The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

West River Melting Pot

Jul 28, 2015

|

We really have a thing for rocks at South Dakota Magazine. I’m not ready to call it an unnatural obsession because rocks really can be quite fascinating. And they are natural, so I guess it would be natural obsession?

Anyway, two weeks ago in our online feature on Moody County, we wrote about Lone Rock, a huge glacial erratic and local landmark. Lone Rock had been our selection back in the summer of 2011, when the magazine did a feature on one unusual thing to see in every county.

When it came to Haakon County, guess what we chose? Yep. More rocks. This time a pile of them. But just like Lone Rock, there’s a story behind the stack that helps us understand the uncertainty that came with settling Haakon County, a 1,800-square-mile tract right in the middle of West River whose untamed prairie could easily have intimidated homesteaders as they eventually trickled across the Missouri River.

This manmade landmark is the Silent Guide Monument, built sometime in the late 1800s or early 1900s by a sheepherder who wanted to mark a well that never seemed to go dry. It originally stood 14 feet tall and could be seen from 35 miles around. As cowboys and sheepherders battled for land, cattlemen sometimes roped the monument and pulled the stones to the ground. Once, a fed-up sheep man sat atop the pile with his shotgun, daring others to destroy it.

|

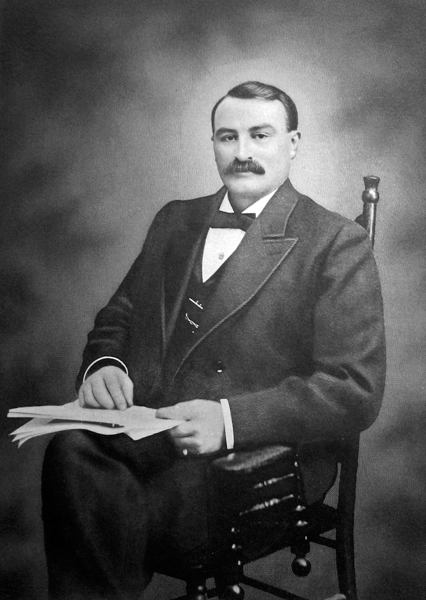

| James "Scotty" Philip. |

The monument’s importance faded as more homesteaders arrived and found their own wells. Still, locals kept watch over it, rebuilding its stones when they naturally toppled to the earth. Eventually they were permanently cemented together. You’ll find the Silent Guide Monument about 8 miles west of Philip on the way to Grindstone.

Many of the early homesteaders who relied on the monument were Scandinavian, which explains why the county was named after King Haakon VII of Norway after its creation in 1914. It’s the only county in South Dakota named for a non-American person, and is one of nine named for people who did not live in South Dakota.

One exception to that immigration rule was James “Scotty” Philip, who came from Scotland in 1874 and settled east of Philip in 1881. Philip is best known as “the man who saved the buffalo,” although history has shown that fellow rancher Fred Dupris deserves just as much credit as Scotty. Still, you can’t think of Philip without thinking of buffalo.

|

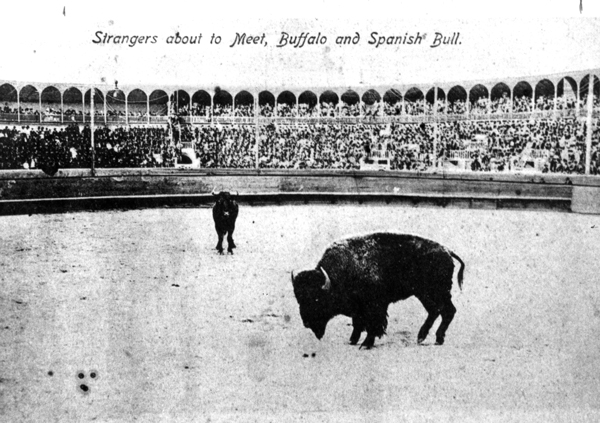

| Scotty Philip's bison were up to the challenge presented by Mexican fighting bulls. |

Our favorite story involving Scotty’s herd happened in 1907, when Philip was on a fall buying trip to Texas. He encountered two men from Juarez, Mexico, who were bragging about the toughness and stamina of their country’s fighting bulls. Philip suggested that any one of his bison could easily take down a bull, and offered to prove it by shipping one or more south for a fight.

Philip selected an 8-year-old named Pierre and a 4-year-old, and under the guidance of his nephew, George, they departed for Juarez. On the day of the fight, Pierre sauntered into the ring and, tired from his long journey, flopped down right in the middle. The crowd roared when the Mexican fighting bull was released. He was eager to fight because darts had been plunged into his shoulder to enhance his spirit.

|

| A favorite hangout for local ranchers is the Philip Livestock Auction Barn. Cattle sales are held on Tuesdays, and the popular cafe is open daily. Gathered (from left) are Jake Schofield, Barry Barber, Boyd Waara and Thor Roseth, the owner and operator. |

Pierre got to his feet in time to absorb the bull’s first charge. When the dust cleared, there stood Pierre, with the dazed bull wondering what had just happened. A couple more charges left the bull shaking in the arena, the crowd showering him with jeers.

The Mexicans, believing this first bout to be a fluke, sent three more bulls to square off against Pierre. Each time the bison stood his ground, and the question of species superiority was settled once and for all.

Philip became a prominent stockman and legislator before he died suddenly in 1911 at the age of 53. It is said that as he was buried in the family cemetery, his buffalo crested a nearby hill to say a final goodbye. His life was the subject of a recent documentary called The Buffalo King, written and produced by Justin Koehler, who grew up near the tiny settlement of Nowlin in Haakon County and named his Colorado-based film company Nowlin Town Productions.

|

| George Stroppel's healing hands still soothe aches and pains in Midland. |

Philip left several lasting legacies, including the buffalo herd at Custer State Park, which descends from his animals. Another is the town of Philip, formed in 1907 and named after him. It’s the largest city in Haakon County, with 762 people, and is definitely a cow town. The Cattle Business Weekly newspaper is published on Center Street and sale days at Philip Livestock Auction are lively. But there are also amenities you won’t find in most towns fewer than 800, including the Gem, the only movie theater between Pierre and Rapid City.

Just up Highway 14 is Midland, a town of 130 people tucked into the hills of the Bad River Valley. Midland has been known for decades for its healing hot springs and the hands of George Stroppel, longtime operator of the Stroppel Hotel. He has sold the business, and its now called the Lava Water Hotel, but he still offers the massages that draw people from hundreds of miles.

|

| Sundays are busy in Milesville, pop. 2. |

If you relish an even slower pace of life, visit tiny Milesville, pop. 2 — Dan and Gayla Piroutek. The postal service no longer delivers mail there, but two churches still hold Sunday services and the town hall hosts birthdays, anniversaries and other special occasions.

Outside of those towns, there’s a lot of open space in Haakon County — and, if you believe in legends, a buried treasure. Ed Sanchez was one of Haakon County’s earliest homesteaders, settling on land near the Grindstone Buttes in 1878. He operated a roadhouse, ran cattle and carried the mail from Grindstone to Pedro. His business ventures must have been lucrative because local legend says that before Sanchez died in 1902, he buried his fortune in fruit jars along Dirty Woman Creek. Buy a shovel at the hardware store in Philip, head west out of town on the Grindstone Road and try your luck. If you unearth any rocks, just pile them up. They won’t look out of place.

Editor’s Note: This is the seventh installment in an ongoing series featuring South Dakota’s 66 counties. Click here for previous articles.

Comments