The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

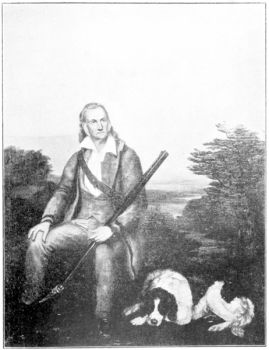

Audubon’s Dakota

Apr 8, 2014

John James Audubon’s expedition up the Missouri River proved to be his last. America’s pre-eminent naturalist wanted to gather material for a new book on Plains mammals, so in April 1843, at age 58, he boarded the American Fur Company’s steamship Omega at St. Louis with about 100 hunters and trappers and embarked for Fort Union, near the present-day Montana-North Dakota border. Audubon kept a detailed journal, giving us a rare look at life in the Missouri River Valley 40 years after Lewis and Clark.

The valley had changed considerably since Lewis and Clark’s voyage. Several trading posts and military forts dotted the river, and some semblance of law was being enforced. Audubon’s party nearly ran into trouble as they approached the mouth of the Big Sioux River on May 13. Prohibition was in place, and soldiers were required to inspect passing boats for illegal liquor. Audubon had written permission from the federal government to transport liquor, but the traders and trappers aboard did not. He wanted to help, so he launched a clever ruse to delay the inspection while the crew stashed the bottles into the dark, deep recesses of the ship.

Audubon asked to visit an officer stationed at a fort about 4 miles away. The officer, honored at the chance to receive Audubon, took the explorer on a two-hour wildlife tour. It gave the Omega’s crew plenty of time to hide the liquor, which went unnoticed during inspection.

Audubon’s aim was explore wildlife, and he found an amazing diversity of plants and animals that are no longer found here. Just beyond the Big Sioux, the party spotted a black bear swimming in the river. “It caused a commotion,” Audubon recorded. “Some ran for their rifles, and several shots were fired, some of which almost touched Bruin; but he kept on, and swam very fast. Bell shot at it with large shot and must have touched it. When it reached the shore, it tried several times to climb

Further upriver Audubon first sighted the Western Meadowlark, “whose songs and single notes are quite different from those of the Eastern States. We have not yet been able to kill one to decide if new or not.” They also saw the Burnt Hills near Chamberlain and Platte.

Perhaps the most disheartening portion of the trip is the vast buffalo slaughter Audubon witnessed and in which his party became involved. By the 1830s, the American Fur Company had a string of posts along the river, and buffalo hides were in high demand. On May 18, 1843, Audubon met four barges heading downriver from Fort Pierre loaded with 10,000 buffalo robes. “The men live entirely on Buffalo meat and pemmican,” Audubon wrote. “They told us that about a hundred miles above us the Buffalo were by thousands, that the prairies were covered with dead calves, and the shores lined with dead of all sorts.”

Hardly a day passed that Audubon did not see a dead buffalo floating past, or carcasses dotting the prairie. On May 23, several of his companions embarked upon a buffalo hunt. The men killed four animals. “Only a few pieces from a young bull, and its tongue, were brought on board, most of the men being too lazy, or too far off, to cut out even the tongues of the others; and thus it is that thousands multiplied by thousands of Buffaloes are murdered in senseless play, and their enormous carcasses are suffered to be the prey of the Wolf, the Raven and the Buzzard,” Audubon lamented.

The naturalist continued exploring, recording and sketching through the summer. He claimed to have discovered at least 14 new species of birds and three or four new mammals. Many of his observations became the basis for his book, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–54). But with today’s concrete dams, sprawling reservoirs and greatly diminished diversity of wildlife, the Missouri River Valley hardly resembles the region Audubon explored 171 years ago.

Comments