The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

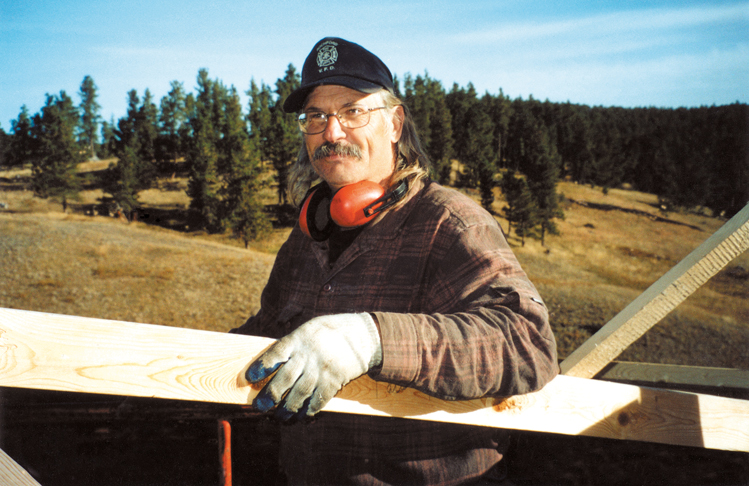

Terry’s Domain

|

| Terry Hill builds domes where his clients live, from wide open pastures to tree-encircled homesteads. |

During the Vietnam War, Terry Hill made himself a promise. If he got home, he would do for the rest of his life what he could enjoy. He’s kept that promise.

That doesn’t mean just sitting by the fire with a guitar in his hands, or building boats and floating the Missouri River, though those are among his favorite things. It means that the work he puts his hands to will be creative work, work without a boss, work in which he can take pride.

In Clay County, where he lives when a job or other fun doesn’t take him elsewhere, many have seen an unglamorous room of their home transformed by Terry’s hands. But it is for something more unique that he is known. He is South Dakota’s foremost builder of one-of-a-kind domes.

But don’t call him up and order a new dome for occupation in the spring. Terry isn’t about to hire a crew and advertise for jobs. He works alone most of the time, works his own hours — which may be well over eight — and has other priorities than finishing by a certain date.

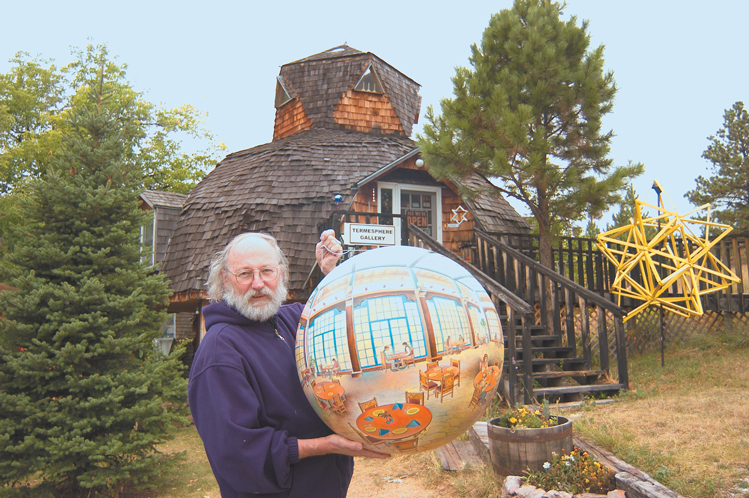

The seed of dome building took root in Terry’s mind when he was a student of Dick Termes, the famed creator of Termespheres in Spearfish. If you’ve been to Deadwood’s Saloon No. 10, you’ve seen a spherical double of the historic establishment’s interior rotating above the bar. Termes’ sphere that encapsulates in one continuous scene Lewis and Clark’s voyage up the Missouri hangs in the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre.

But back to Terry Hill. Two things happened when he was a student at Black Hills State University in the early 1970s. Termes and others brought famed engineer and building designer Buckminster Fuller, the father of the geodesic dome, to Spearfish.

|

| Terry Hill has built dozens of homes, ranging from relatively temporary and primitive structures to large, elaborate homes. |

Terry had seen pictures of Fuller’s grandest dome, the United States pavilion at the 1967 Montreal Exhibition. Now he heard Fuller speak, and wandered through the dome that had been temporarily erected on campus. Terry would never be the same.

Then Termes decided to move inside a sphere. He asked Terry to build him a dome.

South Dakota’s most famous dome, USD’s Dakota Dome in Vermillion, is visible from the window of the dome where Terry lives. Terry has a personal connection to the sports arena. In 2001, steel replaced the Dakota Dome’s synthetic fabric roof that had kept football and basketball players dry for over 20 years — except for its second year, when the roof ripped under a load of snow. The fabric was repaired, but many yards of good material was up for grabs, and Terry got a share. He still takes inspiration from floating the Missouri River in the canoe he built and covered with a scrap of Dakota Dome roof.

But from an engineering standpoint, the Dakota Dome is a simple structure compared to Terry’s dome. It’s an icosahedron. Of the many domed homes Terry has built, no two are alike. What would be the fun in repeating a creative act when other challenges lay ahead? But an icosahedron?

“It’s one of the Platonic solids,” Terry explains, “one of the five three-dimensional shapes that have the same angles on all the faces.” He launches into an explanation of variations of the dome, but soon it is apparent that it would be simpler just to build one than try to make me understand. Tetrahedrons, four sides with equilateral triangles, I comprehend, since that sounds something like the more conventional house in which I live. But trying to visualize dodecahedrons, which have 12 sides and every face a pentagon, is another thing.

Terry tries again: “An icosahedron is a 20-sided Platonic solid, one of the natural forms Plato described 2,400 years ago. Lots of life forms, like crystals, are Platonic solids.” The bottom five facets of Terry’s house are missing, of course, replaced by a flat floor. So the walls and roof of his house consist of a mere 15 equal triangular sides.

Yankton native Ed Johnson and his wife, Michelle Martin and their family live in another Clay County dome that Terry built. They were living in Pocatello, Idaho, where Ed worked as a psychiatric nurse, when they saw the chance to move home to South Dakota. “Actually this was 25 years in the works,” Ed said as we lounged in the late afternoon light on his front steps. “When we lived in Pocatello, Terry came out and built a domed sauna for us. Johnny Dome Seed. I was always going to move back, and I knew that when I did, I wanted Terry to build a dome.”

We go inside for a look. This dome is larger than Terry’s, 40 feet in diameter. I marvel at the construction, but still struggle to visualize how such a house is put together. “Here,” Terry says, “I’ll show you.” He digs in his wallet for a well-worn card with three sets of numbers: A: .3486-10%; B: .4035-12%; C: .4124-12%.

|

| The skeletal frame of one of Hill's creations. |

“So that’s all you need to know to build a dome,” says Ed, for whom Terry also built smaller domes for a guesthouse and a sauna. His roaring laugh tells me I’m not the only one in the dark. “I’m good at carrying things,” Ed adds.

“This is for a three-frequency dome,” Terry continues, as if he’s mixing so many eggs with so much milk and flour to make a cake. “There are three struts. This number times the radius in inches will give you the length. The 10 percent is the angle of the bevel at the end of the strut.”

Terry sees that conveying abstractions is hopeless, and like a good teacher, he resorts to show and tell. We step inside Plum Lodge, Ed and Michelle’s guesthouse. The interior of this 24-foot dome is unfinished, which makes construction techniques easier to grasp. In the open space I realize two other marvels of domes: They seem much larger inside than out, and they amplify our voices; we unconsciously adjust them down.

To talk about domes requires setting aside conventional assumptions about buildings, concepts like walls and roof. It’s like asking where a snake’s neck ends and its tail begins. Terry explains that “geodesic” means the shortest line between two points, and that a dome is built by connecting many points to form the many facets of the surface. I observe that every facet in this dome has either five or six sides — pentagons and hexagons — but even with evidence before my eyes, I’m glad I won’t be tested on the information that A struts radiate from the centers of pentagons, B struts are their border, and C struts radiate from the centers of hexagons. I did build my own house, but my mind takes refuge in straight walls, where the ideal corner is 90 degrees. My eyes glaze over and Terry gives it up with a laugh.

Talk about job security. Everybody admires Terry’s work, but few will take the challenge. “But I’m not advertising,” he reminds me. “I’m not looking for work.”

Both Terry and Ed are artists and musicians, and both speak of the calming feeling they gain from living in homes without corners or straight walls. “I don’t really think about it,” Ed says, “but I feel it. I had a good feeling when I first stepped into Dick Termes’ dome a quarter century ago, and I’d wanted one ever since.”

Ed speaks of the naturalness of round structures, the sacredness of the form in Native American cultures, which he thinks grew from reverence for the dome of the Earth. And in fact, Terry’s domes are far from the first in South Dakota. Centuries ago the Arikara lived in domed earth lodges along the Missouri, and Native dwellings from Lakota tipis to Inuit igloos to Navajo hogans are round.

In the more than three decades since he strolled through Buckminster Fuller’s dome, Terry Hill has built and lived in several of his own, once wintering in a dome that consisted of a parachute stretched over a lath frame. “It served well, actually,” he said. Most of his domes are far more substantial; he has built them as far away as Alaska, but most are in South Dakota.

In the winter of 1976, Terry, his wife and their newborn daughter were living in a primitive cabin near Custer. “There was a dome book in the cabin, which I was reading, and there were a bunch of little dead trees on the property, so I cut them down and made a little dome for a sauna,” he recalled. “That gave me the idea that I could actually build a dome to live in, so the next year I built a dome on my mother-in-law’s land west of Custer, and we lived there a couple of years.” Later, when Terry worked as a logger near Rochford, he lived in a primitive 12-foot dome he built near his work site, which he said was more comfortable than the winter he spent in a tipi near Deerfield Lake.

Word of Terry’s domes spread. Dick Termes called his former student and asked if he would build a domed studio next to his dome home near Spearfish. Another friend asked Terry to frame a dome for him near Nemo. He built one at Little Eagle on the Standing Rock Reservation, where in the absence of electricity he used a chain saw to frame the structure. The next he built near Fairbanks, Alaska.

In 2002, he began a large dome near Rochford, for Lucy Gange, an Eagle Butte native who is a professor at the University of North Dakota, but considers the Hills her home. The pair designed the house together, and each summer they built another phase. “Terry is the builder,” Lucy said. “I hold the dumb end.”

|

| Hill built one of his signature domes for Spearfish artist Dick Termes, creator of the Termesphere. |

This is the tallest dome Terry has built, four levels from the into-the-hillside ground floor to main floor to loft to reading cupola on top. Light filters through kaleidoscopic triangular stained glass windows, custom made by Carol Ellison of Rapid City. A pitch pine tree stands in the middle, now at the second level with lots of room to grow. “One thing I like about Terry is that he’s willing to incorporate what’s important to me,” Lucy said.

In an era when big crews frame a conventional house in a week, building a dome — especially the way Terry Hill builds them — is a different story. When Ed and Michelle decided to build, they found a long-abandoned farmhouse in a thick grove of trees in Clay County. Ed and Michelle were both working fulltime, so Terry mostly worked alone. But before construction on the 28-foot-tall dome could begin, Terry needed lumber.

Instead of calling the lumberyard, Terry disassembled the old farmhouse, a fine home that, judging by the inscription he found on a structural board, was built by Peter and Edwin Hesla in 1913, but was uninhabited for 50 years. Terry also tore down a deteriorating barn, and even salvaged lumber from the farmhouse where he grew up south of Wessington. “It was a little farm with cows and pigs and chickens, the kind that doesn’t exist now,” Terry said. “My folks moved to town, and the new owner was going to burn the house down. I said, ‘Gee, I’d like some of that lumber.’ So my old house lives on.”

“There’s even a sink in here from Terry’s family’s house,” Ed said. “And when we were building, we’d look up and there was a section of different-colored wood, like a patchwork quilt, and Terry would say, ‘Yeah that piece came from so and so.’”

Ed and Michelle’s 40-foot dome sits on a 32-foot, round concrete basement wall; the floor of the dome is cantilevered 4 feet out, giving the dome the appearance of a giant mushroom. Ed and his family moved in when the shell was finished, and the interior work continues. But in the meantime Terry built them a barn, a greenhouse and two more domes — the guesthouse, which Michelle dubbed Plum Lodge for the plum grove by which it stands, and a 12-foot sauna, also of recycled wood.

Most people these days are in too big a hurry to fool with recycling lumber. Once an old building is torn down, there are nails to pull. Some pieces will be damaged, so the lumber will not be uniform. But Terry prefers building with recycled wood. He’s not in a hurry, he likes reusing what would otherwise be burned or thrown away, and the quality of 50-year-old boards is generally superior to what is available today. “Plus I buzzed off about a hundred thousand logs in my lumbering days in the Black Hills,” he said. “I’ve got to atone for that.”

“Is there a downside to domes?” I asked.

“It’s definitely more work,” Terry said. “There are lots of angles. You can build a cube much faster.”

And besides not having big flat walls to hang oversized art on, are there drawbacks to living in a dome?

“I can’t think of anything,” Ed said. “I can even get my exercise in winter, power walking around the perimeter.”

Terry conceded that while domes are easy to heat, they’re harder to cool than conventional homes if exposed to the sun, because they have lots of surface to heat up and no attic to vent heat away. But Ed and Michelle avoided that problem by building amidst big ash trees that surrounded the old farmhouse their dome replaced.

Between domes, Terry still does conventional building and remodeling, but he’s happiest when conceiving and building a dome. He loves the beauty, the strength and the feel of the form, but he also likes knowing that for the material used, no other structure provides as much uplifting living space.

One other potential problem though. Without corners, where do spiders hang out?

“Don’t worry,” Ed said. “They find a place.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2004 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

I was a student at USD and remember well driving across the state to see Buckminster Fuller speak for an hour at Black Hills State. His books really inspired me.

Sending my best wishes to you guys - - - anybody knows where Dale is?

Ron Ringsrud

Saratoga CA ron@emeraldmine.com

www.emeraldmine.com