The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Following Black Elk’s Good Red Road

|

ONLY 11 AMERICANS have ever been canonized as Catholic saints. The 12th could be Nicholas Black Elk, a thoughtful and humble Lakota holy man who lived in the Pine Ridge country of southwest South Dakota in a tiny community called Manderson.

Black Elk is remembered as a tragic 19th century visionary who, in his old age, despaired the loss of his lands and culture. That much is true. However, Catholic leaders say he was also an exemplary Christian who preached and practiced hope and forgiveness. There are disagreements over which part of his life was most meaningful, but of course his latter years prompted the Catholic Church to consider him a saint.

His road to canonization, which began in 2017, could span decades. The same process took more than a century for Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th century Mohawk woman who was canonized in 2012. First, Black Elk must be declared venerable by the Vatican. Then religious leaders will look for miracles attributed to him. However, the very fact that he is a candidate for sainthood has already brought bishops, religious pilgrims and other visitors to Manderson and the Pine Ridge.

*****

MANDERSON HAS 400 residents and one store. That is one store more that it would have if not for Emma Clifford, who for 40 years has operated Pinky’s, a social spot for youth and adults. As Black Elk’s legacy grows with the prospect of sainthood, travelers from far away now occasionally share the counter.

|

| Sunday Mass welcomes worshippers at St. Agnes Church, which has become a centerpoint of the effort to canonize Black Elk. |

“We are seeing not only Catholics, but non-Catholics, people of all faiths,” Clifford says. “But that is the story of Black Elk. When we pray to him today, we pray for people of all other faiths, hoping they will respect us.”

The town’s only other private business is Bette’s Kitchen, run by Betty O’Rourke, a great-granddaughter of Black Elk. She and her extended family serve meals in their home to locals and out-of-towners. Some days, they host meetings or gatherings on the hilltop residence, with its expansive views of the chalk-white bluffs that give the Pine Ridge its name.

The family’s land, on the southern edge of town, is where Black Elk famously welcomed Nebraska writer John Neihardt, author of the book Black Elk Speaks that brought literary attention to both of them many years after it was published in 1933. A one-room log cabin where the holy man spent some of his final years stands beneath shade trees halfway up the hill.

The busiest place in Manderson is a tribal school, the smallest of nine on the Pine Ridge with 152 students. Every year on Oct. 8, as the faculty and staff observe Black Elk Day, they track how many of the students are direct descendants of the holy man. At last count, there were 28.

St. Agnes Catholic Church, where Black Elk preached and prayed for decades, stands on the north side of town. The white church is plain even by rural standards. Below eight simple stained-glass windows are two rows of rickety pews — the same wood pews, no doubt, where Black Elk once sat and kneeled.

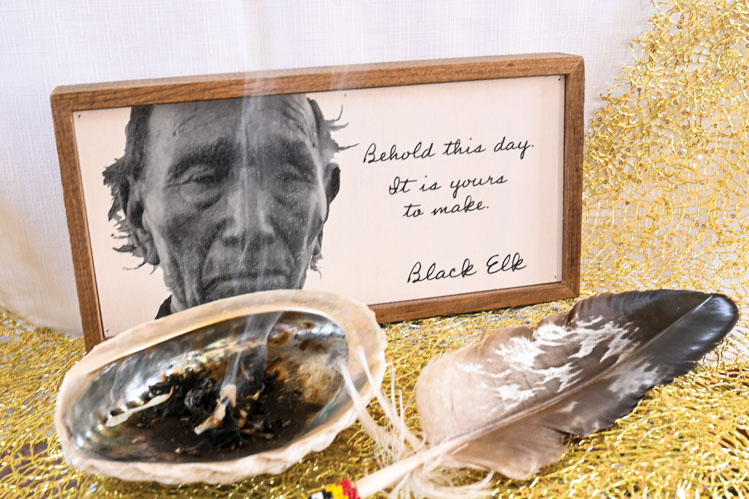

A brown tipi with a cross has been painted behind the altar. Statues of Mary and Joseph and a picture of Jesus stand at the front, but they share this church with Black Elk: his picture hangs above the sacristy door; prayer cards with his image lie in the pews; another photo of the Lakota holy man rests on a table with a sage bowl and an eagle feather; and just below the picture of Christ is a wood chair, colorfully painted by local artist Mark Anderson with Black Elk’s name and likeness.

*****

ON A WARM SUNDAY last summer, we departed Rapid City, turned left at Hermosa and drove two hours southeast, skirting the southern edge of the hauntingly beautiful Badlands country, to learn more about Manderson.

|

| Black Elk descendants are numerous in Pine Ridge country. Betty O'Rourke, a great-granddaughter, ran a restaurant in Manderson with help from her grandchildren, Austin and Maisena. Photos of the man who may one day be a saint decorated the dining room wall. |

When we arrived at 9 a.m., Betty O’Rourke and her family were busily preparing to serve a group of college-age missionaries who were scheduled to arrive for lunch. With her black hair drawn tightly back, you can see a resemblance between Betty and her famous great-grandfather, whose photos hang in the dining room of the restaurant and home.

“I was born a Black Elk,” she said, between checking casseroles in the oven. “My mother, Grace, was a Black Elk. They called her Gracie. My Aunt Kate was the first Native American woman in the U.S. Army.”

Betty says she and her husband, Chuck, are old enough to retire, but they keep running the restaurant for two reasons: the community needs an eatery and, “it teaches our grandchildren how to be in the world and run a business.”

She does not advertise or promote her connections to Black Elk. “Everything Grandpa said was that you should never profit from your culture,” she says. “We have certain people who do but I don’t think it’s right.”

Betty said she wouldn’t join us at Mass. She had to watch the casseroles. “When I was at Holy Rosary School, we would go to church every day. Sometimes two or three times a day, but you can’t get me to church today because I believe God is with me all the time. I don’t have to go to that building to pray to Him.”

She likes the priests from Holy Rosary, who often visit the restaurant. “They know how I feel and when they come here to eat, they don’t talk to me about going to church,” she laughs, and then she returns to the oven.

*****

MASS STARTS AT 11 a.m. on most Sundays. A priest and four Catholic nuns from the Holy Rosary Mission arrived just minutes beforehand because Joyce Tibbitts, the parish catechist, had already prepared the altar. Tibbitts does many duties that Black Elk performed for decades.

|

| The simple but sturdy wood-frame church at Manderson was built by Black Elk and his friends in 1911. |

The service began with Ave Maria, led by the nuns who had come from India to work as missionaries. One strummed a guitar. The church could hold a hundred people, but only a few dozen sat in the pews.

Father Edmund Yainao Lunghar, a priest from the Himalayan Mountain country in India, welcomed everyone with a smile. In a short homily, he told a story of a single mother who struggled to raise a troubled teenager. He said the woman steadfastly maintained that, “At the end of the day, no matter how much he misbehaves, he is still my son.”

Father Edmund asked, “How much greater is God’s love? How much will your heavenly Father forgive you if you turn to Him? Let us pray that we have a listening ear. The calling of the Good Shepherd, the whispers of the Good Shepherd, invites us to pastures where life is abundant.”

Midway through Mass, Tibbitts went from pew to pew, waving smoke from a bowl of smoldering sage toward each parishioner. It is a Native American version of the Catholic Church’s use of incense as ceremonial purification.

Rather than ring a bell, Tibbitts beat a drum as Father Edmund consecrated the bread and wine. A service at St. Agnes has the repetitive traditions of the Catholic Mass that bore the youth and comfort their elders, yet it is also like no other religious service in the world. During the Prayers to the Faithful, an appeal was made for a teen who had just died in a hit-and-run accident on the highway; another was said for a boy who was killed in a drive-by shooting that week.

One of the worshippers, a slender woman in her 50s, appeared to be intoxicated. During the Eucharistic prayers while everyone else was kneeling, she approached the altar. She’s not the first troubled person to do so at a Sunday service. It happens in other churches. But never was such a woman treated kindlier. Father Edmund gently assured her they could talk later. She returned to a pew.

At the close of Mass, the congregation recited a special Prayer for the Canonization of Nicholas Black Elk, which includes these lines:

Faithfully he walked the Sacred Red Road

And generously witnessed the Good News

Of our Lord Jesus Christ

Among the Native American people.

Open our hearts also to recognize

The Risen Christ in other cultures and peoples.

The congregation then stepped outside the old church building to socialize in an adjacent hall over coffee and baked goods. An artist’s drawings, featuring Black Elk with a halo, hang in the hall. Tibbitts says the art is considered inappropriate by the Church because halos are reserved for saints, and Black Elk is yet to be canonized.

*****

MANY SAINTS WERE imperfect early in life. Many suffered great injustices. Black Elk fits both categories.

He was born between 1858 and 1866. His tombstone in the weedy cemetery across the road from St. Agnes Church lists the former. The Catholic Church seems to have settled on the latter, while other historians cite 1863.

Black Elk nearly died when he was about 9 years old. He recounted the incident in great detail to Neihardt, whose daughter Hilda took copious notes for days and days during the summer of 1931. Her notes were published in Raymond DeMallie’s 1985 book The Sixth Grandfather. It’s considered more accurate than Black Elk Speaks, which is accepted as a more liberal translation embellished by John Neihardt’s own poetry and spirituality.

|

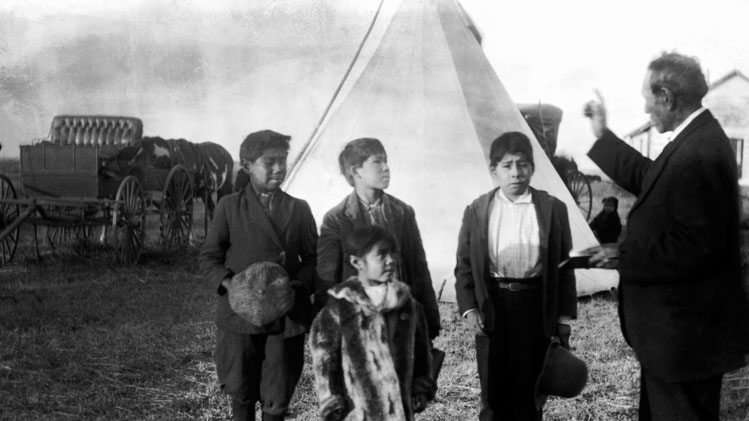

| Black Elk used the missionaries' Two Roads Map to teach children and adults about Christ's life. |

Black Elk recalled that his legs, arms and face became swollen and then he drifted into a dream state. He remembered being visited by grandfathers who instructed him in the good that comes from the harmonious red road and the evil that comes from the black road, including war and death. He realized that the sixth grandfather, a very old man with white hair, “was myself … at first he was an old man but he got younger and younger until he was a little boy nine years old.”

He saw a village of men, women and children who were dying. “I was frightened at the sight and tried to get away,” he said. “I passed in front of the tipi and all the people got up. The spirit said, ‘That’s the way you shall save men.’”

His recounting of the 12-day dream state took 22 pages in The Sixth Grandfather. Toward the end he notes, “They had taken me all over the world and showed me all the powers. They took me to the center of the earth and to the top of the peak they took me to review it all. I was to see the bad and the good. I was to see what is good for humans and what is not good for humans.”

*****

THREE YEARS LATER, Black Elk and his family were at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where Lt. Col. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry were annihilated by the Lakota. Black Elk, then 12, was kept away from the main battle but he had close encounters with soldiers. At one point he was urged by an adult warrior to scalp a dying soldier. The Neihardt notes record him remembering, “Probably it hurt him because he began to grind his teeth. After I did this I took my pistol and shot him in the forehead.”

As the fighting concluded, he and about six other boys returned to the battle scene. “When we got there some [soldiers] were still alive, kicking. Then many boys came. And we got our arrows out and put arrows into the men and pushed some of the arrows that were sticking out in further.”

He took another scalp and handed it to a younger boy. “Then I got tired of looking around,” he said. “I could smell nothing but blood and gunpowder, so I got sick of it pretty soon. I was a very happy boy. I wasn’t a bit sorry.”

However, in the winter of his 17th year he felt a calling. He told the Neihardts that he heard a voice saying, “Your grandfather told you to do these things. It is time for you to do them.” He developed a horse dance. “After this ceremony was completed it seemed that I was above the earth and I did not touch the earth. I felt very happy and I was also happy to see my people, as it looked like they were renewed and happy. They all greeted me and were very generous to me, telling me that their relatives here and there were sick and were cured in a mysterious way and congratulated me, giving me gifts. I was now recognized as a medicine man at the age of 17.”

|

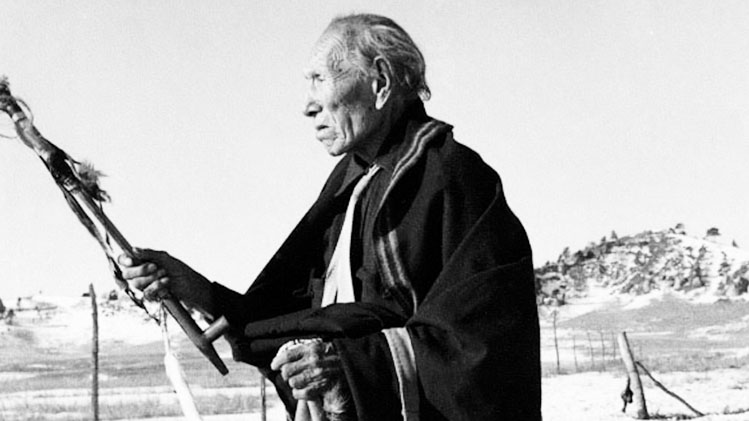

| "He prayed with a pipe and a rosary," says Father Daoust of Holy Rosary. |

In 1886 he learned that Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show wanted to employ Indians to journey “across the great water” to Europe. He and about 10 friends joined, traveling by train to New York City where they entertained at Madison Square Garden for months.

“As we left New York I could see nothing but water, water, water,” he told the Neihardts. He performed for Queen Victoria in England, and later quoted her as saying that it was wrong for white people “to take you around as beasts to show to the people.”

He and three others became separated from Buffalo Bill’s entourage and found themselves lost in a strange country. None could speak English. Fortunately, London authorities linked them with another traveling show run by a man called Mexican Joe. They toured Italy and France for another year before returning home.

Back at Pine Ridge, he found his relatives and friends confined within reservation borders. Some were ill with strange diseases introduced by settlers and soldiers. Many were hungry and starving due to the demise of the buffalo culture and broken promises. Federal rules titled “The Code of Indian Offences” outlawed traditional dances and religious ceremonies. The rules also limited the practices of medicine men like Black Elk.

A new spirituality called the Ghost Dance was gaining strength. Black Elk heard that friends were dancing it below Manderson at Wounded Knee so he went to observe. “They had a sacred pole in the center,” he told the Neihardts. “It was a circle in which they were dancing and I could clearly see that this was my sacred hoop and in the center they had an exact duplicate of my tree that never blooms and it came to my mind that perhaps with this power the tree would bloom and the people would get into the sacred hoop again.”

The Ghost Dance’s popularity scared U.S. military leaders, and that led to Sitting Bull’s violent death on Dec. 15, 1890. It also contributed to the tragic confrontation between cavalry soldiers and the Lakota at Wounded Knee Creek on the morning of December 29.

Black Elk had spent a sleepless night because he sensed something was about to happen. He was walking at daybreak when he heard gunfire. From afar, Black Elk and a friend saw the wasicus (white men) coming with wagon guns. They heard shooting and cries. They saw women and children running to hide in the gullies. He and about 20 others rode to help. A bullet grazed his leg. He told Neihardt that he felt bulletproof, and that he heard bullets whizzing by.

In Black Elk Speaks, the holy man is quoted as saying that something died in the blood and mud and was buried in the blizzard that followed. “A people’s dream died there,” Neihardt wrote. “It was a beautiful dream … the nation’s hoop is broken and scattered. There is no center any longer, and the sacred tree is dead.”

That tragic poetry is not found in the actual notes, as published in The Sixth Grandfather. In DeMallie’s text, Black Elk describes the massacre and the aftermath. He laments that perhaps he should have died with the many others, and he says he prayed to the spirits above, saying, “Grandfathers, behold me and send me a power for revenge.”

*****

THIS IS WHERE Black Elk’s life story gets even more complicated. After the Wounded Knee massacre, he continued to serve his people as a medicine man. On many occasions, he found himself at sickbeds with Christian missionaries who were also there to serve. He had friends who had converted to Christianity. In fact, his first wife, Katherine War Bonnet, was a Catholic. She died in 1903.

|

| This photo of Black Elk introducing the rosary to a Lakota child was widely used in Holy Rosary's promotional materials in the 1940s. |

In the autumn of 1904, he was tending to a sick boy who lived north of Holy Rosary when Father Joseph Lindebner arrived. The Jesuit priest, a native of Germany, was well-liked by many reservation residents, who called him “the Little Father.” Lindebner had baptized the lad earlier, and reportedly became upset that Black Elk was there with his tobacco offerings, drums, rattles and other items.

“Satan, get out!” Lindebner declared, tossing Black Elk’s belongings out of the tent. At least, that was the story told decades later by Black Elk’s daughter Lucy. She said her father did not return the anger. The priest obviously saw something special in the medicine man and invited him to accompany him back to Holy Rosary to learn more about Jesus Christ.

Black Elk, curious about the new religion, stayed two weeks at the mission. He found Catholic theology compatible with his traditional beliefs in the Great Spirit, wakan tanka, and on Dec. 6, 1904 he was baptized. It was the feast day of St. Nicholas, so he took the saint’s name.

The rest of Black Elk’s story is the era not covered in Neihardt’s Black Elk Speaks. He converted hundreds of people. He and his friends built the St. Agnes Church building that stands today. He traveled, sometimes long distances by horseback in stormy weather, to tend to the sick and dying. He served short assignments at St. Stephen’s Mission in Wyoming and Marty Mission on the Yankton Sioux Reservation, but most of his life was spent serving the Pine Ridge people.

Bill White, a descendant by marriage to Black Elk, is a member of the Sainthood Working Group. White is a permanent deacon of the Catholic Diocese, serving at Porcupine on the Pine Ridge. He believes Black Elk became comfortable with Christianity because it fit his childhood vision of unity among men. “He saw the same thing written in Revelation. We are all standing before the Lamb of God. He always was striving to unite people. He had many non-Native friends throughout his life.

“I am certain he fits the model of a man who lived a heroic life and a model life,” White says. “He remained fully Lakota, and he saw that as being compatible with Christianity.”

*****

“BLACK ELK IS MY hero,” Joyce Tibbitts told us, as her congregation departed the church social hall on that Sunday morning. Actually, there are two halls behind St. Agnes Church — a Tekakwitha Hall, where Native American women once met in prayer groups, and a Black Elk Hall for the men. Today, Tekakwitha Hall is Tibbitts’ parish office, and a repository of information for the sainthood effort.

Tibbitts says the process began when relatives of Black Elk, who had attended the canonization service for Tekakwitha in 2012, asked Robert Gruss, then the bishop of the West River Diocese, if their grandfather might also deserve consideration. The working group was created, and it has already submitted a request to the Vatican Congregation of Saints.

|

| Joyce Tibbetts' tattooed arms reflect both Christian and traditional Lakota spirituality. Her pastoral duties at St. Agnes Church are akin to those performed by Black Elk in the early decades of the 20th century. |

Though there are 10,000 saints, none are quite like Black Elk. “He prayed with both a pipe and a rosary,” says Father Joe Daoust, the superior of Holy Rosary Mission and a member of the group. “Some say he walked the two roads between Lakota and Catholic spirituality,” Daoust says. “But he actually blended the two into one red road to God.”

Tibbitts says she and others now walk that same road. “We are a swirl of religions — traditionalists, Christians and combinations of the two. We go to church and we also go to the sweat lodge or the big sun dance in summer.”

She says priests from Holy Rosary once distributed Holy Communion at the sun dance, but the practice was stopped — not by Catholic clergy but by traditional Native American leaders. “If a priest does show up at the sun dance today, the people will be respectful, but they cannot participate anymore.”

Tibbitts believes the challenges of everyday life on the reservation demand that anyone who wants to help — Christian or traditional — must be welcomed. “We’ve once again had a string of suicides,” she said. “The youngest was just 11, the oldest 18. We had a boy hit by a car. This week we buried a 20-year-old who died from illegal booze.”

Because liquor and beer sales are prohibited on the Pine Ridge, bootleggers are making home brews known as skips. “They use everything from hand sanitizers to rubbing alcohol, anything with an alcohol content,” Tibbitts says. “The result is a toxic brew that is killing our people.”

Poverty and health crises further complicate life in Manderson and the surrounding communities. Premature deaths are so frequent that plans are being considered to expand the parish cemetery, which lies just across the highway from St. Agnes Church.

Cynics might surmise that neither Native or Christian spiritualities have done enough to change a sad trajectory that has persisted since the buffalo were nearly exterminated and reservation borders were drawn. Optimists, on the other hand, would find hope among the good people who run the restaurants, stores, schools and churches of Black Elk’s home territory.

When Black Elk and Neihardt climbed Harney Peak (now known as Black Elk Peak) in 1931, the holy man spoke of the troubled times that faced his people. “The good road and the road of difficulties you have made to cross,” he said that day, “and where they cross, the place is holy.”

Seven decades after Black Elk’s death, it’s still easy to encounter holiness in his hometown. Sainthood might someday bring greater attention to the holy man’s humble, forgiving legacy. Maybe it would even bring about miraculous change.

However, the people we met in Manderson are not waiting for miracles. Like their town’s famous native son, they face the intersecting roads of good and bad every day. “I could see that it was next to impossible,” Black Elk said of his vision for a great flowering tree of unity in 1931, “but there was nothing like trying.”

Perhaps the beautiful miracle is that the trying continues today.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the November/December 2022 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

having grown up in the sierra nevada mountains near rservations by yosemite i learned at 10 years of age ( i am 84 now ) from my adopted mother that i was irish and cherokee. i grew up having jet black hair and a dark complexion. the local indians assumed i was just another indian kid.i experienced several times the attitudes of the white people toward me. as i grew older i studied history and came to realize the horrible prejudice that took place toward the indian nations. in many places it still exists today. the alcohol still being soldat rez border stores run by whites at such places as pine ridge, cheyene river, osage, crow, navaho and others is discusting today to say yhe least. to bad it can"t be stopped!

ll