The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Lost 74

|

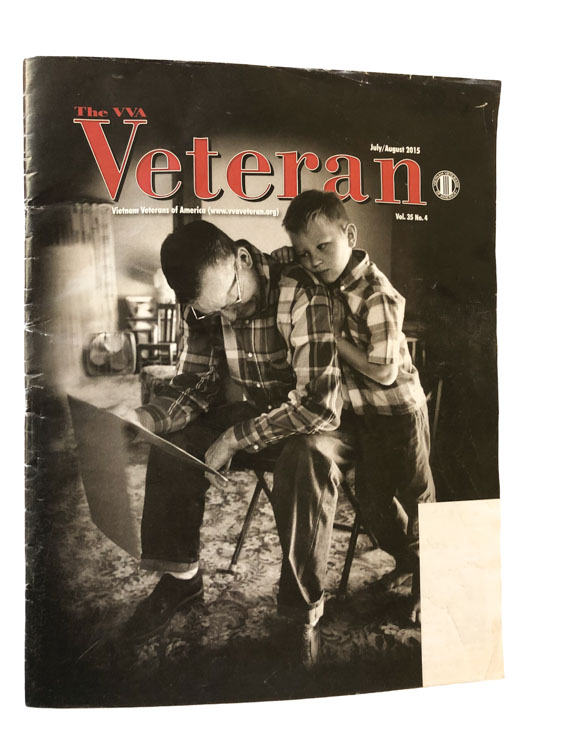

| The Sage brothers (from left, Gary, Kelly Jo and Greg) posed for this photograph as a Mother's Day gift before they left port in California for the waters off Vietnam. |

There are worse things than being forgotten. Maybe you’re halfway around the world, in the dark of night on the South China Sea, when your ship collides with a much larger vessel.

Maybe you’re a sailor on a nearby boat that attempts to rescue survivors, but all you see is endless water and an eerie quiet.

Maybe you’re a Nebraska farmer listening to the TV news when you hear that the ship on which your three Navy sons are serving has been sliced in half.

Maybe you’re a young wife and mother whose father-in-law telephones to say that your husband — his son — won’t be coming home. You get a telegram from the Navy confirming the news.

A week later, the final note of “Taps” has faded to silence. The burial flags are folded and put away and the sympathy cards have been read and answered; then a lonesomeness settles over great tragedies.

That’s when the survivors contemplate the grace of remembering.

***

Brookings barber Linda Vaa was the young sailor’s wife who got that phone call from her father-in-law in 1969 at the height of the Vietnam War. Fifty years have barely softened the pain.

|

| Linda Vaa, a longtime barber on Brookings' Main Street, strives to preserve the stories of 74 sailors who died in 1969. |

She met Greg Sage in the summer of 1964 at the Knox County Fair in Bloomfield, Nebraska, just across the border from Yankton and Bon Homme counties in South Dakota. “My sister and I were walking around the fair when she noticed these two boys were following us. It was the day before school started. Finally, we turned around and started talking to them.” One was Greg Sage, a farm boy from nearby Niobrara. “Greg was very shy,” she says. “We probably dated three months before he held my hand. We were just 17 years old.”

Greg was the second of Ernie and Eunice Sage’s four sons. Gary, the oldest, was a typical first-born: serious and eager to help people. He was also a thinker who liked to read. As the United States became more engaged in Vietnam’s civil war, he told his family that he felt he should fight for his country.

Greg, who played football for Niobrara, was less studious than Gary. Kelly Jo, freckle-faced and artistic, was two years younger than Greg. The Sages’ fourth son, Douglas Dean, had barely started school. The boys and their father spent their days hunting, fishing and farming in the hill country of the Missouri River Valley.

***

Gary enlisted in the Navy after high school. Greg and Linda married as soon as they graduated from high school, and within a year Greg followed his older brother into the Navy. “Their dad, Ernie, encouraged them all to join the Navy because he thought it would be safer,” says Linda.

Kelly Jo signed up even before his high school graduation. Gary was on the crew of another ship when Greg was assigned to the USS Frank E. Evans, a 376-foot attack vessel commissioned in 1945 and deployed to the Pacific at the end of World War II. Sailors nicknamed it the Grey Ghost because of the way it looked at sea. The Evans was retooled in the 1960s for anti-submarine warfare. As fighting expanded in Southeast Asia, it began deployments there.

“Gary’s ship pulled into base at Long Beach, California, and he came to live with Greg and I for a while,” says Linda. “He taught me how to make a cherry pie. One day, Greg suggested that Gary transfer to the Evans so they could be together. About then, Kelly Jo graduated from high school and came to boot camp in San Diego. They asked him where he wanted to go, and he put down the Evans so he could be with his older brothers.”

Navy policies discourage family members from serving on the same ship, especially during wartime, but it is not expressly forbidden. In November of 1942, five brothers from Waterloo, Iowa, were serving on the USS Juneau when it was sunk by a torpedo in Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. More than 600 sailors died in that tragedy; there were at least 30 sets of brothers aboard.

The three Sage brothers boarded the Evans along with their fellow sailors in March of 1969 at the Port of Long Beach, headed for Vietnam. Gary was 22. Greg was 21. Kelly Jo was 19.

***

For weeks, the crew of the Evans used their firepower to protect American troops stationed on the Vietnamese coast. When they ran short of ammunition, the 2,200-ton ship was sent to the Philippines to restock before it left for training exercises with the Royal Australian Navy in the South China Sea.

At 3:15 a.m. on the morning of June 3, the Evans crossed paths with the much-larger HMAS Melbourne. Someone described it as a collision between a Volkswagen and an 18-wheeler. The Evans was cut in half. Greg and Kelly Jo were off duty and asleep in the lower berths in the bow. There were reports that their older brother, Gary, was on duty on the stern, which stayed afloat.

|

| The USS Frank E. Evans was a 376-foot attack vessel commissioned in 1945. |

“Nobody knows for certain what happened because it was total chaos in the black of night,” says Linda. “But it seems likely that Greg was crushed, because he was probably right where the ship was hit. What we’ve heard is that Gary jumped to the bow to try to find Kelly Jo.

“Gary had a flashlight, and we’ve heard that he went to the top story. There was a ladder blocking a door there and some officers were trapped inside. A dozen people were trying to get the officers out. Gary gave them the flashlight and then left, we think, to go below to look for Kelly Jo.”

Some of the 204 survivors on the stern and witnesses on nearby ships reported seeing arms reaching out from the windows and hearing screams as the bow laid to one side and then, within just three or four terrifying minutes, sank into the dark sea with 74 men trapped inside.

“That is what haunts so many of the men,” says Linda. “One sailor told me he came off duty when Greg went on duty that night. He took a shower and put on a pair of my husband’s underwear because his were at the laundry. He felt the collision, was thrown around and crawled out from under a mattress. He got to the ladder, but the hatch flew closed. Then, someone who had already got off came back and opened the hatch. At last it was his turn to climb off. He thinks he might have been the last one off. He jumped or was thrown into the water and he swam and swam until he found something to hang onto. A small ship came to save him but he told them he was OK and they should go save someone else.

“Those are the stories we hear,” Linda says. “They still hear the ghosts of the sailors who died.”

***

Ernie Sage finished working the fields of his Niobrara farm on June 3 and went to the house to watch the evening news on CBS when Walter Cronkite reported that the USS Evans had been cut in half. Ernie screamed and his wife, Eunice, passed out.

As soon as he was able, Ernie called Linda, his daughter-in-law, who was living in Omaha with her 13-month-old son, Greg Jr.

A week later, the family held a private service in the Niobrara Lutheran Church, and then they joined the entire community at the school for a military funeral that was televised. Officers folded four burial flags; they gave three to Eunice, in remembrance of her three sons, and one to Linda. A photographer from Life came to document the terrible grief but the magazine never used the pictures; an editor told the family later that it was just too sad for words or pictures.

Ernie, the father, was quiet and crestfallen. “He was never the same,” Linda says. “I think he felt tremendous guilt because he had encouraged them to join the Navy, but it was only because he thought it was safer. He became sad and depressed, so sad that he forgot he had another son at home.”

|

| Doug Sage, 6, the surviving brother, comforted his father in 1969. The family's grief attracted much media attention. |

The elder Sage spent a week at a state mental hospital, and then returned to his wife and son but he never smiled again — not until minutes before he died in a hospital bed at age 79.

Doug was 6 when his brothers died. “Ernie protected him and wouldn’t even let him drive a tractor or do anything where he might be hurt,” Linda remembers. “He didn’t get to grow up in the carefree way his brothers did, and he had to do naughty things to get his father’s attention.”

Linda says it was hard to return to a normal life. Sympathy letters poured into Niobrara from around the country. News reporters came to write about the little farm town that had sacrificed so much for a war that was growing more unpopular with every passing day.

She also noticed that her own toddler, Greg Jr., was being affected. Well-meaning townspeople spoiled him at every opportunity.

Three years after the crash, she and her son moved 120 miles north to Sioux Falls, where she was able to use her late husband’s GI benefits to attend beauty school and barber school.

In 1974, she was cutting hair at the Grange Avenue Barber Shop in Sioux Falls when Spencer Vaa, a Vietnam veteran who was injured in 1969, walked in and sat in the chair for a trim. They married two years later, and adopted a daughter, Sarah Jane, in 1982.

Spencer’s career with the S.D. Game, Fish & Parks Department led them to Brookings in 1978, where Linda went to work for Brookings Barbers. There, they raised Greg Jr. and Sarah.

***

South Dakota and Nebraska are 7,000 miles from the South China Sea, but the pain of June 3, 1969, could not be healed by time or distance. “He missed his boys so badly, he could never be the same strong man he was before they were killed,” Linda says of Ernie Sage. However, the father found some solace when he heard about plans for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C.

“Their dream was to go to Washington and see the names of their boys on the wall,” says Linda, “so when I got a fundraising request for the project I wrote back and said we would help, and I asked for the list of names because I wanted to be sure they got everything right.”

When the list came in the mail, she saw that her husband and brothers-in-law — in fact, all 74 Evans casualties — had been omitted. The Department of Defense had determined that they died outside the war zone. “I had to go tell Ernie,” says Linda. “I would have rather taken a shot to the head than tell him. It was like he lost them all over again. He cried for hours.”

Doug also struggled after the tragedy. “He started out with a big family and then he lost three brothers, and in a way he lost his father,” Linda says. Today he lives in Colorado.

The three Sage sailors’ mother, Eunice, found comfort in her deep Christian faith. She regained her good sense of humor and became a source of strength to others. She was as surprised as anyone when she took on a role as comforter to hundreds of men who survived the nightmare at sea.

That began to happen in 1992, when survivors formed the USS Frank E. Evans Association and started to hold annual reunions. Ernie, who died in 1996, never attended the gatherings but Linda and her son, Greg Jr., began to accompany Eunice Sage.

“The first one I went to was in Niobrara for the 25th anniversary,” Linda says. “We met a bunch of the guys then, and I realized they were wonderful people and they really loved Eunice. When they met her, some broke down and cried and said, ‘We’re so sorry your sons are dead and I’m alive.’”

Linda says Eunice would hear none of that. “She shook her fingers at them and said, ‘Don’t ever tell me that again! You’re alive to tell me what happened.’”

Eunice became known as the mother of the association. The Navy veterans took up collections to help her with travel expenses. Every time she arrived, someone would politely suggest that she rest in her hotel room, and she would respond, “I want a cigarette. I want a drink. And I want my boys.” She often remarked that she lost three boys, “but gained a hundred.”

The gatherings taught Eunice and Linda the sadness of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “We could see that they all felt guilty — survivors’ guilt. Every year we would all go into a room together, maybe 50 or 100 people or more, and every one of the survivors would tell how they got out of the ship. Every one of them has a story and they are haunted by their memories. They remember the arms reaching out of the windows or the screams coming from men in the water. They can still hear the ship breaking apart. They hear the ghosts.”

She says they all tried to restart their lives, but many struggled with work and relationships. “Many have been divorced three or four times. You would think the reunion would just bring back their worst memories but instead it seems to help because we are the Frank E. Evans family. I hug everyone three or four times, and I hug their wives because I know how hard it is for them, too.”

She knows a veteran who was a radarman, like Greg. “He doesn’t normally like to be around people. He moved to the U.S./Canadian border to be alone,” she says. “He has tremendous guilt because he thinks he should have been able to save someone. But he does come to join us.”

The 2018 reunion was held in the Black Hills of South Dakota, at the Grand Gateway Hotel in Rapid City. Linda says a familiar theme arose there: Why aren’t the names of the 74 Evans sailors on the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C.? Are they to be forgotten?

***

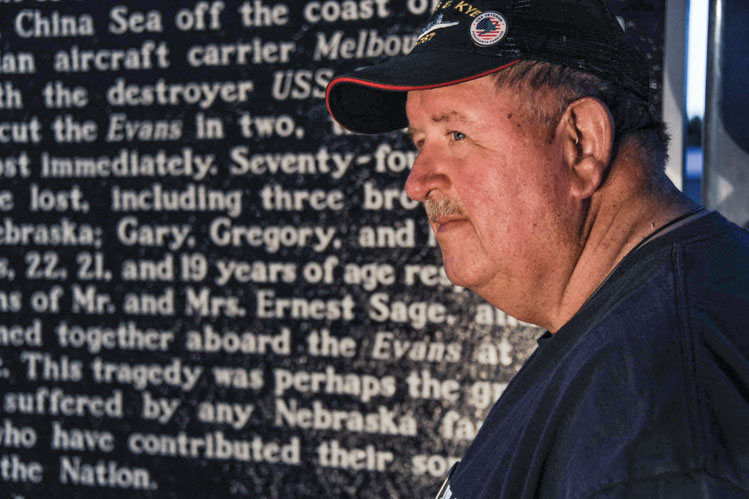

Darwin Sietsema leaves his home in Ruthton, Minnesota, every June and travels west into South Dakota. He visits a friend in Yankton, and then follows the Missouri River to Niobrara. After midnight on June 3, he parks his gray Chevy pickup at Farnik’s Market. He walks across the asphalt parking lot to a modest memorial with 74 names inscribed in stone. There he sits for several hours, in the quiet and darkness, reflecting on what he calls, “The worst day of my life.”

|

| Darwin Sietsema was among many would-be rescuers who rushed to help the sailors on the USS Frank E. Evans. Now he makes an annual vigil to their memorial in Niobrara, Nebraska. |

Sietsema grew up in Trosky, Minnesota, where his father operated the grain elevator. At age 18, he joined the Navy to avoid being drafted into the U.S. Army. After basics in San Diego, he was trained as a boiler tender. “It was miserably hot in the boiler room, though, so I worked my way into being an electrician.”

In the summer of 1969, he was assigned to join the James E. Kyes, a World War II-era destroyer. He had three deployments to the South Pacific. “Basically, we went from Pearl Harbor to the Philippines to Vietnam and back to the Philippines to Japan and maybe back to Vietnam. Each deployment was six to nine months. Our job was to fire our 5-inch guns in support of the troops. We could fire a quarter mile off the beach and our shells could go 12 miles.” Sietsema says the North Vietnamese had shore guns that could have reached his ship but the Kyes was never fired upon.

