The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Apostles on the Plains

|

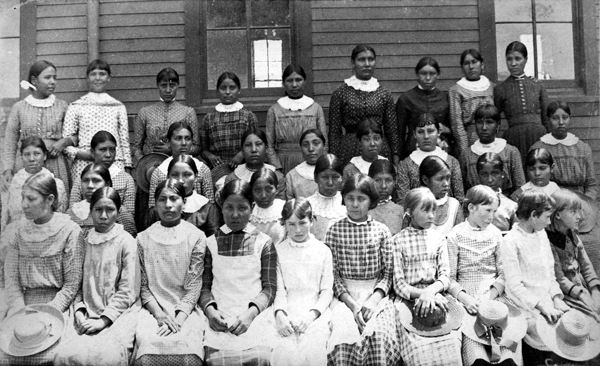

| Thomas Riggs established Oahe Industrial School in the 1870s as a training school for girls. Funding difficulties forced it to close in 1904, but local support had helped it reopen for a brief period when this photo was taken three years later. |

Stephen Return Riggs was determined to spread the Gospel just as his forebears, “a long line of Godly men,” had done. His only question was whether to head for the American West, or to China. Like most missionaries of the era Riggs thought the first would present greater hardships, so in true apostolic spirit he chose that path.

Stephen married Mary Ann Clark Longley on Feb. 16, 1837, and within a month they left their Ohio home for Lac Qui Parle Mission, amongst the Dakota Indians in what would one day be Minnesota. There were unevangelized souls aplenty in the neighborhood, but Riggs couldn’t rest knowing there were more just beyond the horizon. In the fall of 1840 Stephen headed west, crossed the Missouri River in a bull boat and delivered a sermon at Fort Pierre — the first documented Christian service in the future state of South Dakota.

“We communicated to them something…of the good news of salvation,” he recalled, though he also concluded, “we could not do much, or attempt much, for the civilization and Christianization of those roving bands of Dakotas.”

That would be left to the next generation.

Mary and Stephen Riggs brought eight children into this world. Three followed in their parents’ footsteps. Alfred, the first born, spent most of his working years as an educator among the Santee in Nebraska; Isabella, the eldest daughter, left for a mission in China on the day after her marriage and didn’t return for 30 years. Thomas Lawrence Riggs, the fifth child, born June 3, 1847, would one day return to where his father first preached to the Lakota.

The Riggs children grew up at Lac Qui Parle surrounded by, but purposely kept separate from, the surrounding native community. “Our children are in danger of becoming little Indians in their tastes, feelings and habits,” wrote Mary to her parents back East. That prospect horrified her, but she need not have worried: her children were equally appalled by their environment. Alfred remembered that growing up at the mission, “caused such a disgust for everything Indian that it took the better thought of many years to overcome the repugnance thus aroused.”

|

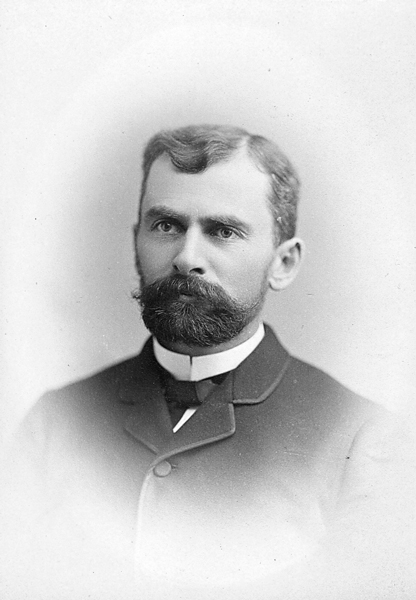

| Thomas Riggs established Oahe Mission in 1872 and labored there for almost 50 years. |

Stephen labored for years to bring written Dakota to life, but he refused to let his children learn the language while they were young lest they be contaminated by “impure thoughts and impure words.” When Thomas took his entrance examination for Beloit College in 1863 he was found to be exceptionally well-versed in Greek and Latin — he was more fluent in the languages of long-deceased Aristotle and Caesar than in the one spoken just beyond the door of his family home.

Over the years, three generations of the Riggs family lived, worked and made friends with many Dakota and Lakota, yet they never entirely lost their “us and them” attitude regarding the Indian people. They were hardened in that way of thinking by the traumatic events of 1862. Simmering Dakota resentment over white encroachments on their land and the theft of treaty goods reached full boil in late August, when the murder of a settler family by an Indian hunting party galvanized the tribe’s young, restless warriors to strike back against the whites. Roving war parties put scores of Minnesota River valley farms and settlements to the torch; more than 400 soldiers and settlers were killed, and thousands more fled in terror to better-protected towns. Among those put to flight were the Riggses, who traveled six days before finding safety at Shakopee.

