The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Ironman Governor

Editor’s Note: Former South Dakota Governor Frank Farrar died on Oct. 31 at age 92. We visited him in his Britton office during the summer of 2018 for this story, which appeared in our May/June 2019 issue.

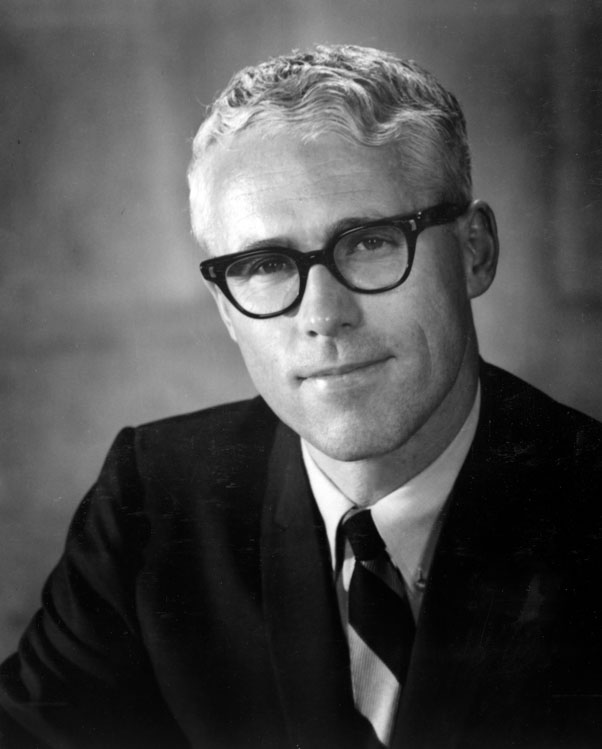

Just a few black and white pictures hang on the walls of Frank Farrar’s office. They are nearly the only reminders that a visitor finds of Farrar’s political career, which included six years as attorney general and a single, two-year term as governor of South Dakota. Politics was just one chapter of Farrar’s life — a chapter that ended nearly 50 years ago.

|

| Frank Farrar, a lawyer from Britton, was South Dakota's attorney general from 1962 to 1968 and governor from 1968 to 1970. |

Instead, when you walk in the door of First Savings Bank on Main Street in Britton, head to the back and hang a couple of rights, you’ll find Farrar at his desk, focused deeply on the paperwork before him and surrounded by dozens of medals, plaques, posters and certificates commemorating his athletic prowess. The former lawyer, attorney general, governor, banker and businessman has completed 36 Ironman endurance races. That’s a 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bicycle ride, and a full marathon. He’s also completed several triathlons and other smaller races — all since turning 65 and on a leg held together with nails. “I’m not much of an athlete,” he says, with a slight grin. “More of a plug horse.”

At age 90, he’s still active as chairman of Performance Bankers, Inc., which oversees banks in several states. Dozens of banker’s boxes stacked in the hallway outside his office serve as proof. It’s a career he launched in the wake of a financial crash in the 1980s. Farrar bought struggling savings and loan institutions in small towns, rehabilitated the balance sheets and then sold them back to members of the community. He’s bought and sold banks from New Mexico to Montana to Indiana. “But I’m not a banker,” he says with a wave of his hand. “I just have outstanding people working for me.”

What of his career in law and politics? Nearly three generations ago, the lawyer from Britton launched a successful campaign for attorney general of South Dakota, and after three terms was elected governor in 1968. “I wasn’t much of an attorney general,” he says, almost predictably at this point in our conversation. “I had outstanding assistants. When I had a really difficult case, I picked the best lawyer in South Dakota, put them on the payroll and had them try the case. And we never lost.”

If there were a gold medal for modesty, you might find that on Frank Farrar’s wall, too — or tucked into the back of a desk drawer, more likely.

***

The Britton into which Farrar was born on April 2, 1929 was home to about 1,300 people. The Marshall County seat, tucked into the northern reaches of the Coteau des Prairies, has seen population fluctuations over the decades, but by and large Britton has withstood the outmigration that has preceded the demise of many other South Dakota small towns; around 1,250 people still live there today.

Main Street, running north and south through town, remains busy. The Marshall County Prayer Rock Museum anchors the corner of Highway 10 and Main Street; a mural by Adam Eikamp that honors the town’s history greets travelers entering Britton from the east. Jean Amacher and her daughter, Kelsi Heer, do brisk business at their boutique called Dizzy Blondz. Movies still screen at the historic Strand Theater; its bright red, white and blue façade stands out on the east side of Main among the surrounding brick buildings. The brick hospital in which Farrar was born still stands, though health care services have moved to the Marshall County Healthcare Center Avera on the southeast side of town. Farrar’s office inside First Savings Bank is across the street at the end of the block.

|

| The Farrar family, which included (from left) Sally, Jeanne, Pat, Anne, Frank, Robert and Mary, moved into the governor's mansion in Pierre in early 1969. |

Many South Dakotans are descended from homesteaders who emigrated from Europe in the 19th century, but Farrar can trace his maternal ancestry to George Soule, who crossed the Atlantic as an indentured servant on the Mayflower in 1620, signed the Mayflower Compact and helped establish Plymouth Colony. Shortly after he was elected governor in 1968, the Soule family historian documented Farrar’s lineage and included it in the 70-page newsletter sent to family members around the world.