The mission was similar to the Evans, and Sietsema says it’s entirely possible that he crossed paths with one or more of the Sage brothers while they were all living in California. However, it’s a certainty that he was nearby when they died.

“I was asleep lying in my rack,” he says of the fateful night. “I thought it was a dream. Then came the command, ‘Man the rail!’”

His ship hurried to the accident site, but they found nothing but the silence of the sea. “We didn’t even know, right away, what had happened. Then we heard rumors that there had been a collision. But the sea was as calm as glass. Right away we launched our motor whale boats.”

As daylight came, the sailors learned the sad news. “On the second day, about a half dozen ships gathered and we had a memorial service at sea. When they played “Taps” it seemed like a haunting echoing sound. I don’t know how it can echo when there’s nothing out there.”

Sietsema remembers that he and his crewmates felt helpless. “There was nothing you could do. It was over with,” he says. But it never really ended, not for him or hundreds of others who were survivors, would-be rescuers, friends and family.

***

As it became obvious that the Department of Defense was not going to add the names of the Evans sailors to the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, the townspeople of Niobrara — who had already created a historical marker to the Sage brothers in 1999 — decided to build a memorial to all 74 in 2016.

“We wanted to make sure their names were on a wall somewhere,” says Jim Scott, commander of the American Legion post. “There are still efforts to add the names to the wall in Washington. I don’t know if that will ever happen. But these men will not be forgotten here.”

|

| Residents of the small Nebraska town of Niobrara, which lies on the South Dakota border near Springfield, vow that they'll not allow the 74 sailors to be forgotten. |

He and others raised funds to construct a granite memorial with the names of all the sailors. Their pictures are nearby on a vinyl poster.

An observance of the 50th anniversary of the tragedy was held this year on June 2 at 3:15 p.m., the exact hour of the day when the Evans sank (there is a 12-hour time difference between Vietnam and the Central Daylight Time Zone in the United States).

Sietsema was there, along with many Sage relatives, community leaders and dozens of others from South Dakota and Nebraska. The burly Minnesota trucker spoke briefly about that horrible night on the South China Sea, and he lamented that the 74 young men are not remembered on the wall in Washington.

Martha Atkins, the town’s Lutheran pastor, offered a prayer. “On this day of remembering, we bring forth 74 souls who were lost in service on behalf of this country,” she said. “Lord, we call upon you to embrace those families, those comrades in arms and the many, many friends of those 74 courageous young men into your arms of healing, of comfort and into peace.”

***

Linda Vaa is now in her 45th year as a South Dakota barber, working at the shop on Brookings’ Main Street. She gives $8 haircuts to military veterans on the last Tuesday of every month.

She is a busy wife, mother and grandmother. She has also collected books, newspaper clippings and photographs related to the Evans, and she stays abreast of continuing efforts in Congress to add the 74 names to the wall.

Encouraging news came this summer when Kevin Cramer, a U.S. senator from North Dakota, introduced the USS Frank E. Evans Act to require that the names be added. Cramer noted that it’s “not unprecedented” to make changes on the Vietnam wall. He said duplicates, misspellings and omissions have been fixed through the years.

The Pentagon continues to oppose such efforts, maintaining its 50-year-old argument that the Evans sailors died too far from the Vietnam battlefields to be counted as war deaths. The government’s designated combat zone, drawn by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965, did not originally include Cambodia and Laos.

Linda blames President Richard Nixon. “He was losing favor with the country over the war in the summer of ’69,” she says, so there is a theory that he and his generals were looking for ways to lower the number of casualties. She says she’s appreciative of congressional efforts, but she admits to some cynicism after 50 years. “I think it’ll take a president’s attention to change what started so long ago.”

She commends politicians, organizations and veterans who have worked to keep the memories of the 74 alive. “We don’t want them forgotten,” she says. “Those boys will never grow old, they’ll never enjoy their families. ‘Lest We Forget’ is a motto of the military, and that’s the one thing we can still do for them.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 2019 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Thanks much for repeating it!