The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Animal Wisdom Stories

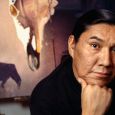

Mark McGinnis has a reputation as an artist who isn't afraid to mix politics and paint. Nuclear weapons, socialism vs. capitalism and foreign policy are issues he has dealt with throughout his career.

So you can understand his friends' surprise when he started a series on animals — buffalo, coyotes, mice, frogs and the like.

It developed almost by chance. In 1991, McGinnis was finishing a series on explorers. As usual, he found a controversial angle. He was comparing the explorers' textbook reputations with his own expression of their lives based on historical research.

"One of the paintings was of Balboa and his dog, Leoncico," says McGinnis. "To my surprise, I found painting the dog to be very enjoyable. I had never painted animals before."

A year later, contemplating his next series and weary of confrontational art, he remembered the enjoyment of doing the dog and decided to create a series of animals based on Greek fables.

He soon changed the focus from Greek to Lakota/Dakota. "I thought it would be foolish to do a series on Greek fables when I was sitting in a homeland rich in animal stories of our own."

As with all his projects, McGinnis began with extensive research. He studied Native American animal legends in turn-of-the-century books about Indian life.

At the same time, he became active in the South Dakota Peace and Justice Center and agreed to interview members of the Lakota and Dakota tribes for a newspaper project. He met many people on the reservations who knew similar animal stories. He also developed an even greater admiration for the Native American culture. "The people I interviewed really opened my eyes to the wonderful diversity of the Indian people and the wisdom that is there."

When he visited with Indians about the animal stories, he found many knew the tales. "Sometimes they had a slightly different version, but I was amazed at how many had heard the stories before."

Although Indian literature has historically been passed on orally rather than in written form, McGinnis says it has been preserved, and his goal is not to educate Indians about Indian stories. "This project is structured primarily for the European-American audience. I hope it gets some exposure to the Native Americans in the state, but I don't think of myself in any way as a person who is going to teach them about their culture."

Though McGinnis' previous artistic subjects seemed foreign to South Dakota, he is not. Born and raised in Aberdeen, the son of a Milwaukee Railroad worker, he studied art at Northern State College. He received a master’s of fine arts degree from the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana and was working for an Indianapolis art gallery when Northern State offered him a teaching position in 1976.

He came home and taught art for 30 years. McGinnis is now retired from teaching but he’s still making art, specializing in acrylic, black ink and watercolor in Boise, Idaho.

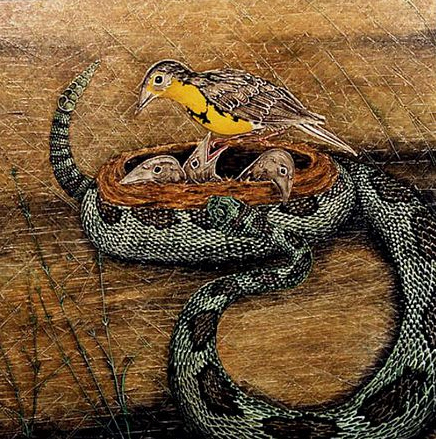

The Meadowlark and the Rattlesnake

|

Once upon a time, there was a mother meadowlark. She had some little baby birds, but they weren’t quite ready to fly yet.

While she was sitting there with her little ones, a big rattlesnake came and coiled around her nest. She was very frightened. She feared for her little ones. She didn’t quite know what to do. She was shaking. Her heart was beating very fast. She had to think real fast about what to do. So she said, “Oh! Your uncle is here, your uncle almost never comes, finally came today, so I must cook for him!”

She turned to her oldest little one. She said, “Go and borrow a kettle, cause I must cook for your uncle. He must be very hungry. Hurry back with the kettle!”

So she sent the oldest one on. Pretty soon, he didn’t come back for a long time, so the snake waited there and kinda moved around a little bit and squeezed the nest a little bit tighter. And she got scared again so she told the second to the oldest son, she said, “You go find your brother, he must have got lost.”

So the next one [went]. She was just sitting there just talking, trying to keep the snake occupied. She ran out of things to say and the snake got restless because they didn’t come with the kettle. He moved closer and closer and coiled up his head.

She said to the youngest. “Go find your brothers! They should have been back. Maybe they both got lost. Bring the kettle cause your uncle is very hungry. I gonna cook for him,” she said.

So the youngest [ran] out of the nest and left. So now she had all the young ones out of the net, she flapped her wings and she flew up out of the nest as fast as she could. She said, “There, sit there and wait for whoever is going to cook for you.”

— Buckskin Tokens: Contemporary Oral Narratives of the Sioux by R.D. Theisz, editor (1975)

The Eagle and the Beaver

|

Out of the quiet blue sky there shot like an arrow the great War-eagle. Beside the clear brown stream an old Beaver-woman was busily chopping wood. Yet she was not too busy to catch the whir of descending wings, and the Eagle reached too late the spot where she had vanished in the midst of the shining pool

He perched sullenly upon a dead tree nearby and kept his eyes steadily upon the smooth sheet of water above the dam.

After a time the water was gently stirred, and a sleek, brown head cautiously appeared above it.

“What right have you,” reproached the Beaver-woman, “to disturb thus the mother of a peaceful and hard-working people?”

“Ugh, I am hungry,” the Eagle replied shortly.

“Then why not do as we do — let other folks alone and work for a living?”

“That is all very well for you,” the Eagle retorted, “but not everybody can cut down trees with his teeth or live upon bark and weeds in a mud-plastered wigwam. I am a warrior, not an old woman!”

“It is true that some people are born trouble-makers,” returned the Beaver quietly. “Yet I see no good reason why you, as well as we, should not be content with plain fare and willing to toil for what you want. My work, moreover, is of use to others besides myself and my family, for with my dam-building I deepen the stream for the use of all the dwellers therein, while you are a terror to all living creatures that were weaker than yourself. You would do well to profit by my example.”

So saying, she dove down again to the bottom of the pool.

The Eagle waited patiently for a long time, but he saw nothing more of her; and so, in spite of his contempt for the harmless industry of an old Beaver-woman, it was he, not she, who was obliged to go hungry that morning.

— Wigwam Evenings: Sioux Folk Tales Retold by Charles and Elaine Eastman (1909)

The Raccoon and the Crawfish

|

Sharp and cunning is the raccoon, say the Indians, by whom he is named Spotted Face.

A crawfish one evening wandered along a riverbank looking for something dead to feast. A raccoon was also looking for something to eat. He spied the crawfish and formed a plan to catch him.

He lay down on the bank and feigned to be dead. By the by, the crawfish came nearby. “Ho,” he thought, “here is a feast indeed, but is he really dead? I will go near and pinch him with my claws and find out.”

So he went near and pinched the raccoon on the nose and then on his soft paws. The raccoon never moved. The crawfish then pinched him on the ribs and tickled him so the raccoon could hardly keep from laughing. The crawfish at last left him. “The raccoon is surely dead,” he thought. And he hurried back to the crawfish village and reported his find to the chief.

All the villagers were called to go down to the feast. The chief bade the warriors and young men to paint their faces and dress in their gayest for a dance.

So they marched in a long line — first the warriors, with their weapons in hand, then the women with their babies and children — to the place where the raccoon lay. They formed a great circle about him and danced, singing:

We shall have a great feast

On the spotted-face beast, with the soft smooth paws:

He is dead!

He is dead!

We shall dance!

We shall have a good time

We shall feast on his flesh.

But as they danced, the raccoon suddenly sprang to his feet.

“Who is that you say you are going to eat? He has a spotted face, has he? He has soft paws, has he? I’ll break your ugly backs. I’ll break your rough bones. I’ll crunch your ugly, rough paws.” And he rushed among the crawfish, killing them by the scores. The crawfish warriors fought bravely and the women ran screaming, all to no purpose. They did not feast on the raccoon; the raccoon feasted on them!

— Myths and Legends of the Sioux by Marie McLaughlin (1916)

The Little Mice

|

Once upon a time, a prairie mouse busied herself all fall storing away a cache of beans. Every morning she was out early with her empty cast-off snakeskin, which she filled with ground beans and dragged home with her teeth.

The little mouse had a cousin who was fond of dancing and talk but who did not like to work. She was not careful to get her cache of beans, and the season was already well gone before she thought to bestir herself. When she came to realize her need she found she had no packing bag, so she went to her hardworking cousin and said, “Cousin, I have no beans stored for the winter, and the season is nearly gone. But I have no snakeskin to gather the beans in. Will you lend me one?”

“But why have you no packing bag? Where were you in the moon when the snakes cast off their skins?”

“I was here.”

“What were you doing?”

“I was busy talking and dancing.”

“And now you are punished,” said the other. “It is always so with lazy careless people. But I will let you have the snakeskin. And now go, and by hard work and industry try to recover your wasted time.”

— Myths and Legends of the Sioux by Marie McLaughlin (1916)

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the September/October 1993 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments