The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Forgotten Giant

|

| Mike McHugh hoped Northern State University could preserve Lincoln Hall, named for Isaac Lincoln, his step-grandfather and a founder of the university. Sadly, the building was demolished in June 2024. |

Editor’s Note: Demolition crews in Aberdeen tore down Lincoln Hall on the Northern State University campus in June. This story, revised from the November/December 2022 issue of South Dakota Magazine, tells the story of its namesake, Isaac Lincoln. To order or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Mike McHugh sadly tore down the grain elevator on his Brown County farm a year ago. Built by his step-grandfather, the elevator was a local landmark for more than a century. As a teenager in the 1960s, McHugh unloaded grain there. A horse-and-buggy-days structure, even 60 years ago it had been too small for the trucks, but McHugh kept it long after it was useful.

He had that same sad feeling a few months earlier when he learned the fate of Lincoln Hall at Northern State University, 12 miles away in Aberdeen. NSU planned to demolish and replace the 1918 building after, like McHugh’s elevator, it had outlived its usefulness. Over the years, Aberdonians and Northern alums came to assume Lincoln Hall — originally built as a women’s dormitory — had been named in tribute to our 16th president, Abraham Lincoln. But it was not, and that was the source of McHugh’s sorrow. Lincoln Hall honors Isaac Lincoln, a forgotten giant in Aberdeen and Northern State history — and McHugh’s step-grandfather, the same man who built the family grain elevator.

*****

Isaac Lincoln was born to a pedigreed New England family in 1863. His mother’s brothers served in Congress and in President Lincoln’s cabinet. Isaac Lincoln himself may have been distantly related to the president on his father’s side, but his destiny lay far from Washington. He developed wanderlust as a young man, moving first to Indiana, then Dakota Territory to work on farms.

|

| Isaac Lincoln. |

He arrived in Aberdeen in 1886 and made his mark in real estate and banking, eventually serving as an officer or director for several banks in Aberdeen, northeastern South Dakota and Minneapolis. In 1903, he bought 1,760 acres on the Elm River near Aberdeen and became a model farmer, known for sharing his knowledge with neighbors and students. He proudly loaded his livestock on a boxcar in nearby Ordway and showed them as far away as Chicago. The animals, especially his prized Galloway cattle, frequently won top honors. “He would paint the inside of his barn bright white to show off the cattle’s rich black coat,” McHugh says.

After a 1913 fire, he built a “palatial farm residence and a monster grain elevator,” according to one local newspaper report. Later that year, another fire destroyed a barn, and Lincoln built “one of the finest barns in the county.” The barn and house (a fire survivor) still stand. The “monster” elevator was the structure that McHugh sadly demolished in 2021.

The farm came to be known as Lincoln Ranch, the name McHugh still uses a century after Lincoln died. It became McHugh’s thanks to Lincoln’s 1906 marriage at age 43 to Margaret Ringrose McHugh, the 48-year-old proprietor of the Sherman Department Store. Arriving in Aberdeen in 1883, she married P.J. McHugh and they moved to Minnesota. After McHugh’s 1889 death, she returned to Aberdeen in 1893 with sons Phil and Frank, who became Mike’s father.

*****

Along with state senator James Lawson and Father Robert Haire, Lincoln is credited as a founder of Northern State University. On the committee to help select its location, Lincoln gave a tour of options to Gov. Andrew Lee, who chose the south end of town for the new Northern Normal and Industrial School.

In 1901, the Board of Regents appointed Lincoln its local secretary, “an entirely honorary position” with “no pay,” a paper reported. Doing much more than verify bills, Lincoln helped oversee the institution’s development, including the construction of its first building — even through disaster.

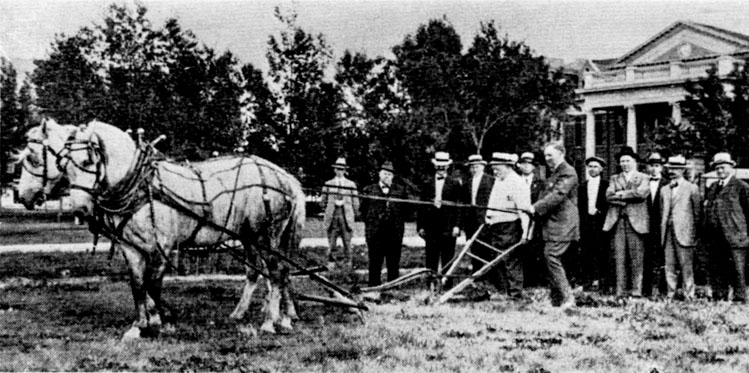

|

| In the summer of 1917, Isaac Lincoln used a horse-drawn plow to break ground for the building that was to bear his name. |

In late December 1901, young Phil McHugh, Lincoln’s future stepson, discovered the blaze on his way to skate on Moccasin Creek. When the fire department arrived, however, the building was beyond saving. As one man walked up Jay Street to view the flames, he found Lincoln.

“Well, Lincoln,” he said, “I suppose this ends our Normal School idea.”

“Hell, no,” Lincoln replied. “We have just commenced to fight.”

The building was rebuilt, and NNIS opened in September 1902.

Lincoln oversaw construction of a new women’s dormitory in 1904, a workshop to implement the “industrial” aspect of the new college’s name, and created an oratory contest that outlived him.

Perhaps inspired by his uncles’ public service, Lincoln sought and won election to the state senate in 1906. During his first term, he spearheaded a $60,000 bill for a new building at Northern. At its dedication, the senate appropriations chair credited Lincoln with securing a larger appropriation for Northern than the other state colleges received. “If the other schools had had a Mr. Lincoln in the senate they might have obtained more money,” the senator noted. After a reelection defeat in 1908, Lincoln returned to the senate in 1914 and served until his death in 1921.

In a posthumous postscript to Lincoln’s NSU and public service careers, his stepson, Democratic Sen. Frank McHugh, introduced the 1939 bill that changed NNIS’ name to Northern State Teachers College, a longtime Northern goal. About seven decades later, Mike McHugh, also a Democrat, ran unsuccessfully for the state legislature. Both men were also involved in many community service and nonprofit activities, inspired, McHugh believes, by Lincoln’s public-spiritedness.

*****

Lincoln resigned as Northern’s secretary in 1909. In 1917, the legislature approved construction of a women’s dorm, and the Regents named it after Lincoln to honor his long dedication to the school. A local paper was effusive: “When finished the new hall will probably be the finest, largest and most thoroly [sic] equipped dormitory in the two Dakotas.” It went on to make the same case that McHugh would champion a century later: “Mr. Lincoln has been largely instrumental in making the school what it is today, and it owes its success in a great measure to him.”

To kick off construction, the honoree and part-time farmer drove two horses pulling a plow to break ground at the site in the summer of 1917. Lincoln Hall opened in October 1918 during a World War and a worldwide pandemic. Since then, the versatile building has been enlarged and has housed students as well as an art gallery, the business school and international programs.

Just three years later, at age 58, Lincoln died of stomach cancer. Obituaries struggled to describe the man’s breadth. “It is a question whether Senator Lincoln was better known as a financier or as a farmer,” one tribute read. “His life has left its imprint on South Dakota development in both lines of activity.” Many businesses closed on the day of his funeral, and 1,000 people passed through his Aberdeen home to pay respects.

*****

When Neal Schnoor became NSU president in July 2021, he inherited the Lincoln Hall project. The original plan was to put the business school, the SDSU accelerated nursing program, an entrepreneurship center and the admissions office in a renovated Lincoln Hall. However, Schnoor said, “We encountered many obstacles in accessibility, technology — it still has the original 1917 wiring — and design. Contractors told us that renovating the building would double the $29.5 million project cost,” and it would still be a rehabbed dormitory, not a modern instructional and community engagement space. Plans shifted, and in one of those coincidences of history the demolition of Lincoln Hall was announced in the centenary year of its namesake’s death.

|

| Lincoln Hall, photographed in 2022, was originally built as a women's dormitory but also housed an art gallery, the business school and international programs. |

Having faced similar issues with several buildings on Lincoln Ranch — including the “monster” elevator — McHugh understood the quandary, but he went to bat for his step-grandfather. “Had there not been an Isaac Lincoln, I don’t know what Northern would be today,” he says. “I’m not diminishing other contributions, but Lincoln had a very important impact on the early formative years of the institution.” Perhaps following his step-grandfather’s determination, he had just commenced to fight.

Hoping to preserve the name on the new building, McHugh spoke at events in Aberdeen and visited with legislators, Regents, NSU staff and Schnoor himself. “Mike is highlighting the achievements of a remarkable man and doing that highlights the supportive community that got Northern built,” Schnoor says.

While McHugh’s conversations were happening, NSU supporters successfully lobbied legislators to support a $29.5 million appropriation of American Rescue Plan Act funds for the project. Senate Bill 44, the title of which read in part “construction of the new Lincoln Hall,” passed both houses and was signed by the governor in March 2022.

Despite the bill’s title, Schnoor told McHugh that typically a building’s name continues only for its useful life. He added, however, “I have a plan for naming our most prominent enduring campus feature for Isaac Lincoln in perpetuity. I’m not saying that to appease anyone. History matters to us.”

Buildings might outlast their usefulness, but people don’t, even a century or more after they’re gone. McHugh’s campaign to preserve Isaac Lincoln’s name has brought his contributions back to light, and he has found allies in Schnoor, the NSU community and Aberdeen. Lincoln fought tirelessly for his town and school, and he’d be proud to know his grandson is fighting for him.

Comments