The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

Old Highway 16

|

| A stretch of Old Highway 16 east of the Black Hills is now Highway 14/16. |

Can you buy the idea that a highway is a community? A long and narrow one-street town that connects places and people, good and bad happenings and a crazy conglomeration of dogs, deer and duck ponds? If a road is a community, then imagine South Dakota’s U.S. Highway 16 in its heyday. Gutzon Borglum was traveling 16 while carving Mount Rushmore. Korczak Ziolkowski helped him for a time before eyeing his own Crazy Horse carving just down the same road. Dorothy and Ted Hustead were nailing wood signs to fence posts, hoping to attract motorists to their Wall drug store. George McGovern was a shy student at Mitchell High School until he discovered a passion for debate, and motored up and down the highway attending tournaments. Sparky Anderson, the Hall of Fame baseball manager, was learning balls and strikes in Bridgewater, where businessmen promoted their stretch of 16 as Cornhusker Highway in honor of the local baseball league.

Russ Madison, one of the founders of modern-day rodeo, trailed wild broncs and bulls up and down 16 when it was dirt and gravel. Earl Brockelsby, a Black Hills kid with a fascination for snakes and reptiles, was pleased to discover that Highway 16 travelers would pull off the road and pay admission to see his collection. Alex Johnson, a railroader from Chicago, came to Rapid City to build a grand hotel for passersby; showing no modesty, he named it The Alex Johnson.

|

All that and a thousand more lesser-known stories along an east-west hodgepodge of dirt and gravel roads linked not only in South Dakota but across five states. The 1,600-mile journey was configured from Detroit to Yellowstone National Park, crossing Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, South Dakota and Wyoming. Highway 16 was a central segment of several routes to the Black Hills and Yellowstone Park called the Black and Yellow Trail. An association formed in Huron in 1919 to promote the corridors, which also included parts of Highways 14 and 20 in South Dakota. Wood fence posts were painted black and yellow every mile or so to reassure tourists that they were still on track.

At first, Highway 16 was nothing more than a dirt trail. Model T wheels dug deep ruts during wet periods. In West River country, perhaps a car or two would pass down the road every hour on summer days — far fewer at night and in winter. At New Underwood, the road veered to either side of a giant cottonwood tree. Further east at Wicksville, W.H. Wolfenberger attracted travelers to his little store by leashing a pet coyote in the front yard. The store shelves were sparsely stocked with candy and staples, but rumors were that Wolfenberger sold moonshine under the counter.

Highway 16 bordered the north edge of Jack Brainard’s family ranch in eastern Pennington County. “We called it the Black and Yellow Trail, and before that they called it the Custer Battlefield Highway,” he says. It was also called “Fourteen” locally, because Highways 16 and 14 merged through much of West River.

Brainard parlayed his Dakota ranch childhood into a distinguished career as a horseman. Now 94 and living in Whitesboro, Texas, he still remembers a particular day when he saw a cloud of dust on the road to Wasta. “Russ Madison was driving his horses to Wasta for a rodeo, and running in the front was the first palomino I ever saw and I thought it was the prettiest horse I ever saw.”

|

| A dinosaur looms over today's Interstate 90 near wall. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism |

The travel industry soon followed in the path of that palomino. Henry Ford’s new Model A debuted in 1928; it and other car models offered more comfortable and dependable transportation. Mount Rushmore was emerging on the mountain west of Rapid City as a new attraction, along with a buffalo herd at Custer State Park. Soon a wave of hotels, restaurants, gas stations and automobile shops were built to serve the motorists.

The federal government helped gravel the route, providing jobs through the Works Progress Administration in the Great Depression of the 1930s. Workers often hauled the gravel by horse and wagon, and emptied the loads by shovel and muscle. One wagonload graveled about three feet of the roadbed.

The 400-mile stretch of Highway 16 in South Dakota connected Sioux Falls and Rapid City, the state’s two largest cities, along with several dozen smaller towns. Highway 16’s original route connected the main streets of most communities. In the 1940s and 1950s, bypasses were built on the edges of the towns, creating a second wave of motel and gas station construction.

A third wave came in the 1970s when Interstate 90 was constructed in a near-parallel route to Highway 16 across South Dakota, but even further from the local communities. Once again, new service stations, hotels, motels, rock shops and eateries were constructed.

Some travelers bemoan Interstate 90 as monotonous and sterile. Every ditch is mowed and every fence is straight. Highway beauty is in the eye of the beholder behind the wheel. Those who see boredom in the standardization of the federal four-lane — and who aren’t in a hurry to cross the state in 6 hours or less — will enjoy a nostalgic journey down the original 16.

|

| Old trucks at Quinn. |

Phil and JoAnn Stark have observed life in “the slow lane” for most of the last 30 years at Cottonwood, where they ran a bar and store called JoAnn’s Trading Post. “People think nobody lives here,” says Phil, “but Philip and Quinn and Wall are all one big community.” And in the summer, motorcyclists and other travelers who like to venture off the interstate become part of the mix. “They liked the sawdust on the floor, or the idea that they could just pitch a tent out back if they wanted,” says Phil. “Sometimes we’d have a dance the Saturday before the (Sturgis) rally, and the music would just keep going until morning and I don’t remember anyone ever getting in a fight. The people who like the two-lane are peaceful folks who just aren’t in a big hurry.”

South Dakota’s biggest car nut agrees. “People who like the back roads are our kind of people,” says Dave Geisler of the Pioneer Auto Show in Murdo, a sprawling indoor/outdoor museum of collectible cars, motorcycles, tractors, toys and Western memorabilia.

Geisler says Murdo changed with each of the three highway waves. “The old Highway 16 ran right into downtown on Second Street,” he says, on a tour of the town. “Here was a Mobil station. There was the Red Top Cabins. This was Young’s Cabin Park. That was a gas station. Here was Weber’s Deluxe Cabin Court. There was a Skelly’s station. Gas was 25 cents a gallon. Up here was the Conoco station. Nobody could have made much money but they all got along.”

Plenty of daring thinkers and doers populated the Highway 16 community in the middle of the 20th century. Many of their dreams remain intact at Wall Drug, Al’s Oasis, the Murdo auto museum and other lesser-known places. New promoters are also showing up. At the Community Pharmacy in Presho, a small sign boasts of the “Best Coffee Between Sioux Falls and Rapid City.” Further east at Kimball, Keke Leiferman remodeled an old Highway 16 gas station into an eatery and entertainment spot called The Back Forty. “I look at Interstate 90 as my community,” she admits. But the shop sits a half-mile from I-90 on Old 16.

If roads are communities, then I-90 is Sioux Falls on wheels — smooth and speedy — while Old Highway 16 is New Underwood without the cottonwood tree.

Most of Old 16 is still intact and passable. Here’s a guide to the 1950s-era corridor for those who might like to experience the slow lane for at least one nostalgic trip across South Dakota.

Minnesota Border to Bridgewater

|

| Doug and Brenda Deffenbaugh run a honey stand on the honor system near Wall Lake. Brenda (pictured with her son, Drayden) says customers are almost always honest. |

Old 16 enters South Dakota from Minnesota on 262nd Street, which skirts Valley Springs and the south side of Brandon. Just south of Brandon, take a right turn on Madison Street and enter Sioux Falls. Take a left on Sycamore, then a right onto 10th Street and follow it past the backside of Michelangelo’s David statue. The road runs through the heart of Sioux Falls, exiting the city as Hwy 42. Wave goodbye to suburbia because you’ll see little of that for the next 350 miles. You’ll drive past Wall Lake, through the East Vermillion River valley and into the heart of East River farming country on your way to Bridgewater, where Sparky Anderson played baseball as a child before becoming the first Major League manager to win a World Series in both leagues.

Bridgewater to Mitchell

|

| Mitchell's Corn Palace is just a few blocks north of Old Highway 16. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism |

Leave Hwy 42 at Bridgewater and drive northeast on SD Hwy 262 to Alexandria, then north on 421st Avenue. Cross I-90 and you’ll come to Hwy 38. Take it west across the Jim River and Firesteel Creek and enter Mitchell. Watch for a big fiberglass Hereford bull, the trademark for Chef Louie’s. Perhaps the oldest steakhouse on the route, it dates to the 1930s. Hwy 38 becomes Havens Avenue through the city. The famous Corn Palace is just a few blocks north.

Mitchell to White Lake

|

| Bob and Edith Zoon are the longtime proprietors of the A-Bar-Z Motel in White Lake. |

Continue on Hwy 38 past Mount Vernon, home of Minnesota Vikings star linebacker Chad Greenway. As you enter Aurora County, Hwy 38 is still posted as Hwy 16 for a stretch. You’ll drive past Gordy’s Campground in Plankinton. See the war memorials indoors and outdoors at the county courthouse. West of Plankinton the roadbed roughens, the shoulder is gravel and you begin to see less cropland and more grass. You’re now driving between the 99th and 100th meridians, a north-south stretch called America’s “middle border” by some agrarian-minded historians who believe the big difference in rainfall amounts east and west of those imaginary lines affected the settlement of the region.

White Lake to Kimball

|

| The Back Forty in Kimball grew from an old gas station. |

The A-Bar-Z Store & Hotel was built in White Lake along U.S. Hwy 16 several years before President Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Construction Act. Thirty years later, Bob and Edith Zoon were “just friends” when they arrived in 1985 from New Jersey to visit relatives. “We came out and fell in love with the area,” explained Bob. And with each other. They took a trip to the Aurora County Courthouse in Plankinton, where Bob asked, “What does it take to get married here?” The sheriff and his secretary served as witnesses. Then they bought the six-room hotel and gas station on Old 16 and renamed it A-Bar-Z.

As you leave White Lake, local Hwy 16 crosses to the south of Ike’s concrete legacy and you find yourself on 252nd Street. About 12 miles later, you approach Kimball and the South Dakota Tractor Museum. You pass by a tiny Frosty King ice cream shack and then, a half-mile west, a funky coffeehouse, restaurant and bar known as The Back Forty, where proprietor Keke Leiferman gives traditional South Dakota sandwiches a gourmet twist. A mile down the road, you drive beneath an underpass and find yourself on the south side of I-90 once again, going west on what’s now called 251st Street.

Kimball to Chamberlain

|

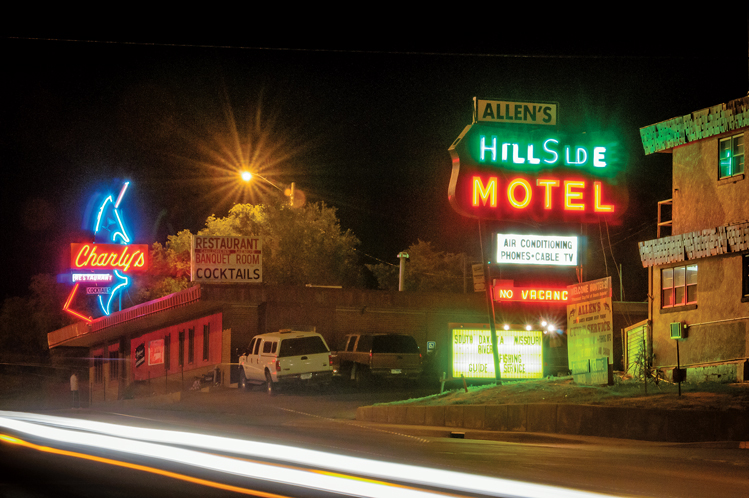

| Hillside Motel in Chamberlain survived the decommissioning of Highway 16. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism |

Eleven miles after leaving Kimball, you pull up to a stop sign for Hwy 50. To the west is a big body of water known as Red Lake. Take Hwy 50 north across I-90 and head for nearby Pukwana, lawn mower racing capital of the Northern Plains. Leave Pukwana on 249th Street going west and you’ll soon rejoin Hwy 50 as it enters Chamberlain, descending into the wide valley of the Missouri River. Spend some time in Chamberlain, a little city with a one-way Main Street that includes a movie theater, restaurants and a bakery called Indulge. Just to the west of Main Street, River Street leads to a shoreline park and walking paths, good opportunities to stretch your legs or enjoy the sweets from the bakery.

Chamberlain to Kennebec

|

| The Lyman County courthouse at Kennebec. |

You’ll cross the Missouri — the USA’s longest river — on an old steel bridge that transformed travel on Hwy 16 when it was finished in September of 1925. The two-way bridge became too narrow for modern cars and trucks. When construction of the Fort Randall Dam expanded the river’s width, an identical bridge at nearby Wheeler was declared surplus and floated upriver. The old bridge became the west lane and the Wheeler bridge is the east lane yet today. Cross the bridge into West River and you’ll drive past Oacoma and Al’s Oasis, a grocery store and highway restaurant made famous by the Mueller family. The old highway ends and you have no choice but to take I-90 for about nine miles, but then you can rejoin Old 16 by turning north on Hwy 47 at Exit 251. Take Hwy 47 northwest into Reliance and then onto Kennebec, where the Lyman County courthouse serves as the bastion of government for 3,700 citizens.

Kennebec to Kadoka

|

| Dave Geisler entertains travelers at the Pioneer Auto Museum in Murdo. |

Now you embark on a long stretch of Old 16 known as Hwy 248 that closely parallels I-90, which is usually within a rifle’s shot. Hwy 248 leads you through eight more little West River towns, in this order: Kennebec, Presho, Vivian, Draper, Murdo, Okaton, Belvidere and Kadoka. Some look like ghost towns at first blush, while others are busier than their modest populations would suggest.

When Highway 16 was in its prime, Keith Patrick’s repair shop at Vivian was a Ford dealership and gas station. Today, pilots occasionally land small planes on the road without fear of hitting a motorist. Patrick fixes anything from cars and tractors to “lawn mowers, vacuum cleaners and eye glasses.” He and his brother, Kevin, display old pictures and memorabilia of Vivian in the shop.

Fading wood gas stations, motels, shops and restaurants are scattered around Draper, pop. 82. Gene Cressy remembers when Highway 16 was constructed in the 1940s, south of the railroad tracks. “The speed limit was 45, 25 on the curves because they were 90-degree curves.” Neighboring schools borrowed the road’s nickname when they organized the Custer Battlefield Conference for sports teams. The conference still exists.

Gurney Seed & Nursery of Yankton started a chain of rural gas stations in the 1930s. Vivian’s station is preserved at Pioneer Auto Museum in Murdo. Dave Geisler has an eclectic collection of 275 old automobiles (including the Dukes of Hazzard’s General Lee) and 30 buildings stocked with Old West and pioneer memorabilia. It grew from a Highway 16 gas station and Chevy dealership started by Dave’s father in the early 1950s.

Check out the dollar bills pinned all over the Reliance Bar, and the Lyman County Courthouse in Kennebec, built in 1925 when Henry Ford was still making Model Ts. In Presho you drive past a sprawling indoor/outdoor museum and Hutch’s, a restaurant and cafe built in the early 1950s that locals love for the hot beef sandwiches.

Kadoka to Cottonwood

|

| A longhorn cow roams the quiet roadway west of Philip Junction. |

The Kadoka to Wall route is not for everybody, or every car. The Old 16 roadbed is still passable, but at times it becomes a West River back road seldom used even by local ranchers.

The stretch begins nicely. You travel east of Kadoka for 7 miles along the same old Hwy 248 until you reach what’s known as Seven Mile Corner. Then Old 16 runs north (now Highway 73) toward Philip. In a dozen or so miles (before arriving in the city of Philip), you drop into a valley called Philip Junction. Notice a family farm in the valley; the building closest to the highway is landscaped with old auto memorabilia. Turn west on a forgotten road that once was U.S. Highway 16, the grandest route from Detroit to Yellowstone. Today, the little asphalt that remains is cracked and dry. It looks like a road from an apocalypse movie.

The path (now 237th Street) is still marked as a “principal route” on many maps and atlases, but they are mistaken. Ruts and holes make it barely passable on a dry summer’s day, and a bad idea on a wet day. This is Jackson County, population 3,200, one of the poorest places in the United States. Little money is available for road maintenance.

You’ll travel 10 slow miles along 237th Street, mostly past pastures and grasslands. You cross two creeks, one called the South Fork Bad River, which flows northward to the Bad River, which flows into the mighty Missouri at Fort Pierre.

Bridges on the creeks seem scary, but they hold a car.

Cottonwood to Wall

|

| Pavement is gone from the road east of Wall. |

The apocalyptic segment runs onto Hwy 14 just east of the tiny town of Cottonwood. Highways 14 and 16 once joined there and continued together to Rapid City. Enjoy the next 10 miles on the smooth and solid Hwy 14 to Quinn, past Wall Drug signs advertising jackalopes, donuts and a 6-foot rabbit.

At Quinn, you face another test. You can continue along Hwy 14, a newer route for Hwy 16, or you can once again “rough it” on the original roadbed to Wall. To find the old road, drive into Quinn and look just south of the railroad tracks for a road marked as Old Hwy 16 & Quinn Road, and take it west.

At first you’ll be on a dirt path, heading past a cattle ranch. Again, this is only for adventurous souls on dry days. The asphalt has all but disappeared. At times, you’ll be on a one-lane path and at one point you’ll even need to enter the ditch to avoid a washout.

Unlike the first stretch of rough road, which is over-promised on most maps, this brief 5-mile path from Quinn to Wall is not even shown on the official state map. Keep driving west and you’ll be rewarded by a scenic jaunt past some swampy land and small bumps, precursors to the big Badlands to the south. You’ll see gnarled old wood posts along the way, and it takes only a little imagination to picture a young Ted Hustead nailing “Free Ice Water” signs on them to attract Model A drivers to stop at his now-famous Wall Drug Store.

Wall to Wasta

|

| The owner of the old Packard Cafe and Motel in Wasta borrowed the name from the luxurious automobile of the 1930s and '40s. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism |

We would be remiss as travel guides if we didn’t recommend a stop at Wall Drug — still owned and operated by the Hustead family — for a buffalo burger, the crispy-soft chocolate doughnuts, 5-cent coffee and free admission to one of the West’s amazing art collections.

According to legend, Hustead actually traveled to Wasta to get water for his customers. If that story is true, then he surely made the drive by heading west on Fourth Avenue. You can do the same, but then the exact route of Old 16 is a mystery. Most likely, today’s I-90 was built over some of the original roadbed. Our recommendation is to take I-90 to Wasta, but then drive into Wasta, where you’ll easily find traces of Hwy 16 on the north side of town. It soon dead-ends if you turn west, but go east a mile and you’ll be rewarded with a better look at the Cheyenne River valley than I-90 travelers enjoy. Park your car and take pictures of the Old 16 car bridge and the nearby railroad bridge, both still in service.

The nearby town of Owanka died due to lack of water. “If they did find water, it had a high sulfur content and they couldn’t drink it,” says Jack Brainard. “They shipped water in on the train.” The name Wasta came from the Lakota name for the springs, mini wasta, or “water good.” When Highway 16 was routed to the north side of town, hotels and restaurants were opened like the Redwood, where motel scenes for the movie Thunderheart were filmed in 1991.

Wasta to Rapid City

|

| Margaret Larson, Alice Richter, Janice Jensen and Joyce Wolken play cards at BJ's Country Store in New Underwood. |

Return to I-90 and head west for just a few miles, then take Exit 90 and go south on 173rd Avenue to the Wicksville Community Church, where services are held on the second, third and fourth Sundays of every month — leaving travelers to wonder what happens on the first Saturday that carries into Sunday morning? At the church corner, you’ll find an old stretch of the original highway that leads east but dead-ends a mile down the road. Head west and you’ll once again be on Old 16, but it’s diplomatically called Hwy 14/16 these days. The Black Hills are now visible on the horizon, just two towns away.

The first is New Underwood, Margaret Larsen’s home for 86 years. Most mornings she can be found at BJ’s Country Store, playing cards with friends. They cheerfully interrupted the game long enough to share stories. “Before the interstate we had a lot more stores — two grocery stores and a lumberyard,” says Larsen. “We still have plenty of bars.”

The next town is Box Elder, home to Ellsworth Air Force Base and one of the Dakotas’ boomtowns of the last 50 years. Box Elder was a tiny place in the heyday of Old 16, but nearly 10,000 people now live there. Hwy 14/16 skirts an old part of the boomtown and enters Rapid City.

Rapid City to Custer

|

| Buffalo graze west of Custer. |

No longer do you need much guidance, because you’re now driving the lone surviving stretch of U.S. Hwy 16. It starts out in downtown Rapid City as Mount Rushmore Road. You’ll climb out of Rapid City and into the mountains on a highway made to accommodate the two million people per year who visit Mount Rushmore. You drive past the Brockelsby family’s Reptile Gardens, Bear Country USA, Fort Hays Old West Town and numerous other visitor attractions.

You skirt the old mining community of Keystone, which sits at the foot of Mount Rushmore, and then follow the old highway as it cuts right through Hill City. There are many interesting stops in the little town, ranging from the century-old Hill City Cafe that remains as unpretentious as the small town eateries you might have enjoyed 200 miles to the east in farming country to an 1880 excursion train and the popular Prairie Berry Winery.

A dozen miles south, you’ll find the Ziolkowski family’s Crazy Horse mountain carving, and then dip down into the city of Custer. Black Hills Burger & Bun Co. is on the west side of the highway as you arrive downtown, one of 35 restaurants in a city of only 2,000 people.

Custer to the Wyoming Border

|

| Three scenic paths wind through Jewel Cave National Park. |

As the elevation climbs you rise beyond all the manmade accouterments that you’ve enjoyed between Rapid City and Custer. Now it’s just you and the forest and the highway, until you reach Jewel Cave National Monument. Want some strenuous exercise? Two unusual trails descend into Hell’s Canyon. This is a rare opportunity for a wilderness walk into one of the Black Hills’ deepest canyons. You’ll likely see birds and wildlife, and feel blasts of cold air as you poke your head into caves that connect to the 170-mile maze that comprises Jewel Cave.

It’s a short drive down the mountain. You enter private rangeland as you reach Wyoming. There’s no official “Welcome to Wyoming” sign, but the border is just a short distance west of the ruins of an abandoned cowboy bar and cafe. U.S. Hwy 16 continues on to Yellowstone, the original destination when federal road planners created this east-west route nearly a century ago.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the July/August 2015 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

The Days of '76 1966 I-90 was done then as i remember!!???

Highway 12 west river into Montana - that was a drive.where you could think no one else was alive.

Pheasant hunted the ditches along 16 and drag raced Hwy 16, 2 miles west of Plankinton in the 70’s.

Memories (obviously not all fond) of SD Hwy 16.

I realize that many have fond memories of where they grew up, but I'm glad I spent those years where I was. And Jon, I-90 may have been finished West River in the mid '60s, but I'm fairly sure it wasn't open just west of Salem.

certainly donate to this brilliant blog! I suppose for now i'll settle for

bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account.

I look forward to new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group.

Talk soon! credit score ratings chart