The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Woman Behind the Mountain

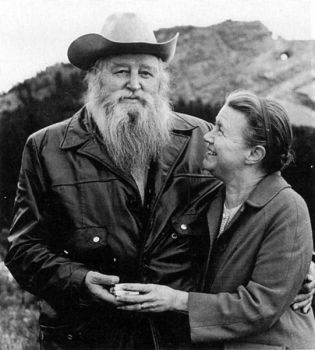

Editor’s Note: All of South Dakota was saddened to hear of the death of Ruth Ziolkowski, who passed away May 21, 2014, in Rapid City at age 87. She first arrived in South Dakota in 1948 to help sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski begin his monumental carving of Crazy Horse. The two were married in 1950. After Korczak’s death in 1982, Ruth steadily guided work on the mountain. She will be missed, but her legacy will live at the mountain forever. This story originally appeared in our May/June 1995 issue.

Ruth Ziolkowski has emerged from the shadows of her late husband, Korczak, to become one of South Dakota's best-known and busiest women. She supervises the world's largest sculpture, 563 feet high and 641 feet long. Yet, she presides over the project and a large family with a gentleness that belies her toughness.

I drove to Custer recently to meet Ruth and learn about her work. Although it was a raw spring day, I first went to Thunderhead Mountain to see the carving. There were more mountain goats than carvers on the rocks. Crewmembers were warming themselves in an equipment building and passing around a new Weekly Reader that described their work.

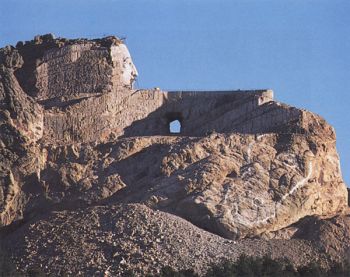

Articles like that have become commonplace. Korczak's sculptural design became well known to South Dakotans, and many Americans, long before any features were discernible on the granite outcrop. Crazy Horse sits astride a great horse, and he points to the southeast where his people's dead lie. The design is increasingly recognizable worldwide as a mighty statement about the strength, pride and historical tribulations of American Indians.

Journalists from everywhere document the crew's progress (the day before my visit, a French TV team wrapped up a shoot). For years it was standard practice to photograph the mountain with a model of the finished sculpture in the foreground. But not anymore. The mountain carving has begun speaking for itself.

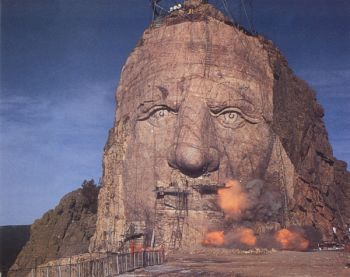

The crew went back to its tasks, one of which was preparing to blast a pie-shaped section of rock from Crazy Horse's left jaw. A few feet from there, from a point on the rock that will be cut away to shape the outstretched arm, the face's appearance is startling. No longer is it a generic mask, but a Lakota face with cheekbones, strong nose, and furrowed brow. The head is cocked slightly to the left; Ziolkowski noted that people usually tilt their heads when they point.

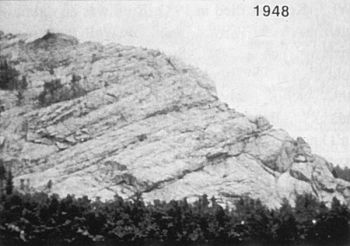

Just this spring it was announced the 87-foot face will be completed by June 3, 1998. That will be the 50th anniversary of the date when Ziolkowski set the first blast on the mountain, in front of an audience that included five Battle of the Little Bighorn survivors. The completion will put the project nearly two years ahead of its goal of finishing the face by the turn of the century, attributable largely to recent mild winters. Work this past winter progressed, too, on Crazy Horse's chest, the right side of his head, and on the horse's mane.

I caught up with Ruth Ziolkowski a couple hours later in her home below the mountain. Between fixing lunch and taking phone calls, she recalled her husband's first years here.

"He knew right away how big the carving would be in physical terms, but the job in human terms he didn' t know until he had worked on the mountain for awhile," she said. "Can you imagine starting to work on that mountain by yourself? Building steps up there, carrying up all the equipment on your back? Most anybody would have quit, but he didn't."

Ruth described herself as the project's "chairman of the board, but I do the dishes, too."

Self-effacing humor and a gentle manner mark Ruth's interaction with the public and her workers, long-time acquaintances say. But make no mistake, they quickly add — she is in charge.

"When Korczak died in 1982, Ruth was an unknown quantity to the public," said Robb DeWall, the project's communications director. "Some people wondered what would happen to the sculpture, though people who knew Ruth were completely confident she'd continue her husband's work. But the public didn't know her then, and we didn't know the skills of the children."

Seven of Ruth and Korczak's 10 grown children are part of the Crazy Horse project. On this day three — Mark, Anne, and Monique — stopped in for lunch, along with the 10-year-old granddaughter, Heidi. Around the table, with the potatoes and corned beef, was passed a Weekly Reader, and someone mentioned that the mountain came up on Carmen Sandiego, the TV geography show, the day before. Then the table talk drifted to a discussion of the type of crane needed for completing the Native American Educational and Cultural Center, under construction next to the house.

Everyone has his or her own area of responsibility. Mark oversees forest management on the 1,200 acre Crazy Horse site and builds roads. Anne is director of the acclaimed Indian Museum of North America here, and is in charge of the gift shops that feature Native American products. Monique, who is winning recognition as a sculptor in her own right, is the Crazy Horse pointer, meaning she takes precise measurements from points on her father's model and calculates how much rock must be removed from corresponding points on the mountain. Other siblings direct services for 1.3 million visitors annually, work on the mountain, and perform daily behind-the-scenes duties.

"I'm lucky," Ruth told me. "My children are working with me. Every one of them went off and did something else for awhile, but seven came back here. We've all grown in our jobs."

Korczak was nearly 40 when he began Crazy Horse, and early on he drew up plans for continuing the work after his lifetime.

"Leave it to Korczak to look to the future," said Ruth. "He would have been a great chess player, always planning a couple moves ahead."

But when you're sculpting a mountain, even detailed plans don't mean you simply check off completed tasks and move on to the next. "There's a lot to learn as you go, and that's the challenge, the fun," Ruth said. "For everything you finish, about three more jobs come along."

There are always decisions to make about how much revenue should go into the sculpture, and how much should support visitor services. The project is also committed to a scholarship program that's the forerunner to a university and medical center Korczak envisioned here. Since 1978, 800 Native American students have benefitted.

For the past few years Crazy Horse has worked with an annual budget of a bit more than $1 million, mostly raised by admissions to the grounds and concessions. The Grass Roots Club, with members who support Crazy Horse with $25 dues each year, contributed $133,000 in 1994.

Even occasional revenue windfalls mean hard choices, though. Additional money might allow for more mountain carvers. But more workers mean more equipment, and that equipment will need maintenance in the future; where that maintenance money will come from has to be considered now.

By far the most difficult decision Ruth has made was when she determined, in 1987, to make Crazy Horse's head the focus of work, rather than the horse's head. It was the right call, gaining the project greater credibility as the facial features emerged. Fewer and fewer comments are heard along the lines of one that CBS newsman Charles Kuralt heard in Rapid City several years ago. A rental car clerk told Kuralt that Korczak Ziolkowski was perpetrating a scam, living well off admissions, and blasting a little rock now and then for effect (Kuralt didn't buy it, and ended up staying several days with the Ziolkowskis that trip and reporting on the carving's development several times over the years).

Confront people who said Crazy Horse was a scam a few years ago, and they'll say that thinking was understandable if you compared Mount Rushmore's progress to Crazy Horse's. Rushmore, even with chronic funding problems and crew layoffs, was brought to its present state in 14 years. The Crazy Horse folks, after four decades, could claim more than eight million tons had been blasted away, but could point to nothing resembling a chief on a horse. Crazy Horse supporters, in the early years, were quick to respond that work on Thunderhead Mountain was a privately funded, one-man show, while Rushmore had taken federal funding which supported over 300 carvers during its creation. And then there's the size. The four Rushmore heads combined could fit into the area planned for Crazy Horse's head.

"Korczak never liked those comparisons, because that's not what this carving is about, and it's not what Mount Rushmore is about," Ruth said. She added Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum was among three personal heroes Korczak claimed, along with Michelangelo and da Vinci.

Her husband, Ruth said, knew it would have been easier to sculpt a mountain away from the object of comparison (Rushmore is 17 miles up the highway) but that was never a possibility because the Black Hills were Crazy Horse's native land.

In 1939 Korczak worked part of a season as a Rushmore carver. Also that year, his marble Paderewski: Study of an Immortal won first prize for sculpture at the New York World's Fair. That publicity, combined with the fact that Korczak knew something of mountain carving because of Rushmore, led Lakota chief Henry Standing Bear to approach him about Crazy Horse.

About the same time a teenage girl showed up at Korczak's West Hartford, Connecticut home hoping to get an autograph from movie star Richard Bennett, who was visiting. The girl was Ruth (then Ruth Ross) and she would volunteer to help Korczak as he sculpted a Noah Webster statue in Connecticut a couple years later. As a college student she would come to South Dakota with a group to assist with the very first work at Crazy Horse in 1947.

"Back in those first years here, he never said if the sculpture is completed," Ruth recalled. "It was when the sculpture is completed. So people around him, and visitors, talked that way, too. That was the power of his personality."

Ruth and Korczak were married in 1950. In a way, Ruth also found herself married to the mountain and surrounding Hills. She receives many invitations, but has no desire to leave home even for brief trips. And the Black Hills are home; she hasn't been back to her native Connecticut since 1962.

"I like being surrounded by evergreens year-round," she said. "Besides, like Korczak always said, wait and eventually everyone you'd ever want to meet will come here."

It proved a prophetic statement. Artists, politicians, reservation school kids, and vacationers from around the globe all make the trek to Crazy Horse. Ruth doesn't get up on the mountain often. "I told Korczak I'd keep Crazy Horse together as an organization, but I can't carve a mountain," she said. "So when I go up, it's just to see. I'm not about to tell anyone where to drill, or blast, or anything else."

She has, she said, complete confidence in her children who work on Thunderhead Mountain and in the crew. And her thoughts when she visits?

"It's absolutely amazing to see, but I'm like Korczak," she said. "There's never been a time I didn't think it would happen.”

Comments