The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

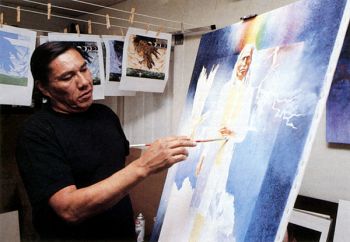

Oscar Howe’s Protégé

Editor’s Note: Bobby Penn, a student of Oscar Howe, was among the foremost Native American artists of the late 20th century. He was a master of oil and acrylic painting, drawing and printmaking. His subjects focused primarily on Indian themes and his own life story. Penn died Feb. 7, 1999, after a long battle with lung problems. His work is included in public collections at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the Vincent Price Gallery in Chicago. Some of Penn's artwork is available through the Akta Lakota Museum online gallery. This story is revised from the July/August 1991 issue of South Dakota Magazine.

From its perch above a southern window in a century-old Clay County farmhouse, a stuffed crow watches Bob Penn paint South Dakota landscapes and Native American symbolisms. Outdoors, a pair of red-tail hawks flies above the hilly grasslands. Just a few country miles away is the University of South Dakota in Vermillion, where Penn studied under Oscar Howe, the master of Sioux art.

Penn, a 44-year-old Sicangu Sioux/Omaha, is rising to the top of his field and is currently doing some of his most bold and striking work. Penn paintings hang in permanent collections at the Smithsonian and the Vincent Price Gallery in Chicago, as well as a dozen regional galleries on the Northern Plains. He has been the focus of 16 one-man shows, including exhibits at the Dahl Fine Arts Center in Rapid City and the Two Rivers Gallery in Minneapolis. Next year, he will share the spotlight with two Oglala Sioux artists, Richard Red Owl and Arthur Amiotte, at an exhibit of Plains Indian Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Fine Art. A new mural commissioned by the Hennepin County (Minneapolis) Medical Center and the mounting of a traveling retrospective occupy his current studio time.

He served as chairman of the art department of Sinte Gleska College in Mission for three years, and has also taught at three other institutions. Early this summer he taught the Oscar Howe Native American Art Institute at the University of South Dakota, an honor Penn particularly cherished. The workshop had been discontinued since Howe's death in 1983. Penn originals can sell for many thousands of dollars, and thanks to his partner/wife Alta, many of his works are now marketed as prints.

He never imagined such success when growing up on the Winnebago Sioux Reservation in Nebraska. At the age of 8, he was placed in an orphanage. In the summer, the school closed and students were sent to foster homes.

Bob learned about farming, carpentry and machinery in boyhood summers. He also joined the orphanage boxing team and for two years was the national champion in his weight class. Every boxer on the orphanage team, in fact, placed as either the national champ or the runner-up.

Looking back, he attributes such success to the fact that other fighters cannot "psyche out" an Indian. Bob's father was a professional boxer and Bob thought about going to the Olympics or turning pro. Instead, he turned to the other love of his life — painting.

Ironically, it was the second time art triumphed over combat for Penn. His first art lesson occurred when his father separated him from a fight with his brother, sat him down and drew an Indian chief's head. "Sit here until you can do that," he commanded. Bob was fascinated ... and hooked on art.

He attended St. Francis Indian School on the Rosebud Reservation and then enrolled at USD in Vermillion and experienced "super shock." It was the first time he felt the pains of prejudice. But it was also the place he met Oscar Howe, the Yanktonai Sioux from the Crow Creek Reservation who became South Dakota Artist Laureate and was recognized worldwide as the leading painter of Sioux art.

Howe rigorously fought the categorization of Indian art. In 1958, the curator of the Philbrook Art Center in Tulsa refused one of Oscar's works because it didn't fit the "Indian style." In an indignant reply, Howe wrote: "Who ever said that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian art than pretty, stylized pictures. ... Every bit in my paintings is a true studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with individualism, dictated to, as the Indian always has been, put on reservations and treated like a child ... ?

"Well, I am not going to stand for it," continued Howe's letter. "Indian art can compete with any art ... I only hope the art world will not be one more contributor to holding us in chains."

Howe's letter cast off restrictions that had bound Indian artists for years at the Oklahoma exhibit. Indian painters deluged the competition with new and innovative styles of work.

It was in this atmosphere of new artistic freedom that Bob Penn began his instruction under Howe. For five years, the two worked together, often one-on-one, and Penn recalls these years as the most significant period of his life. Howe termed Penn his most talented student.

However, talent and hard work don't always mean immediate success in the art world. Penn has paid his dues. He played in several rhythm and blues bands and worked as an artist for both the USD School of Medicine and USD Educational Media Services. Though much of the work involved graphic layout, signs and posters, he learned technique and self-discipline. Between jobs he traveled to show his art, and slowly his paintings gained popularity.

His career also was boosted by romance. He met his wife, Alta, when she was an art gallery curator in Sedona, Arizona. She is an artist in her own right, but she is also adept at business and handles most of the family financial arrangements. She spirits Bob's works from the studio as soon as he finishes. "Otherwise," she says, ''I'm likely to come downstairs and find that he's done a touch-up, and covered a perfectly good painting completely with an entirely new one!"

They enjoy Clay County living. The hawks who patrol the river valley seem to welcome the Penns, and Bob and Alta persuaded their landlord to preserve the prairie grassland pasture which cascades southward from their front porch to the Vermillion River.

Vermillion, despite those first awkward years in the 1960s, has been good to Bob Penn. The university commissioned him to create a mural for the Lakota cafeteria in 1989. It is a traditional Sioux design Penn had contemplated for years, saving for just the right location. The pattern — narrow horizontal bands of color which represent the four directional winds, struck through with yellow (lightning) and anchored by a shield — wishes visitors a long and fruitful life.

W.H. Over Museum in Vermillion also commissioned a piece that Penn calls "in the Charles Russell style." The museum is building a room to showcase the painting.

Penn has not yet seen the movie Dances With Wolves but says he was glad to hear it is not just another movie where the white super-hero comes along and saves the Indian. "I understand that (Costner as) Lt. Dunbar is respectful and inquisitive, willing to let the world be what it should be."

Penn added, "I try to approach my art the same way. To be prejudiced closes so many doors to things you can learn."

A look around his workshop makes it obvious that Penn, like his mentor Howe, is stretching the limits of what might be considered traditional. Abstracts, still lifes and unusual landscapes are on canvasses. With a smile, he notes that anything he does is Indian art solely because he is Indian.

"The important thing is not to draw limits for myself, but to continue exploring new media and styles," he says. "If a brush stroke doesn't give me the effect I'm seeking, I may go into the yard for a misshapen twig. Art is what forces me to grow ... my desire is just so strong."

The crow watches, always, from his roost by the farmhouse window. And the crow often appears in his works. Penn calls it his personal totem.

"Birds were important to the Indian," he explained. "They could fly higher, carry the prayers closer to God. I chose the crow because of its cunning, its adaptability, and ability to survive. The crow is the organic shape of many of my works that balances the harder edges. For a good painting I try to find a balance; I try to live my life the same way."

Rick Geyerman, of Mitchell, was a classmate of Bob Penn at USD in the 1960s. One of his avocations is freelance writing.

Comments

am sure would be interesting.