The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Watermelon Capital

Editor’s Note: Forestburg is our Watermelon Capital, as we discovered when we visited Levo Larson, the self-proclaimed “Watermelon King,” in the summer of 1997. Levo has since passed away, but Forestburg melons are a South Dakota tradition that will long endure. This story is revised from the July/August 1997 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Salesmanship and showmanship are rare commodities in agriculture these days. Farmers send their crops to market and seldom get an encouraging or discouraging word from the final consumer.

That, perhaps, is part of the attraction to the watermelon industry that has sprung up in Sanborn County. Several dozen farm families devote their summers to the back breaking, sweaty tasks of planting, hoeing and harvesting several thousand acres of watermelon. They say it's all worthwhile when the customers flock to their roadside stands in late summer as predictably as the waterfowl who soon follow in the fall.

The tiny town of Forestburg has laid claim to the title of South Dakota's watermelon capital. Nobody has challenged for the title. Nobody is competing. There aren't many other places where an entire rural neighborhood wants to work that hard to make a few thousand extra dollars.

"Everything with melons is pretty much hand done. It is a lot of work," agrees Dorrie Tollefson, who married into the business 19 years ago. "But I like meeting people. We're our own boss. It's all I do for a job."

For Tollefson and her neighbors, the melon trade has been successful because of geographic good fortune, namely the James River and State Highway 34. Sandy soil in the river valley gives the melons their sweetness and the highway provides a steady stream of buyers, especially during the last week of August when thousands of cars drive by daily en route to the South Dakota State Fair at Huron.

"We measure our melon crop by how much we sell during fair week," says Tollefson.

That's where showmanship enters into the business. Farmers who might not normally paint their barn go to great lengths to create a folksy, country look to their roadside watermelon stand.

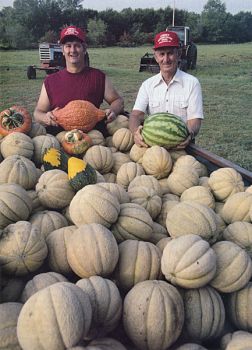

Melon decor ranges from gaudy colored lights to wagon wheels and scarecrows. But over time, the produce itself has proven to be the best car-stopper. Melons are piled high in mounds. Splashy orange pumpkins, earth-tone gourds and enough colored corn to decorate a palace wall in Mitchell are common to most of the roadway markets.

"Appearances are very important," says Charlotte Nelson, who runs Nelson's Melon Stand along with her husband, Bud. "I decorate with banners. We use corn and hay bales, pumpkins and gourds and whatever else looks good."

Levo Larson and his son, Skip, stop motorists with red, white and blue wagon wheels, an old red pump, flashing lights and an American flag waving in the breeze.

Levo has learned the art of salesman-ship better than most. He is the self-proclaimed Watermelon King and his stand is named accordingly. You'll find him in the Forestburg phone book under that title.

Levo has been raising melons for 45 years. For several decades, he entered his produce in the state fair and won many honors. But he says the best test of any melon farmer is repeat customers.

"There is a hell of a lot of work and hand labor that goes into growing these. They don't just spring up on the shelf," says Levo. "But a lot of the people thank you for doing it; and that's something you don't hear as a farmer too often."

For thousands of Midwesterners, the traditional end-of-summer excursion to the state fair wouldn’t be complete without a stop at a Forestburg watermelon stand. Mark Twain called watermelons "the fruit of the angels" and obviously their reputation hasn't soured since his time.

Some customers will buy the first melon they see atop the pile. "Others will thump a dozen or more before they find one they like," laughs Mrs. Nelson.

Thumping is a layman's test of whether the melon is ripe. A hollow sound means "get the knife." However, professional melon growers are divided over the best way to judge ripeness. "Once you've raised them for awhile, you can tell by the color," says Mrs. Nelson.

Forestburg farmers say customers don't need to test their melons for ripeness because they won't bring them in from the field until they are ready for eating. "It hurts our pride to pick a green watermelon," says Levo. "We guarantee ours to be ripe and we guarantee them to have Vitamin P if you eat enough."

The thumping no doubt comes from customers' experience with store-bought melons. Imported melons from southern states are often picked "pink" rather than vine ripened.

In Poor Richard’s Almanac, one of the sayings suggests, "Men and melons are hard to know." Melons aren't that difficult, however, according to Skip Larson. "I look for the little curl beside the stem. If it is dry the melon is ripe."

His dad says ripe melons also have a chalky look. A melon that needs more time on the vine will have a shiny appearance.

Another trick of the trade at Forestburg is crop rotation. "Watermelon shouldn't be planted on the same ground more than once every five years," says Skip. "The melon takes the sugar out of the ground and if you don't rotate you won't have the high sugar content."

Customers often think the Forestburg melons' sweetness comes from the seed so they save seeds for replanting. Bad idea. "If you save the seed you'll have a watermelon that tastes like a cucumber from cross pollination," says Levo.

Experienced growers buy nothing but the best hybrid seeds at $180 a pound and more. Favorite varieties for Forestburg include the round, dark Black Diamond and the striped Crimson Sweet, Sangria and All Sweet.

The Larsons grow the smaller King and Queen melons for area Hutterite colonies, who pickle them whole in 55-gallon barrels along with garlic, dill, salt, vinegar and water.

The real secret to good melons is the same as real estate - location, location and location. "You can get out of this area and raise big watermelons but they don't have the sweetness or flavor," says Skip Larson. "It's something about the sandy soil."

Melon growing presents challenges different from corn and bean farming. Striped, yellow beetles will eat small watermelon sprouts if they aren't controlled. A hailstorm wreaks havoc when the melons are formed. The hailstones cut holes in the rind and cause the fruit to go sour.

Rabbits, deer and raccoons are also a threat. They love to dine on ripe melons. To keep them at bay, the state Game, Fish and Parks Department loans propane-powered boom guns that are designed to "pop" every three minutes and scare wildlife away from the fields. Sometimes on a still day in late summer, Sanborn County sounds like a battlefield.

About 2,000 acres are planted to melons in a 12-mile square between Forestburg and Woonsocket. Most of the small melon fields drain into Sand Creek, which runs into the Jim River at Forestburg.

Of course, the coincidence of having State Highway 34 running right through melon country has encouraged the profession. Motorists during State Fair week in late August haul away half the annual harvest. That's followed by the annual Corn Palace Festival in Mitchell, which is almost as busy.

In the 1930s, when Ernie Schwemle and Harold Smith first started raising melons commercially, it wasn't nearly as easy to find local buyers. They hauled them by wagons to the railroad at Cuthbert or Woonsocket for shipment to grocery stores in bigger cities.

Ray Baysinger constructed one of the oldest stands during the early 1950s in the shade of the big cottonwood trees a few miles west of Forestburg. Now known as Ron's Melon Stand, the Peterson family operates it.

Some of the melons are still sold wholesale to area stores. Most growers also sell at a discounted price to people who resell them out of the back of their pickup in their hometown. "People in their 50s or 60s, retired from their regular job, will do it for entertainment and a few extra dollars," says Skip.

Most stands remain open throughout October to catch pumpkin buyers. Prices for melons drop as the days grow shorter and colder.

Some customers drive long distances just for the sweet melons. The Larsons once had a customer from Tyndall, two hours to the south, during fair week.

"Going to the fair?" Skip asked.

"No, we just came for melons," was the reply.

That's music to the ears of Forestburg farmers.

Though experts say watermelon tastes best right from the vine, cooks have been turning the juicy, summertime treat into everything from pickles and preserves to pastries.

Here's a few new ways to enjoy watermelon, courtesy of the National Watermelon Promotion Board.

Watermelon Smoothie

2 cups seeded watermelon chunks

1 cup cracked ice

1/2 cup plain yogurt

1 to 2 Tbsp. sugar

1/2 tsp. ground ginger

1/8 tsp. almond extract

Combine all ingredients in blender; mix until smooth. Makes 2 to 3 smoothies.

Fresh Watermelon Salsa

2 cups watermelon, seeded and chopped

2 Tbsp. chopped onion

2 Tbsp. water chestnuts

2 to 4 Tbsp. chopped Anaheim chilies

1 Tbsp. balsamic vinegar

1/4 tsp. garlic salt

Combine all ingredients; mix well. Refrigerate for 2 hours; add more balsamic vinegar to taste. Serve with grilled chicken or nachos.