The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Road Less Traveled

|

| Motorists driving state Highway 20 see the steeple of St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church on the horizon for several miles before reaching Hoven. |

South Dakota Highway 20 passes through nearly two dozen East River towns between Minnesota and the Missouri River. Only four have more than 300 people. Motorists often choose U.S. Highway 12 through Aberdeen or U.S. Highway 212 through Watertown when traversing the state’s northeastern quarter, so Highway 20 has become less traveled. The route could be considered one of our most rural highways, and it’s worth exploring. We found 200 year old pianos, South Dakota’s only pressed flower artist, legends of a prankster Indian chief, Civil War history (Union and Confederate) and new businesses injecting life into small towns.

Minnesota to the Big Sioux

Our journey began in Grant County, where Minnesota Highway 40 becomes South Dakota 20. Between the state line and Watertown, the road weaves around rolling hills dotted with huge boulders that could only have been left by glaciers that scraped the earth thousands of years ago.

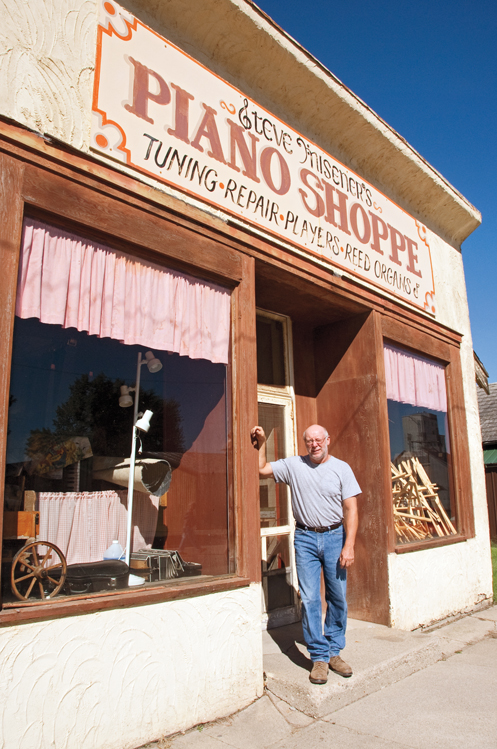

The first stop was Steve Misener’s piano shop on the Main Street of Stockholm, population 105. Misener began tuning and restoring pianos 30 years ago, and since then he’s become an avid piano collector and passionate music advocate. He has about 75 pianos and boxes stuffed with miscellaneous parts packed into his small shop, which was once the town grocery store.

|

| Steve Misener tunes, restores and collects antique pianos in his Main Street shop in Stockholm. |

His most prized pianos are two John Broadwood concert grands with connections to famous European composers (see sidebar). He also owns French and German pianos made in the mid-19th century and smaller square grands. One was made by Jonas Chickering in Boston in 1832, and may be the oldest privately owned Chickering. Misener knows of four others of that age in existence. They are at the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Henry Ford Museum in Michigan and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Misener jokes that he’s the first member of his family to pursue a career outside of agriculture in 100 generations. At age 13 he bought a player piano at an auction and became fascinated with its parts. After graduating from high school in Revillo, he attended technical school for piano tuning and repair. “I found out the ratio of pianos to piano tuners, and 35 years ago it was 5,000 to one,” he says. “There were 5,000 pianos out there with my name on them.”

The ratio may still be the same, but times have changed. “Seventy percent of the pianos in American homes today are furniture,” he says. “You set your family pictures on them and no one plays them.” He also read a study that found only 7 percent of Americans play an instrument. Those factors motivated Misener to revive interest in music by having students tour his shop and exhibiting a portion of his collection at Blue Cloud Abbey near Marvin last spring.

One morning 15 students enrolled in a music theory and history class visited his business. When he asked how many played an instrument, only three students raised their hands. “My generation has taught convenience,” he laments. “It’s much easier to spend 60 seconds and learn how to run an iPod than it is to spend six years and learn how to play the piano.”

Misener hopes to take his exhibition on the road to reach as many students as he can. He also welcomes tour groups. Call (605) 676-2355 to make sure he’s there.

In South Shore we met Tina Nielsen, owner of the South Shore Mercantile. Her business is the hub of activity in the town on the south shore of Punished Woman’s Lake. The Mercantile is a grocery store, hardware store, thrift shop, restaurant, video rental, library and gift shop all under one nearly 100-year-old roof.

Nielsen and her husband opened the mercantile three years ago as a small grocery store that served rolls and coffee in the morning. “The people accepted us, and we’ve expanded to fit their needs,” she says. And the townspeople have helped by donating freezers, shelving, cabinets, tables, chairs and decorations for the walls.

Nielsen also helped revive the town’s traditional Punished Woman’s Pageant, held in 2010 for the first time in nearly a decade. It commemorates the story of Wewake and her lover Black Bear, both of whom were slain by the tribe’s jealous chief. When homesteaders settled the area in the 1880s, they found stone effigies of Wewake and Black Bear on a hill south of town. Nielsen says they plan to stage a pageant again in two years, but for now a video of the 2010 event is available at the Mercantile.

There’s a brief break in Highway 20 north of Watertown. The route resumes on the city’s west side and loops around Lake Kampeska. It also passes the apex of the triangular Lake Traverse Reservation.

Big Sioux River to the James

West of Watertown, corn and bean fields pockmarked with countless lakes and sloughs dominate the landscape. This is the oldest stretch of Highway 20, which opened in 1929 between Watertown and Highway 45 near Cresbard. In 1944 the highway was extended through Hoven to U.S. Highway 83. In the 1950s a stretch to the Minnesota line was added, and in the 1960s it overtook what had been Highway 8 to Montana. In all, Highway 20 spans 432 miles.

|

| Every town along Highway 20 has an elevator, though Bradley's is long abandoned. |

Grain elevators are prominent in nearly every town from Watertown to the Missouri. Through the wheat belt of Spink County, huge elevators sometimes stand alone. Grain bins greet travelers in Florence, a town rebounding from a devastating fire in June that destroyed an elevator that Terry Redlin used as the backdrop in many paintings. We stopped for root beer at Max Johnson’s Pioneer Cafe, then walked down the block to the elevator’s temporary office where Steve Schlenner was checking markets. Schlenner has managed the Florence elevator for 27 years, and it was he who discovered the fire. Construction crews working on remodeling had left for the day, and Schlenner was running wheat around the large elevator complex when he saw smoke.

“I knew right away it was going to be all gone,” Schlenner says. “I just knew there was no way we would be able to save it. I looked up the chute, and for just a brief second I thought about going up there with a fire extinguisher, but I realized I’d never get it out. It was just a ball of fire. So I dialed 911, and I knew then it was all going to go.”

During our visit, crews busily repaired two adjacent grain bins, and Schlenner said the elevator hoped to be ready to handle the fall’s corn harvest.

Eight miles down the road lies Wallace, birthplace of U.S. Senator and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, though the sign announcing the town’s claim to fame no longer stands along the highway. In Wallace we met Marie Ann Robinson, the state’s only pressed flower artist. She gathers flowers, leaves, fruits and vegetables from her yard and creates award-winning pieces of art.

She showed us a sample of her work. In a Black Hills scene, a flowing waterfall is made from onion membrane, and the rocks are mushrooms. In another, the wooden walls and floor of a weathered building are day lilies. Robinson explained that after they die and are rehydrated, lilies develop a deep brown color and resemble wood grain when pressed. Her interpretation of Henri Matisse’s Woman With a Hat uses peony petals, poinsettia and white poplar leaves. Robinson’s popular South Dakota series includes pheasants, mallards, geese, buffalo and a work in progress featuring wild turkeys.

|

| Marie Ann Robinson turns flowers and plants that grow around her Wallace home into works of art. |

To prevent deterioration, the art is secured with aluminum tape and sealed beneath a layer of Mylar and two pieces of glass. Oxygen absorbers and silica gel packets remove any moisture, so any changes in the botanical material won’t be noticeable for decades.

In the early 1990s, Robinson was arranging wreaths and working with live flowers when she found a lily of the valley pressed in the pages of her grandmother’s Bible. She learned about pressing flowers and began making small bookmarks and magnets (some are for sale at Watertown’s Expressions Gallery, where you can also buy originals or prints of her larger pieces). Then a friend gave her a book on pressed flower art, and she expanded into bigger pieces. She joined an international pressed flower art guild on the Internet, and learns many of her techniques from Russian and Ukrainian artists, including a new framing method that is similar to vacuum packing the art within the frame.

Robinson has lived in South Dakota since 2002, but still speaks with the slight Southern twang she developed growing up in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. She and her husband, a Webster native, lived on an acreage near Clark, where she tended 12 flower beds and a large vegetable garden. But a few years ago she decided to downsize. The flower patch at her Wallace home is considerably smaller, but she still finds what she needs around town and by exchanging materials with fellow artists.

We passed through Bradley and Crocker before arriving in the smallest town on our journey. Just five people live in Crandall, but an old gas station and its summertime music festivals has brought over 3,000 people to town since Dave Swain bought it in 2005. The Pumps was a full-service Standard station opened in 1934 to serve townspeople and passers by on Highway 20, which once ran right past the station (today the road is gravel, and Highway 20 passes 3 miles south of Crandall). When it closed in 1971, it was the last Standard station in the country to use gravity pumps. Standard wanted to include the pumps in a museum exhibit after the station’s closing, but owner Ben Hildebrant produced receipts showing he owned them, and they stayed.

The station was a popular stopping point for motorists traveling from Aberdeen to Watertown. Gov. Sigurd Anderson and Hildebrant were good friends, and the governor often visited. It was also the site of weekly poker games.

Swain opens The Pumps every other Sunday during the summer. There’s no gas, but he sells ice cream, candy bars and pop and displays memorabilia from Crandall’s heyday. One old photo shows the entire town boarding a train for Aberdeen in 1911 to see President Taft. In honor of the 100th anniversary next year, Swain is planning a celebration.

The Pumps is also home to music jamborees, usually one in the spring and another in early autumn. Musicians set up outside and Swain serves a light lunch.

Crandall lies near the western foothills of the Coteau des Prairies, a flatiron-shaped rise across eastern South Dakota. Today giant wind turbines dot the horizon; hundreds of years ago it was a popular gathering place for Indians. Burial mounds and remains of fire rings lie in the hills just north of town. Chief Drifting Goose and his Hunkpati band of Yanktonai were headquartered near here at Armadale, an island in the James River four miles northeast of Mellette that the meandering river has since re-submerged. He’s remembered as a peace-loving chief who preferred pranking homesteaders instead of fighting them. Legend says he once stole the clothes from a settler and made him run back to his sod shanty naked. When railroad surveyors marked the line through his encampment, he moved the stakes. Eventually the railroad was routed through Northville, a more respectful 10 miles west of Drifting Goose’s camp.

|

| Dave Swain bought Crandall's old Standard service station in 2005 and hosts summer gatherings there. The gas is long gone. |

Locals tell Drifting Goose stories with a chuckle, but they also respect the leader who never signed a treaty and, in his mind, never ceded any of his land. No markers commemorate the colorful chief, but Swain is leading efforts to rename the bridge that crosses the James on Highway 20 after Drifting Goose.

When we left The Pumps, we followed Swain through Conde and his hometown of Brentford to tiny Plainsview Cemetery on a narrow, dirt road northwest of town. A few years ago Swain was exploring the cemetery when he found a single, white tombstone that read, “Corp. George W. Melton, 45 Va. Infantry, Co. E, CSA.” After some research, Swain discovered that Melton is one of less than 10 Confederate soldiers buried in South Dakota. He learned that Melton and fellow Confederates Jeremiah Houseman (buried in Mellette) and William Henry Carrico brought their families to Huron from Carroll County, Virginia in 1884. Melton and Houseman both served in the 45th Virginia, while Carrico fought under famous rebel Jeb Stuart at Gettysburg.

The rediscovery of Melton’s grave has led to another mystery around Brentford. Every Memorial Day, an unknown visitor places flowers and a Confederate flag by the tombstone.

The James to the Big Muddy

Highway 20 beyond the junction with U.S. Highway 281 honors another veteran. Cecil Harris grew up near Cresbard, a tidy town in northeastern Faulk County. Harris joined the Navy in 1941 and became the second highest scoring Navy pilot in all of World War II. He once shot down four enemy planes while saving two of his squadron members. Twice more he shot down four planes without taking a single bullet. Harris returned to Cresbard after the war to teach, and eventually became principal at the high school. He rejoined the Navy during the Korean War and served as a career Navy officer. He died in 1981 in Washington, D.C. The state transportation commission renamed the 80-mile stretch of road through Spink, Faulk and Potter counties after Harris in 2009.

|

| Brad and Joletta Naef operate Dakota Jo's cafe in Tolstoy. They serve German food once a week to honor the town's heritage. |

The Harris Highway took us through Onaka and into Tolstoy, where a California couple has opened a new eatery in the town of 36 people. Brad and Joletta Naef moved to Tolstoy in 2009, and last summer they converted the town’s old post office into Dakota Jo’s Cafe. Joletta grew up on a farm four miles northeast of Tolstoy, but Brad is a California native. He was a paint contractor and did light construction, and Joletta managed dental offices. When they retired they wanted a slower pace of life. Their cafe fills a need in Tolstoy and a handful of surrounding small towns.

“We were looking for something to do locally, and she remembered coming to town to the old cafe, so we asked the locals if they’d like a place to meet for coffee in the morning,” Brad says. “And it snowballed into a full cafe. We’re not like Denny’s or IHOP. We don’t even have a deep fryer. We cook like we do at home.”

That means German food in honor of the town’s heritage every Thursday, hot beef combos on Wednesdays, Mexican Tuesdays and a full family dinner on Sundays. The cafe is decorated with items from their home in California; his mother’s plates and her grandmother’s tin can art adorn the walls. They revel in the solitude they have discovered in Potter County. “Where we came from, you’d have bars on the windows and alarms all over,” Brad says. “I used to wake up two or three times every night. Now she can’t shake me awake.”

The spires of St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church in Hoven loomed high above the horizon for miles before we passed through town. West of Hoven, U.S. Highways 83 and 12 join Highway 20 on its final jaunt through East River. Next to a cornfield south of Selby we found the Bangor Monument, a tribute to the town that was Walworth County’s seat from 1884 to 1909, when it was moved to Selby.

|

| Rodney and Sheryl Stroh converted Selby's old Amoco service station into a gift shop and restaurant. |

Tall cedar trees surround the century-old grand brick courthouse in Selby. On the southeast corner of the courthouse square stands a monument to Capt. Newton Kingman, a Civil War veteran and one of Selby’s founders. Kingman placed two Civil War cannons on the square, but they were melted during World War II. In 2000, Justin Randall raised money to buy a replica cannon and placed it atop a brick and concrete pedestal. The project earned him an Eagle Scout badge.

We met Justin’s mother, Sheryl Stroh, at Dakota Maid, one of Selby’s newest businesses. Stroh and her husband Rodney operated a gift shop in the basement of their home but soon ran out of space. “I knew the gift shop wouldn’t support itself if we rented a building,” she says. “So then we thought we’d do a coffee shop and maybe a few panini sandwiches.”

They bought the town’s old Amoco service station along the highway in 2009 and created Dakota Maid, which has become a full service restaurant, coffee shop and gift store featuring South Dakota made products, like Valiant Vineyards wine and chocolate from the Watertown Confectionery.

Beyond Selby, Highway 20 winds through the grassy mounds of the Missouri River valley and through Mobridge, our final destination. It crosses the Missouri River near its confluence with the Grand River and continues west, through the Standing Rock Reservation and ranch country before ending west of Camp Crook. We heard there’s a unique town market in Trail City, that the country between the Grand and Moreau rivers includes some of the state’s best scenery, and that if you pass the Castles of Slim Buttes in just the right light, they resemble medieval ruins. That’s a trip for another time.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2010 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

Just wanted to add that my great grandfather, Henry Kahre, who is buried in the St. John Lutheran Cemetary, just southwest of Wolsey, is also a Civil War Veteran. He served with the E Company, 4th Regiment of Indiana.

Again, thank you for sharing the backroads history of South Dakota

at that time. I was borne in Faulkton on December 19 1929. My parents had a farm about five or six miles north of Tolstoy, which farm my younger brother now owns. Dakota Jo's is very dea rto my heart