a teenager, and in 1949 — at age 19 — he became the youngest man ever to win the national saddle bronc-riding crown. Between 1949 and 1955, he won a total of six PRCA saddle bronc-riding championships, a record still unchallenged.

|

| A virtual bronc at the Casey Tibbs Rodeo Center in Fort Pierre simulates an 8-second ride. |

When he died in 1989, Tibbs agreed to give many of his mementoes to his hometown. Today they are housed at the Casey Tibbs Rodeo Center, which opened in Fort Pierre in 2009. The facility also includes an exhibit to trick rider Mattie Goff Newcombe, a cowgirl from Faith who performed dangerous stunts on horseback in the 1920s. There’s a sculpture garden honoring South Dakota’s best saddle bronc riders and a virtual reality bronc that simulates an 8-second ride.

Stanley County has also been where the buffalo roam, thanks to ranchers Fred Dupree and Scotty Philip. In 1883, bison numbers had grown startlingly small. Hoping to help stave off extinction, Dupree captured five bison calves and brought them to his ranch. After his death in 1898, Scotty Philip bought Dupree’s herd and moved them to his ranch near Fort Pierre. The species rebounded splendidly. Travelers can watch huge herds grazing the prairie along the Bad River Road, a 50-mile stretch of mostly gravel that runs across Stanley County from Fort Pierre to the junction with Highway 83 north of Midland. The road passes through media mogul Ted Turner’s Bad River Ranch, which encompasses 141,000 acres that support the largest privately held bison herd in the country.

The world got a chance to see Stanley County on the big screen in 1990, with the release of Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves. Much of the filming was done on Roy Houck’s Triple U Buffalo Ranch, northwest of Fort Pierre. In 2015 the ranch was sold to Turner.

|

| Fort Pierre historians (from left) Darby Nutter, John Duffy and Gary Grittner help maintain the Verendrye Museum, a shrine to pioneer cowboys. |

Stanley County itself dates to 1873, just before it became a busy hub for travel further west. The county was named for David S. Stanley, commander at Fort Sully, a military outpost that had originally been built in 1863 about 4 miles below present day Pierre on the east bank of the Missouri. Its main task was to protect settlers from Indians. When Stanley took command in 1866, the fort was abandoned due to its low and wet location along the river. Stanley moved the fort 23 miles northwest along the river and became home to the 22nd U.S. Infantry from 1866 to 1873.

During his time at Fort Sully, Stanley grew to respect the local Indian tribes, working with missionaries like Father Pierre Jean De Smet to gain their trust and actively working to achieve peace between them and the U.S. government. Stanley served at Fort Sully until 1874, and the fort itself was finally abandoned in 1894.

Relations between Natives and non-Natives in Stanley County got off to a rocky start. During their exploration of the Missouri River, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had a tense meeting with the Teton Sioux at the confluence of the Bad and Missouri rivers. For four days, the two sides teetered between war and peace.

Communication was the main impediment. They could only speak through rudimentary sign language and the limited knowledge of Pierre Cruzatte, a member of the expedition who understood the Omaha language, but very little Lakota. On their first day there, the two sides exchanged gifts, as was customary, but then things went awry. One of the head tribal men drank half a glass of whiskey and nearly started a fight with Clark. When Clark and a few other men reached shore in a pirogue, several Indians grabbed its mooring cable and refused to let them return to their keelboat.

|

| The frames of seven tipis stand on the grounds of the Wakpa Sica Reconciliation Center, a project meant to build bridges between Natives and non-Natives but was stymied after the loss of federal funding. |

Lewis ordered in armed American reinforcements, while Indians lined the shore with bows and arrows. But tensions eased, and the next day the two sides enjoyed a great feast. The roller coaster continued until Lewis and Clark left.

The language barrier was a major obstacle, but had the explorers brought Pierre Dorion it’s possible much of the tension could have been eased. They met Dorion, a fur trader who had spent years living in the area and was fluent in the local Native language, when the party passed present-day Yankton. But instead of adding him to their crew, they dispatched him to Washington, D.C., to present a report on the area to President Thomas Jefferson. Clark lamented Dorion’s absence in his journal entry for Sept. 25, 1804. “We feel much at loss for the want of an interpreter,” he wrote. “The one we have can Speek but little.”

There have been ups and downs ever since, but perhaps hope lies within the Wakpa Sica Reconciliation Center. Established in 2000, the center is meant to improve relations between Natives and non-Natives, set up an intertribal justice system and create economic development opportunities. The campus includes seven tall tipis constructed on the prairie north of Fort Pierre, each representing one of the seven Teton Sioux bands, or council fires. But unfortunately that is as far as the project has gone. Federal funding withered several years ago and development at Wakpa Sica stalled, but tribes have shown interest in reviving the idea. Even though two French brothers once claimed this place belonged to the French, it might help show that Stanley County can be a welcoming home for everyone.

Editor’s Note: This is the 24th installment in an ongoing series featuring South Dakota’s 66 counties. Click here for previous articles.

Comments

across Stanley County from Fort Pierre to the junction with Highway 83 north of Midland

Very cool photos, writing, and an important history lesson. Great job.