The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

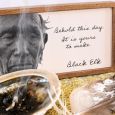

Pilgrimage for the Soul

|

| Lex Talamo became immersed in Lakota culture as she spent several years teaching writing to middle schoolers on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. |

I was 22 when I struck out from my home in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, for the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, teaching license in hand. My assignment seemed simple: teach 80 Lakota middle school students how to love writing, and to write well.

Pine Ridge, among the poorest places in the United States, soon assailed me with unanticipated problems. Many of my students’ home lives were marred by violence, poverty and abuse, which often resulted in unruly classroom behavior. My isolation, two hours from Rapid City, led to many “dark nights of the soul” that threatened to swallow me. I had fallen into a slump of dreading the mornings, the days, the rest of my life, and I didn’t know how to refocus my energy.

One afternoon, the Lakota Studies teacher wheeled his squeaky cart, complete with feathered rod and buffalo skull, into my classroom. His lesson was about the seven sites he said were sacred to the Lakota. “There is still power for our people in those places,” he told the students. “That is why our people still make pilgrimages, to this very day, to reconnect with the Great Spirit and pray for healing.”

I copied the list: Wind Cave, Sylvan Lake, Black Elk Peak, Bear Butte, the Badlands, the Black Hills and Devil’s Tower. I promised myself I would visit them all.

***

I decided that Wind Cave — the origin place of the Buffalo People, according to Lakota legend — would be the perfect place to start. The 115-mile trip would take me about two hours from the village where I taught. I spotted only a handful of cars as I followed Highway 18 west through a land of windswept beauty that left me dazed. Tawny prairie dogs barked and bustled around their colonies and several majestic buffalo grazed nearby as I arrived in Wind Cave National Park.

|

| Bison, the noble beasts at the core of Lakota culture and once on the verge of extinction, still dot the West River landscape. |

I signed up for a cave tour, which our guide began by recounting the story of Alvin McDonald, an eccentric teenager who moved with his family to the area in 1890. He had trouble making friends, so he sought sanctuary within the cave’s uncharted depths. Our guide flipped a switch in the large room, plunging the space into absolute darkness. “Think about that,” she said. “Think about exploring this cave, with its sudden drop offs, by yourself, and with only a candle for light.” She flipped the switch again, illuminating the water dripping off cave formations and cratered walls.

McDonald rolled out string as he explored so he could find his way around the cave, she continued. He left little puzzles — strings of letters — along the cave’s walls with the candle’s flame. Our guide showed us sooty markings on the cave ceiling, and then beamed her light into a crevice in the rock wall. “But my favorite story about Alvin involves this room and this passage,” she said. “If you’ll look toward my light, you’ll see a rare and beautiful crystal formation. Alvin knew there was a passage behind this, but to get there, he would have to destroy the crystal. He chose to leave the passage unknown, and the crystal intact, out of his respect for his cave.”

After the tour, I found McDonald’s grave, marked by a bronze plaque, near the natural entrance to Wind Cave. A Native American proverb popped into my mind: “Give thanks for unexpected blessings on their way.” McDonald’s story had sparked something in me, made me feel alive and reminded me that every day could hold unexpected blessings, as long as I showed up.

***

My next pilgrimage took me to Black Elk Peak, the sacred mountain where the Lakota welcomed the Thunder Beings each spring. KILI radio, the single station my car picked up, blared from my stereo as I tore down Highway 44. The road to Sylvan Lake, from which I could access the mountain trailhead, meandered through such tight turns above sheer rock precipices that my palms were sweaty and white. I reminded myself of what Reagan, my teacher friend on the Rosebud Reservation, had written to me once: “The hard stuff is always the good stuff. The hard stuff is what makes the story.”

|

| Prayer flags adorn tree branches near the summit of Black Elk Peak. Photo by Paul Horsted |

Halfway around the lake (really a manmade dam), I found a trailhead leading to Black Elk Peak and veered off the paved path. The way was steep and rocky, with giant metal handrails posted in one haphazard section of boulders. Jumping from craggy rock faces to the trail below, I felt like a child. I felt free. Unhindered. The sunlight on my face, which I missed so often due to the long hours I put in at school, invigorated my spirit. The solitude of the trail also strengthened me; I passed only a few people on my ascent.

I reached a point where the dirt path led to a wash of tangled woods; when I retraced my steps, I could not find the trail. I was still lost when the sun set and the temperature dropped. I found a cave-like crawlspace under an outcropping of rock. It was at least 10 degrees warmer inside than out, so I crawled in. I listened to the wind shriek past my sanctuary. I resolved to sleep if I could.

The sun’s rays peeked into my cave at dawn the next morning. I crawled from the space and tried to find the trail. Hours passed. Miles passed. When the sun shone directly overhead, hot and heavy in the sky, I abandoned all efforts to find a path. I picked a direction and ran. I did not stop until I heard the sound of a highway. I burst from the woods and found myself on an endless stretch of asphalt that gave no clue as to my location. No signs. No cars. No people. Then, a red sedan. I stayed by the side of the road, waving my arms above my head in distress. The car sped up and rushed past me.

I had no watch, no phone and I was out of water. I am going to die out here, I thought. Then a white minivan appeared on the horizon, making slow but steady progress down the hill. I prayed there were nice people inside. Then I stepped into the center of the road, waving my arms wildly. This time, the vehicle slowed and stopped.

I knew I must look crazy. My arms were scratched and bleeding from my crazed run through the woods. I had bits of leaf litter and twigs in my hair. I kept my hands loose and visible by my sides as I approached the minivan.

“Hello,” I tried, when the driver’s side window rolled down an inch. My voice came out choked and scratchy. I tried again. “I was hiking and I got lost …” My voice cracked. I took a step back, wanting to show that I was harmless, terrified he or she would leave me. “I was hoping you could point me in the right direction,” I said. “I’ve been wandering for the last 14 hours. I had to spend the night on the mountain.”

The window rolled down to reveal a pale-skinned couple in the upper bounds of middle age. “You poor thing,” the woman said. She sounded British. “You must be frozen. It was 34 degrees last night.”

|

| Arriving at Sylvan Lake proved to be a turning point in Talamo's pilgrimage. |

I waited while the British gentleman searched for Sylvan Lake in his phone’s GPS. “It’s that way,” he said, pointing down the hill. I asked how far. He said, “Thirteen miles.” I started crying. The woman twisted in her seat and started clearing out the back of the minivan. “Get in,” she said. “We’ll give you a ride.”

The man got out of the driver’s seat and opened the door for me. I slipped inside, babbling my thanks. “I promise I’m not a serial killer,” I said. They laughed; the man assured me they were not serial killers, either, “just an old British couple eager to see the great United States of America.”

They seemed at ease with me. They were also chatty. They asked what I did for a living. I told them I worked as a teacher in a reservation school. They showed genuine interest. “How is that?” the man asked.

“It’s hard,” I said. The woman asked how I coped, if I believed in God. I told the woman I did not know. “God is my answer to just about everything,” she said. “I trust that the people He puts in my way will be the ones I am supposed to meet and learn from.”

About 5 miles later, the Silver Bullet came into view. “There!” I shouted, way too loud. “That’s my car!” The man pulled into a parking spot near mine. They refused money when I offered. The man thanked me for “adding some excitement” to their lives. The woman said, softly, “I can’t wait to tell our friends that we picked up a hitchhiker.”

I waved as they drove off and thought, too late, that I had not asked for their names. I turned and looked out over Sylvan Lake.

The pilgrimage’s mission was accomplished. I had never been so glad to be alive.

***

In November, temperatures plunged. I knew I had only a short amount of time left to explore before blizzards, with their shrieking winds and bone-chilling cold, ravaged the state. After Sylvan Lake, I was terrified of getting lost while hiking by myself. But I wanted to continue my journey.

I took my scathed soul to the Badlands. The sky was a wet, watercolor blue, in sharp contrast to the sand-colored rocks and white cliffs I passed on the way into a parking lot by an overlook. The rest of the parking spots were empty.

I chose Notch Trail, the shortest of three trails detailed on a brown sign. The trail led to a breathtaking vista — layers upon layers of striated rock, sharp angles, peaks like steeples stretching out to specks on the horizon. I found a rock crevice that cradled my body perfectly. I sat down. I put my palms flat against the rock. I closed my eyes. I felt the increased pulse of my heart, and through my hands, the heartbeat of the earth. I felt the strength of the land lace up my palms, through my body. When I opened my eyes, the world seemed three shades brighter.

|

| The Badlands hold significance for the Lakota and several other indigenous tribes. Photo by Paul Horsted |

“Thank you,” I told the winds, the earth, and whatever might be listening.

I walked back to my car, believing I had completed a successful hike. Then the wind blew, so fiercely that it turned me around toward an exhibit sign that declared, “The Baddest of the Badlands.” I spotted the first trail marker, a stubby yellow pole about a foot high just beyond the sign, and I felt a hunger so sharp and fierce it surprised me. I wanted the challenge. I started forward.

Mushroom-like formations sprouted from a sea of craggy rock. I felt alive, following this trail across the beautiful land of extremes. My walk became a symbolic act of spirit. I was not sure where I was going or how much farther I had to go, but I was willing to take the journey. Going one step at a time, I reached the final yellow marker, identifiable by a corresponding red stripe at the top. Another canyon vista stretched out to the horizon. Below, the rock dropped steeply away, leaving me dizzy from the height.

I stood on the precipice, lost in the savage beauty surrounding me, until the wind buffeted me away from the edge. The sun was sinking, and I beat a reflective retreat to my car. Blown by the wind, now caught under one of my car’s tires was a crumpled Badlands brochure.

While my GPS calculated my route back to the reservation, I flipped through the brochure, with its colorful photographs of narrow-leaf yucca, prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets. My eyes settled on a quote, attributed to author Kathleen Norris:

“The prairie is not forgiving. Anything that is shallow — the easy optimism of the homesteader… the trees whose roots don’t reach ground water — will dry up and blow away.”

The trip left me feeling empowered, eager and unafraid for what might come. That night, safely ensconced in my school-issued housing, I emailed my principal. “I feel very grateful and blessed to have this job,” I wrote. “I would like to stay for a third year as the middle school writing teacher, if you think I am doing a satisfactory job.”

I looked at what I had written, felt a trill of fear in my heart, and hit “Send.”

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the May/June 2019 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments