The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Painting the Trophies

|

| The Hatterscheidt trophy room has evolved at the Dacotah Prairie Museum, says curator Marianne Marttila-Klipfel (left). With her are the artists who painted the scenes: Lora Schaunaman (center) and Debra Many Carson. |

“This traveling circus of ours lives off the country,” wrote Aberdeen safari hunter Fred Hatterscheidt. “We shoot to eat. We hunt for pleasure. We kill for trophies.”

Few South Dakotans ever hunted the world with the passion of Hatterscheidt, or left the public his guns, journals and taxidermy mounts. However, the staff and board of Dacotah Prairie Museum in Aberdeen soon grew uncomfortable with the collection that they inherited when the hunter bequeathed it to them along with a three-story building that became the museum in 1970.

“The mounts had to be displayed,” says Lora Schaunaman, a retired curator of exhibits. That was part of the agreement Hatterscheidt made with the board even though the lions, tigers and other exotic species hardly fit the museum’s mission of exploring northern South Dakota history.

Perceptions of safaris have also changed since Hatterscheidt died in 1973. When he was circling the globe in the 1950s and 1960s, trophy hunting was accepted as the sport of wealthy adventurers. Ernest Hemingway, one of the most famous American novelists of the 20th century, wrote extensively about his African excursions.

Other celebrities also popularized safari hunts. Teddy Roosevelt, the 26th president who is remembered as a conservationist, embarked on an African safari soon after leaving the White House in 1910. He later bragged that he’d killed 296 animals, including nine lions and 15 zebras. John Wayne roped a 450-pound wildebeest while filming Hatari, a 1962 movie about hunters who captured wild animals for zoos.

Even as those famous hunts were occurring, some game species were nearing extinction. Also, the concept of safari hunting became entangled with the colonialism that exploited native peoples in African countries. The stereotype of the rich American or European flying to an impoverished Third World village to kill for sport was reenforced when a Minnesota dentist shot a beloved lion named Cecil that lived in a national park in Zimbabwe.

However, the staff of the Aberdeen museum had recognized the dilemma long before Cecil’s death in 2015. A 1990 museum report recommended that Hatterscheidt’s gun collection be removed because it gave the appearance of “promotion of big game hunting.” The report, titled “A Man of His Times,” noted that the museum benefactor lived and hunted at a time when sensibilities were quite different.

Even for his own time, Fred Hatterscheidt was unique. He was born in Cologne, Germany in 1893 and came to America as a child with his parents, who were looking for an opportunity to farm. They arrived in Aberdeen when he was 10.

|

| Hatterscheidt was with Frank Scepaniak in Siberia when Scepaniak killed the polar bear, which was mounted in full. |

He studied at the Aberdeen Business College and Northern Normal (today’s Northern State University). He joined the South Dakota National Guard in 1914, the same year he went to work for a local real estate firm.

Hatterscheidt married Ruth Kimble in 1922. They did not have children, but they embraced the greater Aberdeen community. Today, their Hatterscheidt Foundation continues to provide scholarships to students in the region. Hatterscheidt immersed himself in business and 30 years later the son of immigrants had the wherewithal to travel the world. Ruth accompanied him on a few of his trips. She collected fans. Her husband collected animal trophies.

Hatterscheidt kept detailed journals as he traveled. Like the taxidermy mounts, his thoughts and writings deserve to be judged in the context of the era. He wrote honestly and bluntly, at times questioning the customs of other cultures and in other instances, seeking understanding.

In September of 1952 he was hunting giraffe in the Tana Forest of Kenya. “We followed the wounded animal for miles and miles over mountain and desert,” he wrote. “We had to quit on account of the darkness and we were still ten or twelve miles from Camp.”

He continued on September 19: “Six boys tracking the animal over mountains and desert, and finally we had to give up spoor. We located four Giraffe feeding. We circled and came in against the wind. Smith designated the kill, and Bob, our gun boys and I, dropped out of the hunting truck which went on the prescribed 200 yards. I got in the first shot with the .416. Bob used his 30.06 immediately after. The heavy impact of the .416 knocked the Giraffe clean off his feet. He jumped up and ran after the herd. Bob shot five times and registered three hits, but the bullets were flattened out under the skin which is nearly one-half inch thick. I got in another shot with the .416 and this slowed up the Giraffe to where Captain Smith headed him off near the road. The animal was about 16 or 18 feet tall and weighed nearly two tons. It was all our truck could do to pull and turn him over.”

