The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Who Lies in the Custer Graves?

|

| Six members of the Seventh Cavalry, dead since 1873, lie in the Bon Homme Cemetery, though their identities and their exact connection to the Seventh remains a mystery. |

On a summer’s evening in 2011, a retired stonemason from Yankton toiled on his hands and knees in the Bon Homme Cemetery. Behind him stood a cracked granite tombstone marking the graves of six men whose brief sojourn through Dakota Territory in the spring of 1873 gave rise to legend and mystery.

The men are said to be soldiers from Lt. Col. George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry, who passed through Dakota on a 400-mile march from Sioux City to Fort Rice, south of present-day Bismarck, North Dakota. An inscription on the stone reads, “In memory of six unknown soldiers,” because the men were apparently hastily buried and left with no indication of who they were.

After the cracks on the gravestone were repaired, we began to think more about the men buried in its shadow. It seems a cruel fate to lie anonymously for nearly 150 years in a prairie cemetery far from your home and family. Because of Custer’s ignominious end at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, and his regiment’s later presence at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, he and the Seventh are among the most researched and written about soldiers in the United States. Could it be possible to find mention of the six men who died along Snatch Creek and end their century and a half of anonymity? As it happens, we aren’t the first to try.

Our search began at the University of South Dakota’s I.D. Weeks library. The second floor houses microfilmed rolls of the Yankton Daily Press & Dakotan, which began publication in June of 1861, making it the oldest newspaper in the Dakotas. A weekly paper in 1873, its April 16 issue included an announcement of the Seventh Cavalry’s arrival on the outskirts of town beginning April 9.

The Seventh had been created during an Army reorganization after the Civil War and tasked with protecting settlers, travelers and railroads as they filtered into the Great Plains. George Armstrong Custer, still known throughout the country for his heroics at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863, was chosen to be its lieutenant colonel. The new unit was based at Fort Riley, Kansas, and while it had been designed to be a peacekeeping force, the Seventh became embroiled in more than 40 fights with Indian tribes in the three decades after its inception, including the infamous Battle of the Little Bighorn in June of 1876 that decimated the Seventh and killed Custer.

In 1873, the Seventh was reassigned to the Army’s Department of Dakota, with orders to depart Fort Rice in northern Dakota Territory on an expedition along the Yellowstone River during the summer. The War Department began planning the Seventh’s springtime route from the southern United States to Fort Rice. It included an encampment of several weeks either in Sioux City, Iowa, or Yankton to allow time for prairie grasses to grow enough to feed the livestock.

Yanktonians can thank Walter Burleigh, the town booster and often-unscrupulous politician and businessman, for bringing Custer their way. Burleigh was a Pennsylvania native and a Republican who helped Abraham Lincoln win the state in the election of 1860. As a result of his new connections in Washington, D.C., Lincoln appointed Burleigh to be the Indian agent for the Yankton Sioux Reservation in Dakota Territory.

He used his position to line his pockets whenever possible, and that remained true in 1873. Burleigh had purchased a steamboat, the Miner, several years earlier, and stood to profit nicely if he could convince the War Department to use his boat to carry supplies for the Seventh up the Missouri River from Yankton to Fort Rice. He also owned land east of Yankton near Rhine Creek (today called Marne Creek) that would support a spacious campsite for the regiment’s 800 soldiers, 40 laundresses, 700 horses and 200 mules. Burleigh successfully lobbied military brass all the way up to General Phil Sheridan, commander of the Division of the Missouri. When the final plans were revealed, they included a stay at Yankton.

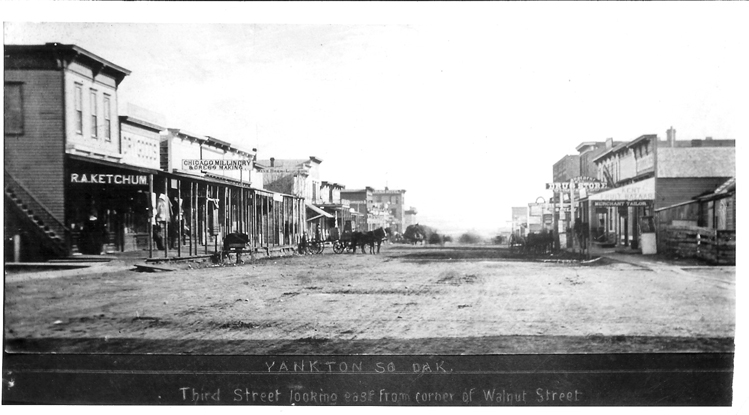

|

| Yankton's Third Street, pictured in 1875, appeared much as it had when Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer's Seventh Cavalry paraded through two years earlier. The Seventh spent nearly a month encamped east of Yankton on its way to Fort Rice in northern Dakota Territory. Photo courtesy of the Dakota Territorial Museum. |

In the days after the Seventh arrived, a city of tents sprang up on the prairie about a mile east of Yankton, just across Rhine Creek. The camp had barely taken shape when a severe spring blizzard (still known as the Custer Blizzard), nearly buried it under several feet of snow.

Several soldiers made it into Yankton before conditions worsened. They sought shelter for their horses, then found their way into the saloons and hotels along Third Street. But there were many other soldiers, wives and laundresses who hunkered down under blankets as the snow slowly weighed down their canvas tents. Custer and his wife endured the storm inside a log cabin, which they had rented from a local upon their arrival.

The storm slowed business to a trickle for several days and pushed the Seventh’s scheduled departure into early May, as they waited for the snow to melt and the grass to turn green. The delay allowed the citizens of Yankton to host a ball for Custer and his officers on the second floor of Stone’s Hall at Third and Capital. Felix Vinatieri, Yankton’s town bandmaster, assembled a group of musicians to provide entertainment. The talented Vinatieri, a graduate of the music school at the University of Naples in Italy, played every instrument except piano. Custer noticed his vivacity, and asked if he would serve as the Seventh’s chief musician on their journey to Fort Rice.

Vinatieri accepted, and when the Seventh finally departed on May 7, he led a 16-member band as the cavalry paraded from their campsite down Third Street and west out of Yankton along the Sioux City to Fort Randall Military Trail. Burleigh’s Miner was loaded with the regiment’s supplies and followed the column upriver.

The Press & Dakotan reported that the first day’s march took them to Lakeport. The second day, the regiment advanced to Owen’s Ranch along Snatch Creek, 19 miles from Yankton. But flooding had swelled both Emanuel Creek and Chouteau Creek farther west. Custer sent soldiers ahead to bridge both waterways, and the Seventh was delayed.

Soldiers tried to make the best of the delay. Local women brought fresh bread and kolaches, a traditional dessert from their native Czechoslovakia. Soldiers and their wives spent time aboard the Miner, which anchored along the riverbank not far from camp each night. Custer and his wife, along with several officers, took meals daily at the Cogan House, a hotel in the village of Bon Homme run by Bridget Cole Cogan, an Irish immigrant.

Finally, after four days, the regiment continued its 400-mile march to Fort Rice. What they left along Snatch Creek became a local legend and a mystery that remains unsolved.

|

| Greg McCann's Cogan House overlooks the Missouri River not far from where his great-aunt, Bridget Cogan, housed Custer and his officers. |

Greg McCann is the great-nephew of Bridget Cogan. Her hotel and restaurant stood just a few hundred yards northeast of the current Cogan House, a bed-and-breakfast and hunting lodge that McCann and his late wife, Diana, built along a Missouri River bluff in 2008.

His riverfront property has seen plenty of history over the last 225 years. Lewis and Clark paddled past in 1804. Private Shannon, a member of their Corps of Discovery, famously became lost a short distance downstream and was reunited with the group near the mouth of the Niobrara River. Several years later, trappers like Jim Bridger and Hugh Glass followed the same path, as the Missouri River became a highway of sorts.

McCann also knows well the story of the Seventh Cavalry’s visit. He says during their delay, Custer and his officers entertained the people of Bon Homme with shooting contests (they were reportedly good shots). According to his family’s oral history, a depression in the earth just a few paces from the modern day Cogan House marks the site where Custer himself camped, chosen because of its ideal views of the river, the military trail and the village of Bon Homme.

As a caretaker of the Bon Homme Cemetery, he also knows the story of the six soldiers who supposedly contracted typhoid fever and died at the regiment’s main encampment along Snatch Creek. According to local legend, two graves were quickly and quietly dug on the creek’s western bank. Six of the men were buried in one and an officer named Abraham Hirsch was supposedly placed in the other. The regiment moved north the next day, and the bodies remained there until 1893, when they were disinterred and moved to the Bon Homme Cemetery. In 1922, William Thomas Harrison crafted the large tombstone that was carefully repaired in 2011 by Yankton brickmason and historian Bob Hanson and his friends.

The identities — and even the correct number — of the soldiers interred there have stumped historians for decades. For years, Abraham Hirsch was believed to have been an officer in the Seventh Cavalry. But Mark Chapman, of the Seventh United States Cavalry Association, says no Abraham Hirsch is listed in the regimental records. Similar searches by historians in the National Archives also come up empty.

When South Dakota historian Herbert Hoover wrote his history of Bon Homme County, he found paperwork that showed $6 paid for a coffin for A. Hirsch, but the date was April 17, 1873, nearly a month before the soldiers died at Snatch Creek. Given the evidence, it seems likely that even though Hirsch has long been associated with Custer’s soldiers, he was not part of the Seventh.

As for the other six, the only accounts of their deaths seem to be in the stories that have been passed down through the generations. Chapman says there are no deaths recorded in the May 1873 regimental record (although it does note 46 desertions). Only five fatalities were noted during the months in which the Seventh was transferred from the South and sent to Fort Rice: one in Charlotte, North Carolina; two en route from Memphis to Cairo, Illinois; one between Louisville, Kentucky, and Cairo; and one on May 4, when Private William Donovan of B Troop drowned.

|

| Retired Yankton stonemason Bob Hanson repaired the worn and cracked Custer tombstone in 2011. |

Contemporary accounts are equally fruitless. The Press & Dakotan reported on such details as the songs played during the grand ball in downtown Yankton, but after the regiment moved out information grew scarce. The newspaper told readers about the delay along Snatch Creek, but said nothing about the deaths of six soldiers. Its final mention of the Seventh came on June 18, with a report that the regiment had safely reached Fort Rice.

Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, wrote about the trip through Dakota in her memoir called Boots and Saddles. Her chapter describing the march out of Yankton focused on subjects such as the cold weather, wildlife, food preparation and sleeping accommodations. Second Lieutenant Charles Larned wrote regular letters home to his mother during the journey from Sioux City to Fort Rice and provided articles for the Chicago Inter-Ocean. Neither penned a word about any soldiers dying.

So if other deaths were reported in the regimental record, why the secrecy surrounding the men who died along Snatch Creek? McCann was always told Custer wanted the deaths kept quiet because if word leaked that he had lost six men, it would reflect poorly on his leadership. Another argument is that medical records were only sporadically updated while the regiment was on the move. For example, in their new book called Health of the Seventh Cavalry, P. Willey and Douglas Scott note that the number of men who suffered frostbite and endured subsequent amputations during the Custer Blizzard at Yankton was far more than what the record actually reveals. Several soldiers in the early stages of frostbite stumbled into the Custer cabin, where Elizabeth Custer helped treat them, yet those and other cases are absent from the official record.

But the most widely accepted theory is that Custer did indeed want the deaths kept secret, though for a different reason. The regiment relied heavily on cooperation from local settlements throughout the journey to Fort Rice. Custer was concerned that if word of a contagious disease such as typhoid fever within the Seventh became public, friendly relations with both Indians and non-Indians could be compromised. It seems the success of the march took precedence over the memories of six soldiers.

Bon Homme Cemetery lies along the bluffs of the Missouri River, on a county thoroughfare quaintly named Apple Tree Road. It was established in 1859 and is the final resting place of several Czechoslovakian pioneers who began trickling into southeastern Dakota Territory in the 1860s.

Local families keep the grounds and the graves well tended — including the anonymous Custer six. McCann believes if they can confirm that the men belonged to the Seventh Cavalry, federal funds may be available to help maintain the cemetery, but so far all paper trails have gone cold. And it’s not as though no one has tried. Hazel Belle Abbott, a Bon Homme County native who earned a Ph.D. at Columbia University, spent her last years compiling a history of the county and tried earnestly to uncover more information about the Custer soldiers, but could never identify them. She died in 1971, and her research is housed in the state archives in Pierre, waiting for someone else to build upon it.

Perhaps somewhere a family diary notes a son or brother who marched off with the Seventh and never returned. But for the citizens of Bon Homme County, the six bouquets of flowers and American flags that decorate each grave have always been — and may continue to be — “in memory of six unknown soldiers.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2016 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments