The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Wheat Ritual

|

|

|

Teams of combines often assemble to harvest the sprawling fields of Sully County, easily the wheat capital of South Dakota. Farmers there generally plant more than 230,000 acres of wheat. In 2007 they grew 10.5 million bushels. Photo by Dave Tunge. |

Dakota Wheat Field

By Hamlin Garland

Like liquid gold the wheat-field lies,

A marvel of yellow and russet and green,

That ripples and runs, that floats and flies,

With the subtle shadows, the change, the sheen,

That play in the golden hair of a girl, -

A ripple of amber — a flare

Of light sweeping after — a curl

In the hollows like swirling feet

Of fairy waltzers, the colors run

To the western sun

Through the deeps of the ripening wheat.

Wheat is just dark bread to most Americans, but it encompasses history, geography and a way of life for thousands of South Dakota farm families who harvest 3.5 million acres in summer rituals that connect us to the very first homesteaders.

The grain harvest was once a community event, as families joined forces for the labor-intense binding, shocking and threshing. Today, lone farmers race across wheat fields in gleaming and computerized five-ton metal combines with GPS systems and air conditioned cabs that harvest more than 100 acres on a good day, but the principle remains the same as when the work was done by hands and horses.

|

|

Modern combines eliminate much of the toil and tedium from the wheat harvest. Still, a flurry of activity can be seen in farm country as the heads ripen and droop with grain. |

“Like liquid gold the wheat field lies,” wrote pioneer Hamlin Garland, a Dakota homesteader who later became a popular American novelist. Garland found farm life tedious, but he appreciated the beauty of a ripening wheat field and the bounty that it represents.

West River cowboys and city residents who haven’t experienced the appeal of harvest might compare it to the satisfaction of the last day of a good school year, to the serenity of a hike in some quiet woods, or to the success of a roundup when every cow and calf is accounted for.

Cultivation of wheat began 10,000 years ago when the Neolithic people of Asia began to replant wild grasses and collect the seeds for food. European emigrants brought seeds overseas. Today 10 percent of the world’s 22 billion bushel wheat crop is grown in the United States, mostly in the six prairie states that stretch from the Dakotas to Texas. South Dakotans raise and harvest about 76 million bushels every summer.

Corn, soybeans and cattle are economically more significant statewide, but wheat is still king to some farmers in north central South Dakota. John O. Overby homesteaded in Spink County near Northville in 1883, and then moved to a farm east of Mellette in 1886. He and his wife raised five sons who became wheat farmers. Overbys have lived in the same farmhouses and planted the same fields for five generations.

“When they first came here, wheat was the predominant crop,” says Glenn Overby, today’s patriarch. “Of course everybody had some livestock but wheat was the big cash crop into the 1940s.”

|

|

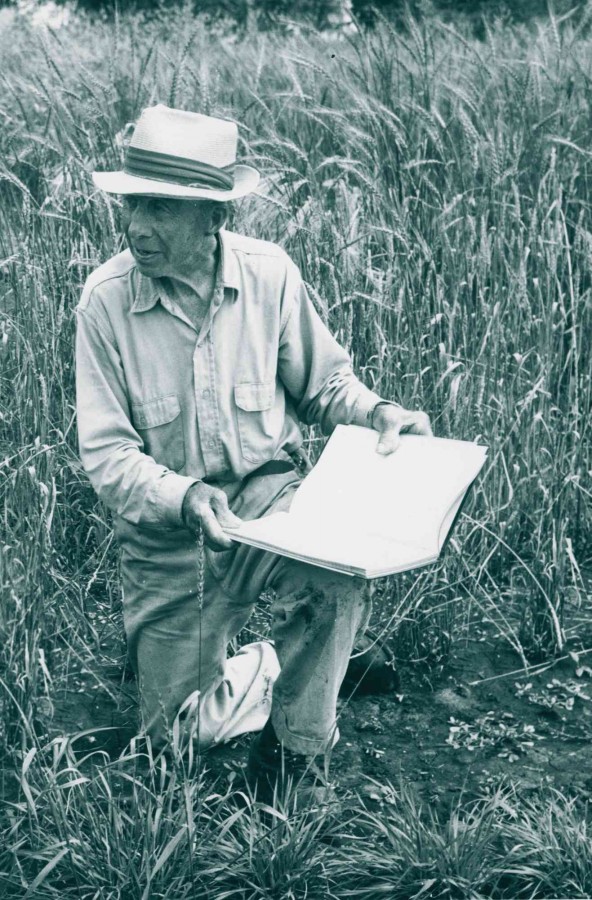

Humans have been planting and harvesting wheat for 10,000 years. Glenn Overby was raised in a family that was devoted to perfecting wheat and other aspects of farm and ranch life. |

The Overby brothers owned an Avery threshing machine. “It took 12 bundle racks to keep it going with spike pitchers,” Glenn says. “We had a cook car in the yard. Can you imagine all the bread they had to bake and all the chickens they had to butcher to just feed the workers?”

Tom Kilian, a longtime Sioux Falls educator and conservationist, grew up on a Miner County farm where threshing was a summer highlight. In his 2007 book Old Days on the Prairie, Kilian recalled the quick pace. “All the tasks were performed as fast as possible and this provided opportunity for the more macho of the young farm hands to demonstrate muscle,” he wrote. “Who could load and unload the fastest? Who could get out to the field, load up and come back the quickest, driving the most spirited horses? And who could do those things with flair and careless energy so as to stand out in the group?”

Despite the size and speed of today’s combines, a sense of urgency still surrounds the harvest. Any change in the weather — wind, rain or hail — might dramatically decrease the yield. Though a field may be golden brown and heavy with heads of grain, farmers don’t consider it a success until it is harvested and hauled to the safety of a steel bin either on the farm or at a local elevator.

Even then, there’s the question of price. Wheat milling, like meat-packing and other food processing industries, has experienced massive consolidations in the last half-century. More than 1,200 mills competed to buy wheat in the heydays of the 1940s; today fewer than 400 operate, and they are generally located near metropolitan populations far from the prairie wheat fields. That leaves farmers dependent on the vagaries of a less-competitive market, and also on the resourcefulness of the railroads to move the grain out-of-state.

Despite such uncertainties, South Dakota farmers carry on the 10,000-year human tradition of planting and harvesting wheat. The Overbys have always exemplified the determination to continue our wheat-growing ways.

Glenn’s dad, John, wanted better yields and more consistent quality. He had a South Dakota farmer’s healthy aversion to the commercial seed companies so he experimented for decades with his own seed plots. He kept extensive records, handwritten in pencil.

|

“Creating a new wheat variety is a long process,” says Glenn, who has all the record books, as well as an understanding and appreciation for what his dad accomplished. “First, one needs a vision to pick the varieties that have the qualities wanted in the new plant. Wheat has both male and female parts in each kernel’s blossom so it is self-pollinating. Before the female blossom is mature the three male antlers must be removed by opening the hull with a tweezers to take them out,” he says. “Several days later, when the male blossom ripens the pollen sacs are transferred by tweezers to the female blossom. When the pollen is mature it is only viable for about five minutes so timing is critical.”

His dad cross-pollinated up to 100 different plants a year using 10 to 15 kernels each. The selection process occurred when he planted the hybrid plant the next year. It took between seven and 10 years for him to get enough grain to just do a milling and baking test.

The Mellette farmer-scientist had only an eighth grade education but he learned agronomy from reading books. “Dad was interested in getting a better variety for himself and his neighbors,” said Glenn. “He wasn’t interested in starting a big business. He wanted a high protein wheat with a strong stalk that didn’t shatter or shell out too easily, was drought resistant and disease resistant.”

The work was so exacting that he insisted on doing it personally, but the entire family lived with the experiments. “When he harvested he would pull the wheat stalk out by the roots because he wanted to see how the root was growing. He would tie a single row into a bundle and 20 rows into a larger bundle. In two rooms upstairs, he stored the bundles, threshed each row in a box with a wood block, weighed, recorded notes, evaluated and decided which to continue crossing or discard for the next year.”

He devoted 50 years, often on his knees with a tweezer, to improve the tradition of growing wheat ...

John Overby started his experiments in 1915 and by 1928 he was selling his own variety, Marvel Wheat, for $2 a bushel. Because of Marvel’s high protein and test weight it sometimes sold for 50 cents more per bushel than other kinds of wheat.