On Sept. 29, 1952, he related an elephant kill. “Trailed Elephant for an hour or two (time means nothing in the African jungle). Elephant Camp on the Tana River. This was the highlight of our trip. Killed a six ton or more (7 tons) Elephant over 100 years old and carried 160 pounds of ivory (figuring both tusks). I fired three shots from the .416; the first one to the heart. He ran less than 20 yards and fell dead. Captain Smith stood silent in reverence to the dying giant of the Tana Forest. Tears ran from the Elephant’s eyes and perspiration formed in pools on his head.”

He also observed foreign commerce, noting in England on August 11, 1952, “There are men in charge of business who know nothing about it. They don’t even know what assets they have.”

A few days later he penned, “Sixty-eight colored natives were arrested in Johannesburg today.” It is one of several brief references to native Africans’ rebellions against apartheid and other injustices.

On the 1952 trip, he saw Hollywood movie star Spencer Tracy in a hotel lobby. “He is shorter than I, and his nose and cheeks are pot-marked,” wrote Hatterscheidt. “He is very homely and looked more like a tramp.”

In a 1959 trip to India, he scolded the leaders. “These ‘holier than thou’ politicians are no different than the Caesars of Rome as far as the masses are concerned. They wouldn’t let Bob and I walk on a street leading to the Palace of the President, nor take any pictures of Nehru’s palace. The people of India have never seen pictures of these in any newspapers. Nehru is always shown with (Hindu fashion) folded hands in greeting. Gandhi set an example of poverty but like our priests and ministers, those in power don’t follow Christ or Gandhi.”

He was more impressed with the rural people. “Bob and I have really experienced the life of an Indian Maharaja who used to have the exclusive right to kill a tiger. We have been waited on. We have been blessed and anointed with oil and sprinkled with rice, and a mark was put on my forehead. All good Hindus, especially the women, carry a red or black spot on their forehead. We were honored time and time again for being killers of the tiger, also their god. I can’t understand any of it.”

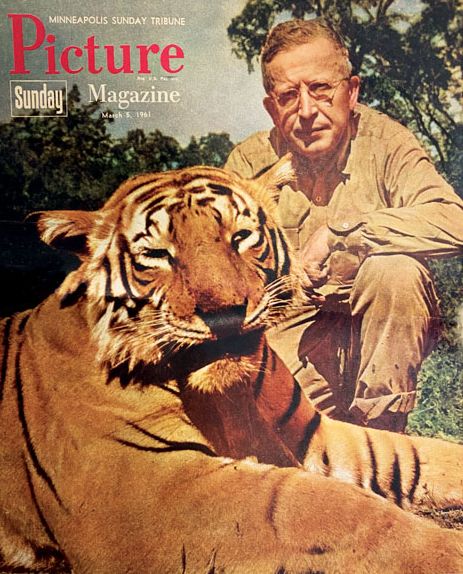

|

| Aberdeen hunter Fred Hatterscheidt made the cover of a Minneapolis magazine in 1961. |

Hatterscheidt welcomed publicity. In 1960, he offered his diaries to Farm Journal but the editor, Carroll Streeter, replied, “we are so terrifically crowded for space right now that I think it quite unlikely that we could.”

Regional newspapers were more receptive. In the museum files are several stories, including a 1959 account in the Aberdeen American News of a tiger hunt. “The Jeep lurched to a stop and as Hatterscheidt stepped down, the tiger was charging down on them,” wrote Sally Ross. “Hatterscheidt fired, but the tiger kept coming. Hatterscheidt fired again and again until the tiger reared on its hind feet and in one last roar, fell over backwards 20 feet away from the hunter.”

He told the Watertown Public Opinion that the 3,000-pound gaur he shot “represents a possible record kill.” He said it measured 6 feet, 1 inch at the shoulders — 2 inches higher than the previously recognized record.

On March 5, 1961, the Aberdeen hunter was featured on the cover of the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune Magazine with a trophy Bengal tiger shot in India. He said the tiger was, “bagged by means of a beat, where natives form a huge circle and drive the animals forward,” while he waited in a blind, 16 feet above the ground.

His trophy kills were preserved by some of America’s best taxidermists in Chicago, Houston and Seattle. Once mounted, they were shipped to W.H. Over Museum in Vermillion, the oldest museum in South Dakota. Someone there had apparently assisted Hatterscheidt in gaining permission for some of the hunts.

However, in 1970 two of Hatterscheidt’s friends stopped at the Vermillion museum to see the trophies and were chagrined to discover that the heads were in storage and not available to the public. At that very time, historians in Aberdeen were looking for a permanent home for the Dacotah Prairie Museum.

Hatterscheidt and two partners, Herman Pickus and P.A. Bradbury, agreed to donate the historic, three-story Western Union Building on Main Street in 1970. However, the offer included a stipulation that the museum shall exhibit the wildlife collection — including the aforementioned gaur and elephant.

Hatterscheidt died three years later, long before museumgoers began to balk at the mounted heads. However, by the 1990s, sensibilities were changing and the mounts, some now 40 years old, were aging. To make matters worse, the trophies were only separated from visitors by a rope, so some people were handling the mounts; bratty children were even pulling the whiskers from a leopard.

Schaunaman, an artist and art teacher, was then a curator. “The original exhibit was a trophy room with just the heads hanging on the walls,” she says. “It told the safari story of one Aberdeen businessman, but the reaction wasn’t always great. I didn’t even like to go in the room. People would bring their little kids and they would be afraid. Sometimes they would cry and scream. Our director back then was Sue Gates. She knew I didn’t like the room, yet we all knew the trophies had to be displayed. That’s when we came up with an idea.”

Sherri Rawstern, the museum’s longtime curator of education, urged her fellow staffers to consider two goals: show the animals in their native habitat, and do it in a manner that was more lifelike. That was the genesis of a major undertaking.

Schaunaman immediately reached out to Debra Many Carson, an Aberdeen wildlife artist. “I called her and said, ‘Have you ever painted an animal life-size?’”

|

| Buster the Bison has long been the mascot of the Dacotah Prairie Museum, but he became even more popular when artist Debra Many Carson painted a body to match his fuzzy head. |

The two women began by researching habitats and drawing sketches, which were later enlarged to fit the walls. They especially worked on the proportion of the actual heads to the painted bodies. Along with the art scenes, they incorporated real tufts of grass, soils, branches and a massive tree trunk.

Schaunaman tried to contact the original taxidermists, hoping to learn how to clean the mounts. Chris Klineburger of Seattle was deceased, but she was able to reach his son, Kent, who had continued in his father’s footsteps. “I only expected to get some advice, but when he heard what we were doing he insisted on coming to help,” she says. “He was on his honeymoon, actually. He came with his new bride, and she helped as well. They were here for about a week.”

During the 18-month transformation of the trophy room, museum staff also embarked on a major restoration of the handsome 1888 building that Hatterscheidt and his partners had given to them. Replacing the huge windows was an important part of the renovation.

“As they were taking out the big windows on street level, Sue Gates told us, ‘here’s your chance!’” Schaunaman remembers. “The window holes made it possible for us to get the big mounts outdoors for cleaning. Somewhere there’s a picture of me, standing on a step ladder and vacuuming a polar bear on Aberdeen’s Main Street.”

Other repairs were more subtle. Many Carson, the wildlife artist, had pet cats. “When I realized the leopard’s whiskers were missing, I watched for my cats to shed their whiskers and I saved them and glued them on the leopard,” she says.

A golden eagle, mounted on a rock, was especially difficult. “We had a terrible time getting him off the rock without breaking his talons,” says Many Carson.

The elephant head was also challenging. “They didn’t have the foam plastic models in those days, so it is framed with 2-by-4s and other heavy wood,” Schaunaman says. “The tusks are fiberglass, but they are heavy as well. We had to consult a structural engineer to see if the wall would hold it. We drilled through three layers of brick to the outside wall and bolted the mount to a steel plate.”

Using large chunks of material from Benchmark Foam in Watertown, they also sculpted two front legs for the gigantic elephant.

Though the murals span the continents of Earth, they blend together as if you were circling the globe on a jet plane. “It begins with sunrise of the Arctic, and then morning over the Rockies, noonday on the Great Plains, afternoon in Africa, a sunset in India and nighttime in the Himalayas,” says Schaunaman.

Many Carson and Schaunaman have slightly different styles, but their work blended perfectly. A casual observer might think it was all accomplished by a single artist.

Reaction from the public was immediately positive. “It changed by leaps and bounds,” Schaunaman says. And that has continued, even though public perceptions of big-game hunting are still evolving.

Marianne Marttila-Klipfel, who now serves as curator of exhibits at Dacotah Prairie Museum, says the safari murals and mounts have stood the test of time. “Now, with improvements made by Lora and Debra, the room tells a story in an educational context. The animals were placed back into their natural habitats and through artistic magic, life was brought to the exhibit. The rest of us get to benefit from their vision and talent.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments