The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Goat Watcher

|

| A ragtag herd of mountain goats has chosen to live on the high cliffs of Spearfish Canyon. |

Mountain goats have a reputation as escape artists, so it wasn’t a shock when a nanny left Custer State Park in 2016 and showed up about 70 miles away in Spearfish Canyon. The bigger surprise is that there are now 10 goats in the canyon, leaving wildlife officials to wonder what comes next.

Les Heiserman, a retired Spearfish school custodian and inveterate explorer of the canyon, was one of the first persons to observe the nanny. “I first saw her in 2016,” says Heiserman, who visits the canyon daily. “We know she came from Custer State Park because they put a radio collar on her there, but no one had any idea she would travel so far away.”

He has been watching, photographing and advocating for the stray goats ever since. A billy showed up in 2017, and a kid was born the following spring. With so many goats to watch, Heiserman began to name them just so he could keep track. He called the matriarch Granny Nanny. The billy is Bill. Other names include Thimbleberry, Broken Horn, Scooter, Rocky and No. 18 (because he was the first kid, born in 2018).

“I name them for their physical characteristics for the most part,” he says. Thimbleberry was an exception; that name came from seeing the young goat chewing on the fruit of a thimbleberry bush.

|

| The wooly, snow-white creatures are native to the northern Rockies and Canada. Though misidentified as goats by early explorers, they are more closely related to the gazelles and antelopes of Africa. |

Despite the namings and his frequent visits, Heiserman keeps a distance from the goats because he worries that too much familiarity with humans could put them at risk. “They don’t mind me, but I know they will shy away from strangers.”

Though the goats generally dwell atop the rocky, rugged limestone cliffs of the 1,000-foot-deep gorge, they sometimes descend to the scenic byway, Highway 14A, that winds 22 miles through the canyon floor. “They love it behind Bridal Veil Falls,” Heiserman says. “They also like to splash in Spearfish Creek and jump over the fallen logs or pose in the stream.”

Tens of thousands of cars, campers and logging trucks travel the byway. Even though the speed limit is 35 miles per hour, Heiserman is concerned that the goats are at risk. “Goats can get salt starved,” he says. “It’s possible that they come down to lick salt off the road, especially in winter. They probably also come down to drink from the creek.”

Because tourists, and even many locals, are not aware that goats are in the vicinity, Heiserman embarked on a campaign to post warning signs. He is adept at climbing the canyon walls, even with a camera around his neck; as it turns out, he’s equally skilled at maneuvering the bureaucracy of government.

Numerous state and federal departments share responsibilities in the canyon, so it was complicated to get everyone to agree on what to do and how to do it. Finally, the state highway department acted on a recommendation from the state Game, Fish and Parks Department — with approval from the U.S. Forest Service — to post the cautionary road signs.

Heiserman says another danger for the goats is inbreeding. Thus far, the entire herd has descended from Granny Nanny and Bill. “They could use a fresh gene pool here,” he says, meaning the introduction of another billy goat.

They face a more immediate threat atop the canyon, not from humans, genetics or vehicles but rather from mountain lions. Chad Lehman, a senior wildlife biologist for the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks, says lion predation can affect goat populations.

“We just did a survey and we counted 49 mountain goats in the Custer State Park area, which is down quite a bit,” Lehman says. “The last time we did a survey was in 2018 and then we estimated about 130. We never have an exact count, and we don’t have enough collared goats to know for sure, but there are fewer of them, and we will probably recommend closing the mountain goat hunting season next year.”

Mountain goats are not native to the Black Hills. Their original and natural habitat is Alaska, Canada and the northern Rocky Mountains. They are considered an invasive species in other places. Fifty goats were shot last year in Grand Teton National Park, where officials are hoping for a full extermination. Authorities there think they hinder native flora and fauna, including the bighorn sheep.

|

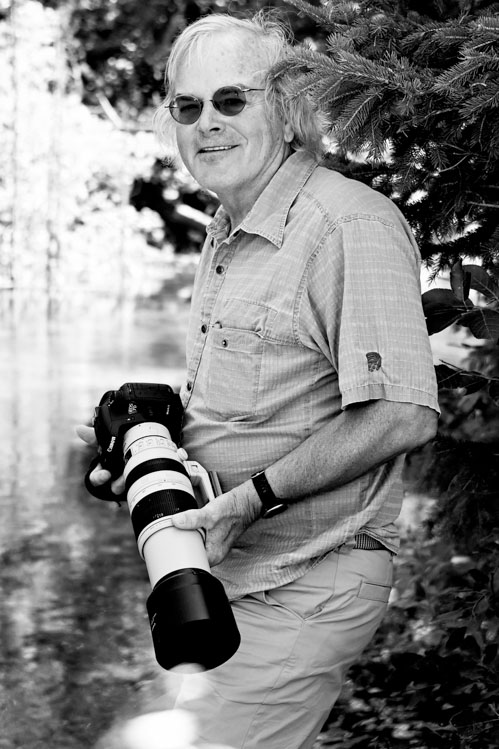

| Few people know Spearfish Canyon like Les Heiserman. Wildlife officials call him a citizen scientist. |

“It’s interesting how two national parks deal with the same critter so differently,” Heiserman says. “In Montana’s Glacier National Park, the goats are revered, almost like the sacred cows of India.”

Lehman and other wildlife officials in South Dakota say they are not concerned about the goats’ environmental impact, and they have nearly a century of experience on the matter. The first goats came to South Dakota in 1924 when Custer State Park, then in its infancy, featured a zoo that provided visitors a close-up view of bear, deer, elk and other species.

Six goats were brought to the zoo from Alberta, Canada, but two escaped the fenced enclosure on their first night in the Hills, and within a few years the entire herd was living on the Black Elk Peak range. Their numbers grew to a high of 400 in the 1940s, and occasionally a billy or nanny has ventured away from the park.

“They need precipitous terrain,” Lehman says. “They love places that are really steep. The granite outcroppings in Custer State Park, the Needles Eye and the Black Elk Wilderness Area all have incredibly steep, granite cliffs. We’ve also had a bunch move into Battle Creek Canyon to the east where it’s basically just a sheer cliff. We had one nanny go to the Boy Scout Camp area on a limestone plateau where she lived for eight years all on her own. We had another in the Bethlehem Cave area for a couple of years, so we’ve got these bizarre stories of how they’ve traveled.”

Lehman says it’s difficult for Game, Fish and Parks staff to monitor the well-being of the wide-ranging goats, so he appreciates “citizen scientists” like Heiserman who monitor and advocate for them.

“I know that Les pretty much lives in the canyon, and he does it just right. You want to be there, yet not too close. What can happen if you habituate them is that they might suddenly inflict their dominance — maybe not on you but on another unsuspecting tourist who gets too close.”

Heiserman does get close enough to document the canyon herd throughout the four seasons. Using a Canon camera with a 100/400 lens, the talented, self-taught photographer captures excellent pictures of the goats and other scenery in the canyon. He posts photos and occasional videos almost daily on his Facebook page, which is open to the public and has a big following. He even published a 2023 goat calendar, which is available through his Facebook page.

|

| Visitors to the canyon are attracted to the goats' playful nature. Though seemingly tame, wildlife officials caution that they are wild animals and can be dangerous. |

Heiserman also shares other tips on enjoying Spearfish Canyon. He has photographed and written about the rare American Dipper as well as osprey, eagles and numerous other species. “The more I know about Spearfish Canyon, the more I realize I don’t know,” he says. “There are subtle changes in the flora and fauna. I recently spotted a peregrine falcon, and then while in the canyon I met an experienced falconer who explained some of the sounds they were making. He thought they were fledglings crying out for food.”

He’s intrigued by the mining and logging activity, the pioneer history and the geology of the canyon. However, the mountain goats get most of his attention. In early summer he saw the kids playing a version of “king of the mountain” on a granite promontory. He’s watched as the nannies teach their young how to make the most of the gifts Mother Nature gave them — their cloven hooves and their horns.

The two-toed hooves expand widely to give them greater balance, and the rough pads of each toe give them a firm grip. That allows them to scale and traverse steep cliffs and walls that scare even mountain lions. But there’s also a technique involved. The goats learn to scratch away loose rocks. They learn to look before they leap. They experiment on how to use speed for horizontal jumps.

Those death-defying theatrics and more show up on Heiserman’s Facebook page. It’s also where followers learned, in April of 2022, that Granny Nanny had died. “When I first saw her, she was a strong-looking goat, but when she passed away, she was worn down to nothing and her teeth were gone.”

That same spring brought the birth of two kids, however, so Granny’s little tribe continues to prosper. Watch for them if you drive through the canyon and follow their growth on Heiserman’s social media postings.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2023 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments