The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Slight of Hand

|

| Luigi Del Bianco, an Italian stone carver from New York, served as chief carver on Mount Rushmore. After years of lobbying by the Del Bianco family, Luigi was honored on Sept. 16 with his own plaque at the national monument. |

Editor’s Note: Luigi Del Bianco, chief carver on Mount Rushmore, was officially honored for his work on the monument with a special ceremony and the unveiling of a plaque on Sept. 16. Here is our story about Del Bianco and his grandson Lou, who worked for years on his family's behalf to ensure that Luigi was recognized for his important role in creating the national monument. The story is revised from our May/June 2014 issue. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

In 1985 Rex Alan Smith published The Carving of Mount Rushmore, considered by many Rushmore researchers to be the definitive account of how perhaps the greatest sculpture in the world emerged from Black Hills granite. Smith expertly details the struggles between temperamental sculptor Gutzon Borglum and the Mount Rushmore Memorial Commission, which oversaw the project. There are stories from the men who worked on the mountaintop and the boosters who navigated Mount Rushmore through its darkest days, knowing it would transform South Dakota forever.

Nowhere in the book’s 416 pages of narrative, photographs, bibliography and index will you read the name Luigi Del Bianco, a classically trained Italian artist specifically recruited by Borglum to be the monument’s chief carver from 1933 to 1940. When Del Bianco’s son Caesar and grandson Lou read Smith’s book, hoping to learn more about Luigi’s contributions to the memorial, they were astonished to find nothing. “He was really the artist who brought the faces to life,” Lou Del Bianco says. “The workers did a wonderful job roughing them out, but you need an artist to bring out the emotion in the faces, and that’s what my grandfather did.

“It’s like leaving Joe DiMaggio out of a book about the New York Yankees. It’s like he wasn’t even there.”

So the Del Bianco family embarked upon a mission to give their patriarch the recognition they believe he deserves for helping create one of the world’s most familiar monuments. Their quest has taken them to Mount Rushmore, on several trips to the Library of Congress and up the ladder of the National Park Service, seeking to change years of firmly held policies regarding how the men who made Rushmore are credited — all to little or no avail. After 25 years of lobbying, it leads to one question: Was Luigi Del Bianco just another laborer on the mountain, as his absence in the book suggests, or should he be credited as the man who brought Mount Rushmore to life?

Lou Del Bianco was 6 years old when his grandfather died of silicosis, a deadly lung disease contracted after decades of inhaling microscopic particles of silica sent airborne as he carved stone. It’s especially cruel that a man’s lifelong avocation and passion would eventually cause his death. When Luigi Del Bianco was born in tiny Meduno, Italy in 1892, it seems he was destined to carve stone. A family story says that as a boy Del Bianco made a small dog from a piece of wood. His father, also a carver, was so impressed that he sent his son to a school in Austria that offered general studies and special courses in stone carving.

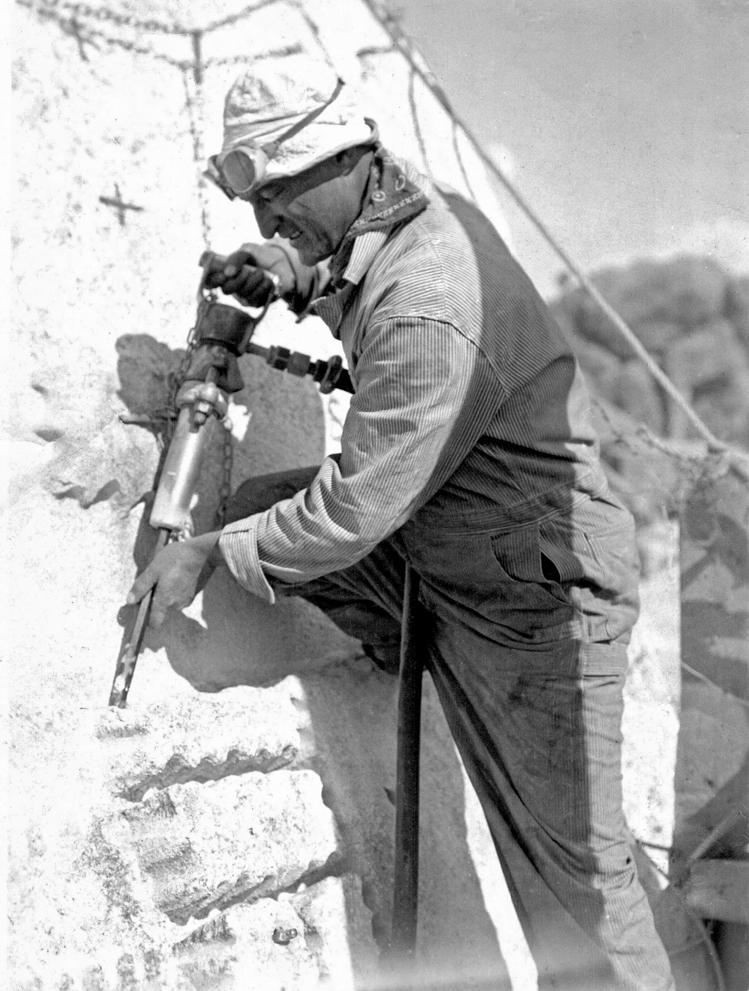

|

| Del Bianco patched a portion of Jefferson's lip when workers encountered a dark strip of feldspar. |

Del Bianco stayed in Austria as an apprentice after graduation and spent time studying classical art and architecture in Venice before immigrating to the United States. He had been born into a long line of carvers, and he had many cousins working in a quarry in Barre, Vermont. He joined them in 1909, but returned to Italy to fight with the Italian Army in World War I. Del Bianco immigrated to America permanently in 1920.

As he toiled in the Vermont quarries, he became friends with another stonecutter named Alfonso Scafa from Port Chester, New York. Scafa had cut stone for Gutzon Borglum, who had a studio in nearby Stamford, Connecticut. “You should meet Borglum,” Scafa told Del Bianco, “because you have a lot of talent.”

The two artists were introduced and forged a lifelong friendship. Del Bianco moved to Port Chester, and after meeting and marrying Scafa’s sister-in-law, Borglum offered to house the newlyweds for a year in the honeymoon cottage on his estate.

Del Bianco began a monument company in Port Chester, but he also developed a working relationship with Borglum that lasted 20 years. “They argued quite a bit, but it was part of their relationship,” Lou Del Bianco says. “They had great mutual respect for one another, and in the end they loved each other.”

The artists worked together on the Wars of America memorial, a huge bronze in Newark, New Jersey, that honors the country’s war dead. Because of Del Bianco’s well-defined Roman facial features, Borglum used him as a model for 20 of the 42 human figures depicted in the piece.

Borglum also brought Del Bianco to Georgia to work on Stone Mountain. The project on the outskirts of Atlanta was supposed to be Borglum’s crowning achievement. In 1915 the United Daughters of the Confederacy asked Borglum to carve a likeness of Gen. Robert E. Lee into the face of the granite uplift. It may have seemed an impossible notion, but the idea suited Borglum perfectly. He believed that American art should be, “built into, cut into, the crust of this earth so that those records would have to melt or by wind be worn to dust before the record could, as Lincoln said, ‘perish from the earth.’”

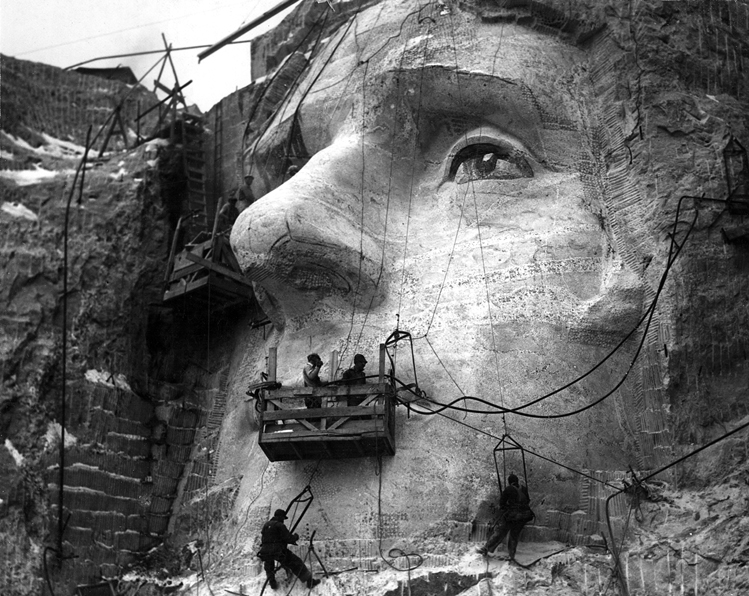

|

| Del Bianco carved Lincoln's eyes with a clever trick that Gutzon Borglum knew would give them life. |

Borglum had an even grander vision for Stone Mountain, and planned an elaborate carving of Lee with a column of Confederate soldiers. Work began in 1923, but constant disagreements between Borglum and the Stone Mountain Association combined with a lack of funds led the artist to leave the project in 1925. Fortunately for Borglum — and eventually for Del Bianco — Doane Robinson had already contacted the artist about a new project in the Black Hills.

Robinson, South Dakota’s state historian, wanted something that would bring people to the Hills. He envisioned full-length likenesses of the country’s founding fathers carved into granite spires called the Needles. Robinson was aware of Borglum’s work at Stone Mountain and invited the artist to scout locations in the Black Hills.

After a few visits Borglum abandoned the idea of carving on the Needles and settled instead on the granite of Mount Rushmore. He fashioned a scale model of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln and devised a method to transfer its measurements to the mountaintop. With a skeleton crew of fewer than two-dozen men, the first bits of granite were removed in October 1927.

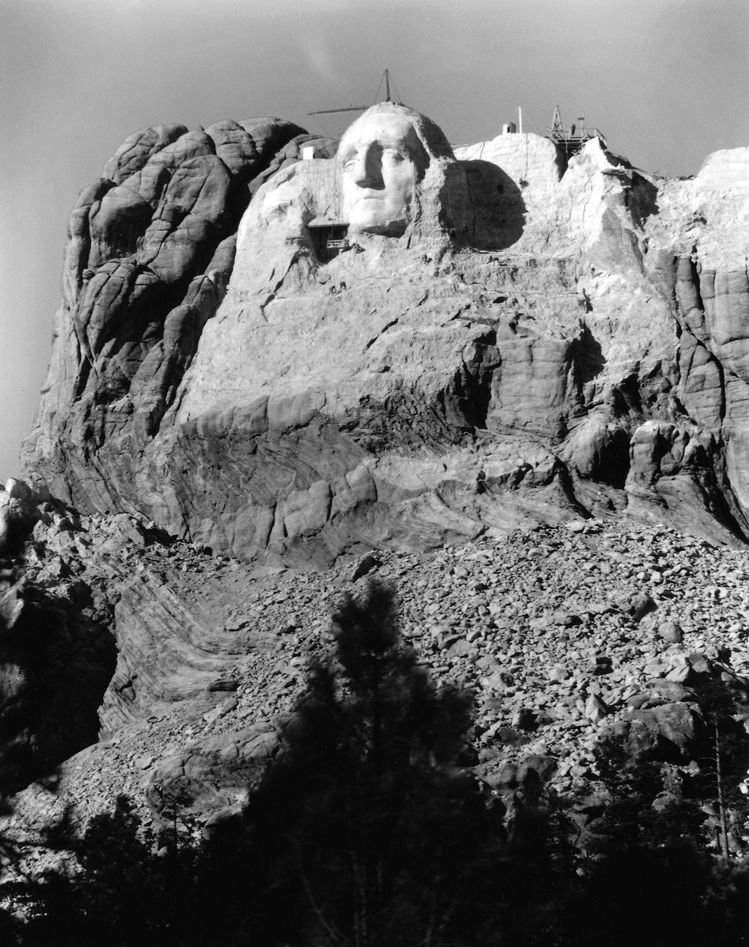

Work progressed slowly until 1929 when Borglum hired a crew of former miners to help rough out the heads. Rex Alan Smith described what a visitor to Mount Rushmore in 1930 would have seen: “you can tell that it is supposed to be Washington, but the face is heavy-featured and lumpish and the eyes are not yet alive, nor the mouth. It appears that way to others, too, and as [Congressman] William Williamson has just noted in his diary, ‘It lacks expression. It is little more than an image in its present state. Power is lacking.’”

Borglum knew it too. “Somebody has to put life and expression into carved faces,” he said. “That’s why more good mechanics don’t turn out to be good sculptors.” He needed someone who understood the art of stone carving and could make the granite faces seem to gaze over the landscape. He thought he found the right man in Hugo Villa, another Italian sculptor who had assisted Borglum in Connecticut. But Villa soon became one of many men who resigned over wage disputes during the 14-year project.

In 1933 Borglum offered the chief carver’s job to Del Bianco. “It was something only an artist could do,” Lou Del Bianco says. “A lot of the other workers were involved in rough cutting the features, but the chief carver brought refinement of expression. There was only one chief carver on the whole work, and that was Luigi.”

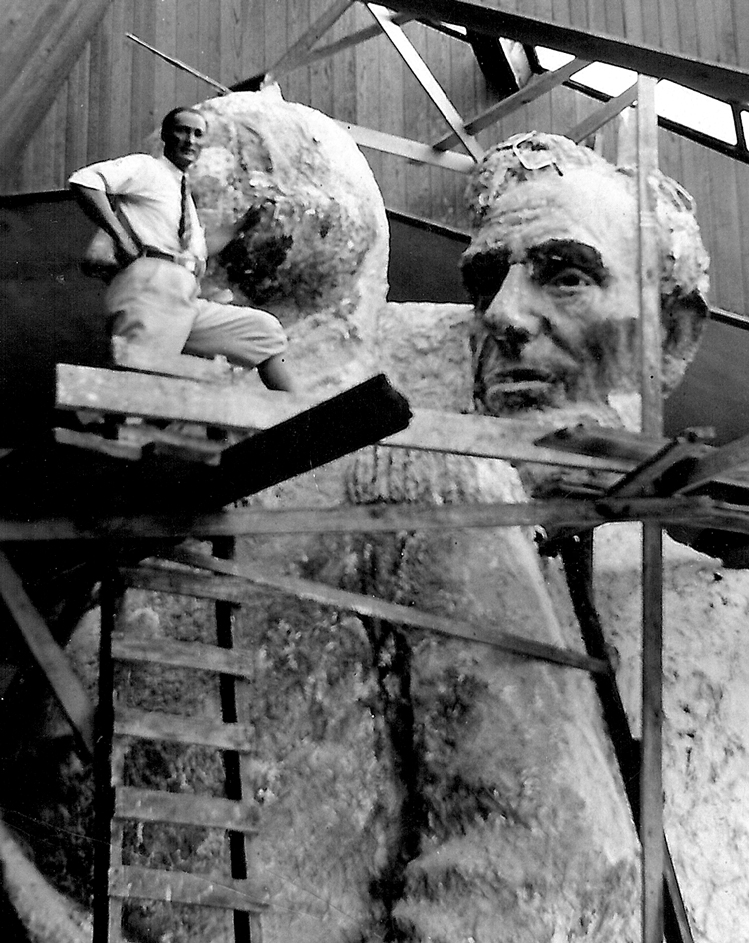

|

| Del Bianco helped transfer measurements from Gutzon Borglum's model to the mountaintop. |

Borglum was convinced Del Bianco was the man for the job. “Bianco has all of Villa’s ability plus power, honesty and dependability,” he wrote to the Mount Rushmore commission. “We could double our progress if we could have two like Bianco. Now I have decided we must keep Bianco and keep him happy. If he were working for me I would pay him eleven or twelve dollars. I want him to receive a dollar an hour. You may charge me with the difference. The help he is, the ability to understand is worth much more to the work.”

Del Bianco spent eight seasons working on Mount Rushmore. In 1935 he moved his entire family — which included wife Nicoletta and sons Silvio, Vincent and Caesar — to a cabin in Keystone with mixed results. “My grandmother did not like living out there, being uprooted from her New York family and friends,” Lou Del Bianco says. “Culturally it was a shock to her. She was always frustrated because they had no Italian ingredients for her meals. But the people were always very accommodating and thoughtful.”

The boys — especially Vincent — adapted to life in South Dakota quite well. They rode horses, swam in Battle Creek, attended a one-room school with the children of other Rushmore workers and became friends with Native Americans. For the rest of his life, Vincent proudly displayed the scar on his thumb, evidence that he had become blood brothers with an Indian boy. “He had wonderful memories of living how he supposed people had lived in pioneer days. He did not want to come back to New York.”

Nevertheless, when the 1935 season concluded, the Del Bianco family returned to New York and Luigi alone came every summer through 1940, staying at a small boarding house near the foot of Mount Rushmore. He worked on refining the Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln heads and quickly gained Borglum’s trust. “He is worth any three men I could find in America,” Borglum wrote. “He entirely out-classed everyone on the hill, and his knowledge was an embarrassment to their amateur efforts and lack of knowledge, lack of experience and lack of judgment. He is the only man besides myself who has been on the work who knows the problems and how to instantly solve them.”

Del Bianco’s problem-solving abilities were challenged when workers roughing out the Jefferson head encountered a dark strip of feldspar on the upper lip. Left untreated, millions of future visitors would get the impression that Jefferson had a cold sore. Del Bianco instructed the men to cut out the dark stone. Then he used a piece of granite from the rubble pile below the carving and shaped it to fit the space. Today the repair is hardly detectable, even to the maintenance crews that regularly inspect the heads.

Perhaps Del Bianco’s greatest contribution, and a point of pride until the day he died in 1969, was carving Lincoln’s eyes. Borglum put great thought into making Lincoln’s eyes as lifelike as possible. “Constantly sketching in a notebook whose tooled leather covers were worn by time and use, he studied the Lincoln head in the angled light of dawn, the brightness of midday, the shadows of evening,” Smith wrote. “He studied it from viewpoints in the canyon, Mount Doane, and the tramway cage. He viewed it from his studio window and, as ideas and inspirations came to him, he telephoned instructions from there to Lincoln Borglum on the mountain or even directly to carvers on the Lincoln head. Much of this time and study he devoted to Lincoln’s eyes and to the special method by which he was to give them, as well as those of Rushmore’s other figures, a lifelike quality rarely seen in sculpture.”

|

| Del Bianco returned often to his home in Italy to visit family, including cousin Luigia Del Bianco. |

Borglum’s plan was to carve each pupil several feet across and deep enough to always be shadowed. In the middle, he left a rectangular shaft of granite. Their tips catch the sunlight, and from a distance provide sparkle to Lincoln’s eyes.

Borglum relied on Del Bianco to carry out the vision. “I could only see from this far what I was doing, but the eye of Lincoln had to look just right from many miles distant,” Luigi told an interviewer in 1966. “I know every line and ridge, each small bump and all the details of that head so well.”

Borglum’s intent for Mount Rushmore was to carve the figures to the waist, but plans changed upon his death in 1941. Money was again scarce and it seemed ever more likely that the United States would enter World War II. That summer work on Rushmore stopped for good, and the 400 men who helped create it slipped into obscurity. “There was public recognition of the leaders,” Rex Alan Smith wrote. “Borglum was made a national figure because of his Rushmore work, and he knew that so long as the monument should endure, he would be immortalized as its sculptor. [Sen. Peter] Norbeck, [John] Boland, and the others also received public credit while the work was going on, and knew, as well, that their names would be indelibly written in its history. Rushmore’s workmen, on the other hand, were anonymous. The newspapers did not know their names, nor would the monument’s future viewers. They were Rushmore’s unknown soldiers, and they knew it.”

After Mount Rushmore, Luigi Del Bianco returned to Port Chester. He carved over 500 headstones that still stand in cemeteries in New York, Connecticut and New Jersey. He also created art; mostly busts and human figures that today belong to his descendants and private collectors. A permanent exhibit of his work is housed in the Italian American Museum in New York’s Little Italy. He spoke rarely about working on Rushmore, and after his death his family knew few details. His only grandson and namesake first discovered the connection when he found an old Mount Rushmore brochure that belonged to Luigi. “I was such a shy kid but I wanted right away to tell my second grade class about it,” Lou Del Bianco says. “I combed through the pages looking for him and couldn’t find him. I just wanted to find his face or an image of him at the mountain, and he wasn’t there.”

|

| As Washington's face emerged from the mountain, observers noted that it lacked expression. "It is little more than an image in its present state," said Congressman William Williamson. "Power is lacking." |

His grandfather’s role at Mount Rushmore was little more than a conversation starter until Lou was in his 20s and began talking to his uncle Caesar, who wanted to know more about what his father had done. That’s when they discovered Smith’s book — with its emphasis on former miners and no mention of Luigi. “That really raised a red flag with us,” Lou says. “That’s only part of the story. They had to be trained, had to be instructed. And it wasn’t only Gutzon Borglum, but my grandfather was also a main teacher of these men.”

They traveled to Mount Rushmore in 1988, but found nothing in records housed at the memorial. Then they met Howard Shaff, who had recently finished his biography of Gutzon Borglum called Six Wars at a Time. Shaff directed the Del Biancos to the Library of Congress, which houses Borglum’s papers. As they dug through the folders, finding letters written by Borglum praising Luigi, they gained a clearer picture of his importance to Rushmore. “He wasn’t just the chief carver,” Lou says. “He was vital to the work. When Luigi would quit over wages, Borglum would say that all work has to stop.”

Luigi’s daughter Gloria attended Mount Rushmore’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1991 and met George Rumple, who started on the monument in 1932 and was a foreman when work ended. “He was not only a stone carver, he was a genius,” Rumple said of Del Bianco. “He was one of the top men. I think he could have taken Mr. Borglum’s place and completed the monument himself.” Now the Del Bianco family was beginning to realize how important Luigi was to the creation of Mount Rushmore. They just had to share it with the world.

Every year, roughly 2 million people stroll up the Avenue of Flags toward perhaps the greatest sculpture in the world. On the way they pass a shiny stone slab on which are etched the names of 395 people who worked on Mount Rushmore. Luigi Del Bianco’s name is in the second column, 13th from the top. It’s in accordance with National Park Service policy.

“We try to recognize all the different workers on the monument,” says Maureen McGee-Ballinger, chief of interpretation at Mount Rushmore. “Mr. Del Bianco had significant contributions, as did William Tallman and Lincoln Borglum. There were many people involved in the sculpture, and if you think about it, 90 percent of the work was done with dynamite. So the people who drilled the holes and placed the dynamite were also significant workers.”

Lou Del Bianco offers an expected and politically correct response: “I respectfully and stridently disagree with policy, and I hope to change it.” He becomes more passionate as he explains his family’s position. “My biggest argument is that you have to stop calling him a worker,” he says. “He was a classically trained artist that Borglum brought in. For the past 25 years they’ve basically said that they just don’t give one worker credit over the others. So a gentleman considered a worker who ran the elevator tram that hauled supplies to the top of the mountain is being put into the same category as my grandfather, and that to me is just not right.”

|

| Lou Del Bianco created a one-man show about his grandfather's time working on Mount Rushmore, which he performed at the monument during the summer of 2011. |

At the same time, Del Bianco doesn’t want to give the impression that he’s trying to overshadow Borglum. “As much as I know my grandfather was a big part of Mount Rushmore, Gutzon Borglum was the vision,” he says. “He’s the reason there is a Mount Rushmore. My grandfather idolized him.”

Luigi Del Bianco still looked up to the man he called “the master” even in old age. “It was a sad, sad day when my master died,” Del Bianco said in 1966. “The world lost a great genius.”

Still, Lou Del Bianco thought he might be making headway in 2011. He works as a storyteller, creating shows for elementary school audiences around the Northeast. He wrote a one-man show about his grandfather called “In the Shadow of the Mountain” and spent a day performing it at Mount Rushmore. “There was a very palpable response from tourists and even the rangers,” he says. “They’d come up afterward and say they had no idea. They would go over to the big plaque with the workers’ names and point him out. They all promised they would talk about him more in their walking tours. I really felt like we were making some headway, but that all just shut down. The Mount Rushmore people have all been cordial and very polite to me, but they are holding fast to their policy that there’s no ‘I’ in team.”

Despite the setback, Del Bianco won’t quit because he can sense support from his grandfather. “I think he’d be thrilled,” he says. “And I think I figured that out at Mount Rushmore the day before my performance. I went to the sculptor’s studio where he worked with Borglum measuring points and talking. Borglum talked to my grandfather all the time to bounce ideas off him. All the tourists were milling around, and there’s a giant window toward the monument next to the models. I looked up at the faces and realized, ‘I’m really here. I’m going to do this show, and I’m going to bring him to life.’ And for a second I saw him up there on a scaffold, nodding his head and saying, ‘Thank you.’ I just lost it. I broke down and cried. It was a huge release of tension. I felt like I got my answer from him.”

Interest in Luigi’s story is accelerating. Lou Del Bianco wrote a screenplay that he is currently shopping and a book about Luigi is scheduled for release in 2014. Mount Rushmore’s Joe DiMaggio may finally get his due.

Comments