Stephen Riggs assisted the commission which sentenced 39 Dakota to death after the uprising; he also ministered to the condemned men while they were being held awaiting execution. If he felt any disquiet about performing two such contrary functions he never expressed it, and his dual roles were, in a sense, symbolic of the family’s ongoing involvement with the Dakota and Lakota. Stephen, Alfred and Thomas Riggs devoted most of their working years to evangelizing and educating the Indian people, but they did so seemingly without remorse for their part in displacing the native culture, and for the pain and havoc such a drastic change wrought all around them.

Thomas Riggs left Minnesota for Beloit College after the uprising, and upon graduating in 1868 spent a year in Mississippi “attempting to be a teacher,” as he put it, “but I soon learned I was not likely to be a success at the profession.” He thought about architecture as a career, then rather abruptly changed the course of his life by enrolling at the Chicago Theological Seminary.

As a young man, Stephen Riggs experienced a profound spiritual awakening and divine call to the ministry. Thomas received no such summons — at least not from on high. He entered the seminary even though he admitted no particular inclination to missionary work, and when he recalled in his memoirs how he set upon this path, Thomas Riggs did so in one cryptic sentence: “In accord with father’s plan, I was to enter a new field among the Teton, or Prairie Dwellers, on the Upper Missouri.”

Thomas and his younger brother Henry established Hope Station, on the Missouri’s west bank across from Fort Sully, in 1872; they later relocated to the east bank about five miles above present-day Oahe Dam, midway between villages of the Two Kettle and Sans Arc bands. (This mission, originally known as Bogue Station, was later christened Oahe, after the Lakota name for the place.) Their new building had a large school room/chapel and kitchen on the first floor and family quarters that Thomas now needed on the second.

Thomas met Cornelia “Nina” Foster while he was in the seminary, and they married on Dec. 26, 1872, in Bangor, Maine. She came from a home of comfort and refinement, yet adapted readily to the rough conditions of Dakota Territory. Nina gave birth to their first child, Theodore Foster, two years later. The blessed event was accompanied by a nearby war party’s drum and random gunfire, one round of which tore through the home’s roof and lodged in the rafters. Their second son was stillborn in 1878, and thereafter “our dear one sank gradually out of reach,” wrote Thomas to his father. Nina was buried in the mission house yard, before her favorite window.

|

| Elizabeth Winyan (standing) had a long association with the Riggs Family. She cared for young Thomas in Minnesota, and later joined him at Oahe Mission. |

By 1877 the Oahe congregation had outgrown the first floor meeting room and Thomas decided the mission needed a proper chapel. Lumber arrived on a steamboat captained by legendary river pilot Grant Marsh, and before long a “sweet-voiced organ” and bell donated by the Central Congregational Church of Bangor rang out across the prairie, drawing the faithful to Lakota language services. (Oahe Mission is covered by Lake Oahe today, but the chapel was salvaged and moved to the Oahe Dam visitor center; the organ is in the Cultural Heritage Center in Pierre.)

With Oahe’s spiritual side accommodated, Thomas Riggs turned to education. A workshop was established to teach the men carpentry skills, “but the shavings underneath do not prevent study. All begins with the A B C,” Thomas reported to the mission’s donors back East. “We have to teach them other things as well — the women to wash and iron and the men to work. The gospel of cleanliness is emphatically taught. When a dirty hand is put out to take a book the boy is told to wash himself. A woman is advised to comb her hair, another is told to wash her gown and to clean her house.”

Classes were held in the chapel to start, and in due time Oahe Industrial School got a two-story frame building that could accommodate 50 girls for classes in academic subjects and “the domestic arts.” Boys were admitted later, and the school reached a peak enrollment of 70 pupils in the 1890s. Funding the operation was an ongoing problem, however: when the American Missionary Association withdrew support in 1904, the school was forced to close its doors.

Attendance at the Oahe Mission services was “fitful and uncertain, [one day] a full house and then but one or two dirty children,” recalled Thomas. “Then, as they would not come to us, I went to them.”

|

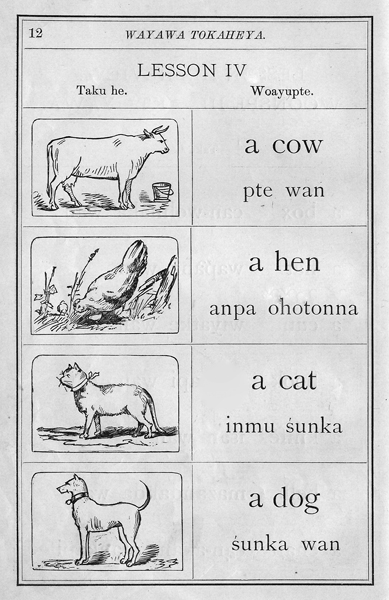

| Riggs and Dr. Thomas Williamson translated the Bible and a school textbook (above). |

In his time at Oahe, Thomas established 25 meeting places at settlements across the far-flung Cheyenne River Reservation. Making one circuit of these outstations meant a round trip of over 500 miles. Thomas also traveled to missions as far east as Sisseton, south to Crow Creek and north to Fort Yates. In one stretch he averaged an amazing 6,000 miles a year, mostly across trackless open country.

The treks were demanding and, at times, dangerous. On one trip to Sisseton with his eldest son they made camp after fording the James River, “and in the morning we could smell smoke,” recalled Theodore. “As we drove on our way we could see that there was a real fire off to the northwest, driven by a fairly strong wind…When the fire came upon the high land where we could see the flames, father stopped the team, got out of the buggy and set a fire of our own. When we were sure that the ground had cooled enough so as not to be too hot for the horses’ feet, we turned, and going far enough to be out of the heat of the main fire, we waited until it had passed.”

On another trip to see his brother Alfred, Thomas and his team went through the Missouri River ice near Springfield. He made it to shore and somehow righted his rig, “but by the time I had driven the three miles to the Mission my clothing was so tightly iced my brother had to call for help to get me out of the buggy and into the house.”

Thomas continued making mission trips throughout his ministry, but from the beginning he emphasized recruiting and training native catechists to take up the work. He firmly believed Indian preachers were “a great deal more effective … among their own people than any white man could be.”

Riggs’ belief in the value of native ministers was ironic because he equated conversion with putting away their traditional ways. Men who wanted to preach the Gospel were expected to cut their hair and wear suits and ties; most adopted “white” names as well. A thornier issue for native catechists and converts in general was that of polygamy. When they became ministers Indian men had to discard all but one wife if they had more than one, as many did.

“Yellowhawk came out boldly [as a Christian],” Nina Riggs reported in a letter home. “He put away one wife and dresses like a white man.” Her rosy report veiled a painful reality for the Indian women involved. To make his choice easier, Yellowhawk pitted his two wives against each other, and vowed to keep the one who more completely mastered the white methods of cooking, washing and ironing.

Thomas Riggs never expressed any doubt that such pitiless treatment was warranted to achieve a greater good. The women who had to deal with being rejected, who went from positions of security and status to uncertain lives on the fringe of society, were part of a heathen past and impediments to their husbands’ salvation. They had to go. It was as simple as that.

Aside from spiritual considerations, Thomas Riggs believed that history’s tide was running against the Lakota: he was convinced they had to adapt and live as white men did in order to survive. He helped Indians file homestead claims, and worked to get them the cattle they were promised when they were “disarmed and dismounted” in the wake of Custer’s defeat in 1876. Riggs tried to teach by example as well. “Whatever [my father] did was primarily for the purpose of teaching the Dakotas — whether it was planting a field of oats or corn, or building a log house,” wrote Theodore. “He did it to show the natives how the work could be done and the purpose for which it was done.

|

| When the Riggs family's modest frame home burned down in 1898, Thomas replaced it with this magnificent structure of native stone, which took nearly three years to complete. |

In the winter of 1880-81, Lakota living along the Cheyenne and Moreau rivers organized a great buffalo hunt, which turned out to be the last of its kind. A party of about 60 hunters and 40 women gathered at Frederick Dupree’s Cheyenne River ranch on Thanksgiving. Thomas Riggs was the only white man among them.

After four weeks of slogging through heavy snow the party reached Slim Buttes, where they sighted buffalo on the day before Christmas. “There is nothing which changes the appearance of a human being quite like the expression on an Indian’s face when he starts to run and shoot buffalo,” recalled Riggs. “I have heard the Indians speak of it, but I never really understood until I saw it myself. They look fearful – like demons.”

Thomas participated in all phases of the hunt, even the ritual repast of raw meat. Another hunter “cut off a hunk of raw liver and passed it to me,” wrote Riggs. “I cut off as small a piece as I thought was respectable and put it in my mouth, but it was an awful job for me to chew and swallow it.”

After almost two months afield, Riggs took home seven robes and a greater appreciation of Lakota culture. “I was able to study their habits and language, to learn to think as an Indian and to understand his point of view,” he wrote. “I [also] learned the term ‘lazy Indian’ had no proper application.” Riggs was impressed by the diligent and “thoroughly professional” way the hunters and the women who processed the carcasses went about their work, which was so different from their approach to domestic chores in the settlements.

|

| Oahe Mission Chapel, next to the Riggs family home, was built in 1877 from a load of lumber delivered by legendary riverboat pilot Grant Marsh. When Lake Oahe flooded the site it was moved to Oahe Dam Visitors Center, where it stands today. |

In the course of ministering to his widespread outstations, Thomas Riggs often spent weeks at a time away from Oahe Mission. On one occasion tragedy struck while he was absent. The family’s log home burned to the ground on Nov. 26, 1898; no one was injured, but “everything made dear by long association” was lost. Thomas was able to indulge his architectural streak in the aftermath, at least. He designed a new, larger home built with stone from the surrounding pastures which endured until it was inundated by the waters of Lake Oahe in the 1950s.

Raising a family of his own while he was away so much would have been impossible without the unstinting hard work and support of a good wife. Thomas was among the luckiest of men for he was blessed with two such women in his life. Margaret Louisa Irvine came to Oahe Mission as a lay helper in the 1870s. She and Thomas worked together for many years, and after Nina’s death their relationship gradually deepened. They were married on the last day of March, 1885.

Louisa (as she was known) was warmly welcomed into the family fold by Theodore. “She was a remarkable person — highly educated, a gifted musician, deeply religious and wholeheartedly interested in mission work,” he wrote of his stepmother. “No boy could have had a more loving mother.”

Thomas and Louisa had four children together. Their two daughters both came to sorrowful ends: Cornelia died while an infant, and Muriel succumbed to rheumatic fever, the scourge of that era’s children. Lawrence went on to be a Rhodes scholar and teacher, Robert a mathematician and auditor.

Theodore’s education “was partly ‘home grown’ in the Wild West and partly in civilization,” as he put it. He lived with relatives and attended school back east, and spent his summers in Dakota. When he’d completed his education at Johns Hopkins Medical School and a surgical residency in New York, Theodore returned to South Dakota to practice. Pierre’s medical facilities were somewhat primitive in 1909, even by the standards of the day, and he set about changing that. Theodore played a leading role in recruiting physicians to town, and in time the Catholic Benedictine Sisters built St. Mary Hospital, a five-story, modern structure worthy of the state capital.

|

| Thomas Riggs' ideal for the Indian people was perfectly represented by these prim and well-scrubbed schoolgirls, who were attending classes in an environment that could hardly be more different from their parents' world. |

As Thomas advanced in age, maintaining the ranch and keeping up with his ministerial work became too much for him. Robert returned to help run the ranch in 1910 and brought the next generation with him.

Betty (Riggs) Gutch and her twin sister Jean “are 180 years old,” says Betty with a laugh: they were born in 1920, while the family lived in the big stone house at Oahe. They might have been delivered at home, as was common at the time, but because they were twins, Robert and his wife Florence decided it would be safer in the Pierre hospital.

Betty recalls her Grandpa Thomas saying grace before every meal and reading a chapter from the Bible after, and the many Indian friends who stopped by to see him. Beyond that, he spent most of his time upstairs or in his carpenter shop “because we made too much noise,” says Betty. Louisa tried to ride herd on the grandkids and keep them from causing too much chaos, but Robert eventually had to put up his own house nearby.

In 1919, after 47 years of missionary work, Thomas became, “keenly conscious of nearing the limit beyond which it was not safe nor wise to venture,” and he resigned his position. For the first time in more than 80 years, there was no Riggs in the active ministry.

After enjoying almost two more decades of relatively good health, Thomas suffered an incapacitating accident and began to fade. Theodore and his family went on a trip in the summer of 1940, and while they were gone Thomas began refusing food, taking only a little water. When Theodore returned he was shocked by how bad his father looked. “I might have given him intravenous fluids, but he looked straight at me and held up his hand, palm toward me,” wrote Theodore. “I understood.”

Within the hour, on July 6, 1940, Thomas Lawrence Riggs was dead. His earthly remains were laid in a wicker basket and buried next to Nina in the Oahe Mission’s family plot. His soul rose up to heaven, there to give an account of his life to the Lord he had served long and faithfully.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2010 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

I came upon the article accidentally as I was looking up background material while attending 'Winter Talk', an annual meeting of Indigenous people represented in the Episcopal Church. It is enlightening and disturbing to understand better the history of (mostly) well-intended missionaries and their white supremacist tendencies and practices and their lasting effects, good and bad. Winter talk is a way to help the Episcopal Church to come to terms with this. to listen, and within the church, to make amends. At least the Riggs mission learned and taught the Lakota language.