The part-time plant breeder developed another variety known as Spinkcota and gradually he attracted loyal customers. Glenn helped his father clean wheat seed and loaded it for customers. He remembers when the well-known Asmussens of Agar became the first farmers to buy more than 100 bushels. “We loaded their truck and took it to the Mellette elevator to weigh and then they stayed for lunch,” he says.

Farmers believed Spinkcota had higher yields and was better suited to the South Dakota soil than its corporate competition. Ralph Sorensen, the Spink County extension agent in the 1940s, became a believer and he got the attention of Darrell Wells and other plant scientists at South Dakota State College in Brookings.

When academic researchers reported at a Minneapolis milling and baking conference that Spinkcota was not a favorite among commercial bakers, Sorensen retorted that the South Dakota seed had endured the 1953 rust epidemic better than the competition and that farmers were developing quite a liking to the variety.

As Overby was nearing the end of his career, he witnessed the beginning of what is now called the green revolution. Wheat yields doubled in the 1960s and 1970s due to an expansion of modern farming practices, better seed varieties and the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. A leader of the movement was Norman Borlaug, an Iowa-born scientist who — like Overby — saw farming as a way to improve the world.

|

|

Ruth and Glenn Overby (far right) live in the house where Glenn’s father experimented with wheat varieties. Pictured with them are their son, Philip, his wife, Linda, and grandson A.J., who represents a fifth generation on the same farm. |

Overby grew test plots even as an old man, and he continued to gain respect from both his neighbors and the agricultural community. In 1962 the Brentford Congregational Church held a John Overby Appreciation Banquet. Charles Croes, the first leader of the South Dakota Wheatgrowers Cooperative, was one of the dignitaries who came to pay tribute. “Probably one of man’s most tragic shortcomings down through the ages has been his lack of interest in doing something for the benefit of his fellow man, his neighbor, without being first assured that he would profit money-wise for the doing,” Croes said. “The richer reward, the knowledge that his action has helped his fellow man, has been all too often overlooked, given second place or lost entirely.”

Not John Overby, however. He devoted 50 years, often on his knees with a tweezer in his fingers, to improving a South Dakota wheat-growing tradition that was in its infancy during his lifetime.

Glenn and his wife, Ruth, live on the farm where the test plots were raised and bundles were stored and inspected. They have all of John Overby’s journals and records, and many of his tools and memorabilia.

Their son, Philip and his wife, Linda, live just across the grove of trees. Philip farms the land today, with help from Linda and their son, A.J., who studies agriculture at SDSU and represents the fifth generation of Overbys to harvest wheat in Spink County.

“In many ways it’s the same even though the equipment has changed,” Glenn says, as he watches Philip cross a field in a combine that moves like a ship at sea, only noisier and dustier. The sky over Spink County is a deep blue, contrasting with the golden wheat stalks and green corn in the neighboring field.

The land here is so flat that you can see another combine a mile away, sailing above its own square sea of wheat. Nothing is certain in life, but the Spink County wheat harvest has become a predictable summer rite thanks to families like the Overbys who have tended to both the land and the custom.

Overby Inventions Exhibited at SDSU

|

John Overby’s creative mind roamed well beyond plant breeding. He and his brothers invented several farm improvements, and some can be seen at the State Agricultural Heritage Museum in Brookings.

Curator Dawn Stephens says the Overby inventions include a windmill regulator, a stock waterer, a contraption that mounted on the wheel of an automobile to harvest small grains and, naturally, a better mouse trap.

Stephens assisted the Overby family in producing a documentary, “John Overby: Wheat Breeding Methods,” that can be purchased for $15 at the museum (or by phone at 688-5904). “He and his brothers were very inventive. I can’t believe the things they thought to make,” she says. “And they were not afraid to voice their opinions and stand up for what they believed in. They worked hard to make farming life better.”

The ag museum, located on the South Dakota State University campus, also has antique wheat harvest equipment such as a Norwegian hand crank thresher, an 1890 Case Agitator with original paint, a Massey combine, an IH grain binder and a 1915 John Deere hay press that still works.

The museum staff will play the Overby film for visitors upon request.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2009 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call 800-456-5117.

Comments