Legend says another Farrar ancestor had a run-in with Abraham Lincoln, when the future president was piloting boats along the Mississippi River. “Our family was involved in boating, and they didn’t think this guy would amount to anything,” Farrar recalls with a chuckle. “They got into a fight over a girl and Abraham Lincoln threw a solid ear of corn at him. He was scarred for life.”

Eventually, Farrar’s parents — Virgil and Venetia Farrar — found their way to a homestead near Newark, a long-forgotten village 9 miles north of Britton and just a half-mile from the North Dakota border. Farrar attended school in Britton, where he became an Eagle Scout, was elected student body president and played football, which had life-long consequences.

During a game in about 1946, Farrar took an awkward hit to his left knee. A knee replacement procedure would have been the perfect fix, but such an operation didn’t exist 70 years ago. Instead, doctors at Mayo Clinic gave him two options: amputation at the knee or plastic cartilage nailed into the bone. “I said, ‘I’ll take the nails.’ My mother didn’t raise any smart children, but I was smarter than that.” The nails are still there, even after a left knee replacement in 2017. “They’re not hurting anything,” he says, nonchalantly.

Farrar dreamt of becoming an engineer, so he applied to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City. The school replied with an aptitude test, which Farrar completed and returned. “They sent a note back,” he recalls. “‘We sure appreciate your interest in our school, but you’re in the lower percentile and we don’t think you should be engineer.’ So I went to the university.”

That was the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, where he studied law and was again elected president of the student body and of his fraternity. He graduated in 1951, and two years later he married Patricia Henley, a farm girl from Claremont. The Farrars raised five children and remained close partners in life until Pat’s death in 2015.

With a law degree in hand, Farrar set out to find work, but prospects were slim. “That put me on the map to do something,” he says of his success at USD. “But when I got out of school I tried to get a job, and nobody would hire me as a lawyer.”

Farrar’s parents were living in the state of Washington at the time, so he and Pat moved west in 1955. Farrar took a job with the Internal Revenue Service as a state gift tax examiner. When Pat’s father was diagnosed with cancer, the couple moved back to South Dakota. Farrar was elected Marshall County Judge in 1957 and state’s attorney in the fall of 1958.

***

Four years later, at age 33, Farrar became the youngest person in state history ever elected attorney general. He investigated abuses in the insurance industry, resulting in a complete rewrite of the state’s insurance laws. His dogged prosecution of corporate officers and his tough stance on drug and narcotics violations engendered a broad base of support, which translated into a successful bid for governor in 1968.

|

| The Governor and First Lady helped celebrate South Dakota's 80th birthday in November of 1969. |

It was a turbulent time to take the helm. Protests against the Vietnam War popped up throughout the country, including in South Dakota. Farrar and members of his administration were attending a national governors meeting in New Mexico when they received word that a riot had broken out back home. Farrar quickly returned, only to discover that he had a personal connection to the disturbance. “One of my staff members was in the riot, so I politely fired him. I said, ‘We don’t do riots.’”

Farrar hoped to avoid more unrest when the fate of Thomas White Hawk landed in his hands. White Hawk was an 18-year-old student at the University of South Dakota in 1967 when he murdered Vermillion jeweler James Yeado and raped Yeado’s wife.

White Hawk had been sentenced to death, but after becoming governor in 1969, Farrar commuted his sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Tensions were rising on South Dakota’s Indian reservations, and the American Indian Movement had been created during the summer of 1968. Farrar hoped the commutation would quell any further violence. “I wanted to give him the death penalty. I believe in the death sentence,” Farrar says. “But I got more than a thousand letters from Indians saying if you give this guy death you’re discriminating. I said to myself, ‘They think I’m prejudiced.’ So I gave him life without parole, with the addition that as long as I lived I’d go to the parole board to ensure they didn’t let him out. I kept my promise. He was there 30 years, and whenever the parole board met I’d send a note: Do not let him out. And he died in there in 1997. I did that for the Yeado family.”

Farrar met many of the same challenges that subsequent governors have faced, including funding for education, health and welfare programs (which made up 85 percent of his budget for the 1971 fiscal year). He also tried reorganizing the executive branch (which ultimately occurred in the mid-1970s after he left office), tax reform and a program to help settle disputes between rural electric cooperatives and privately held companies. Pundits thought that controversies surrounding these and other issues led to his defeat in 1970, a 55 percent to 45 percent contest against Democrat Richard Kneip, a wholesale dairy equipment salesman and state senator from Salem. But Farrar believes the reasons were much simpler. “One was the war and the other was the economy. It went down right during the time of the election,” he says. “Oil went from $3 to $30 a barrel. We went from 32 Republican governors to 21.”

Farrar left the state capitol in 1971 after a single, two-year term as governor and never again sought political office. He’s lived the longest (48 years) of any South Dakota governor after leaving office. But he still remains connected to state politics. Former attorney general Marty Jackley sought and received Farrar’s endorsement during the 2018 Republican gubernatorial primary. And as we sat in Farrar’s office on an unseasonably cool and cloudy August morning, his cell phone buzzed with an incoming call from Dusty Johnson, then campaigning for South Dakota’s lone seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. “He can wait,” Farrar said, and silenced the call (sorry, Dusty).

***

Farrar re-entered the private sector by resuming his law practice and eventually getting into banking. A financial crisis in the 1980s led to the demise of hundreds of small savings and loan institutions throughout the country. He founded Performance Bankers, Inc., and became adept at buying them, turning them around and then selling them back to members of the community. He also believes in financial education. “I sponsor and pay for a program to teach high school students how to take care of their money, what a FICO score is, what a credit card is, and how important it is to stay out of debt,” Farrar says. “It takes 6 to 10 years if you go bankrupt to get out again. Wherever I have banks I sponsor and pay for that program.”

|

| At age 65, Farrar began competing in triathlons and Ironman competitions, including the Scheels Dakotaman Triathlon at Lake Alvin in 2015. Photo by Jon Klemme. |

Perhaps the achievements that garner the most attention these days involve endurance races that he travels the globe in which to compete. Farrar has always believed in the importance of diet and exercise. As governor, he often swam across Lake Oahe. Occasionally, he could be found practicing with the Pierre Governors high school basketball team. One old black and white photo shows him and Pat and their children riding bicycles around the capital city. “If you properly exercise and have the right diet, you’ll live a longer life and a more comfortable life,” Farrar says. “But exercise really does not lose weight. Food loses weight. So our problem in America is food. But the beauty of exercise is that it’s great for people who have to be on medicine. There’s really no reason to take all these opioids that are killing people if you do those two things: exercise and eat properly.”

Farrar would have been a triathlete at an early age, but the races didn’t exist until the early 1970s. Still, in his early 60s, he got involved. Then he set his sights higher. “I was doing all of these little sprints, so I thought, ‘Why don’t I work myself up to an Ironman?’”

Since making that decision, he’s competed in 36 Ironman events, most recently the 2018 Grand Final on the Gold Coast of Australia. He’s been one of the very few competitors in the 85-89-year-old division. “If nobody shows up I win. If they do show up, then I’m last,” he says.

Farrar has also completed more than 380 triathlons, both sprint (750 meter swim, 20 kilometer bike ride and 5 kilometer run) and Olympic (1.5 kilometer swim, 40 kilometer bike ride and 10 kilometer run) distances. He attributes the vigorous exercise to saving his life several decades ago.

In 1973, Farrar was in a business meeting in Pierre when he felt a lump on his neck. Doctors at Mayo Clinic diagnosed him with non-Hodgkins lymphoma and told him he had two months to live. “I said, ‘What are you talking about? I don’t even hurt.’ But he said, ‘At your age, and based on what we know, you’ve got two months. We’ll give you chemo.’ I was doing triathlons and kept doing them. I took chemo and kept swimming and in six months I was in remission. The doctors were amazed. I attribute it to exercise and attitude.”

***

|

| Farrar was surrounded by athletic medals and plaques in his Britton office. |

Life in Britton these days is exciting, yet simple for Farrar. “I get up, I work out, go swimming. I work all the time, every day including Saturday and Sunday.”

A few days after we left Britton, the town unveiled a historic marker commemorating the 50th anniversary of Farrar’s inauguration, although he didn’t mention it during a 90-minute interview. Jean Amacher told us about it later at Dizzy Blondz.

The town was also preparing for Harvest Days, Britton’s annual summer celebration, and Farrar expected that many of his five children and nine grandchildren might soon arrive for the festivities. “They’ll probably all come roaring in here because it’s a fun time,” he said.

Farrar envisions many more Harvest Days, triathlons and Ironmans in his future. “You can control your life, and life is beautiful,” he says. “I want to live forever. I don’t want to die. I put in my will, ‘If I ever die…’”

Frank Farrar turned 90 on April 2. If you ask, he’d probably say that he will be a poor nonagenarian. Let’s hope he’s right.

Editor's Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2019 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments